How NASA tracks carbon emissions from space to better understand — and deal with — climate change

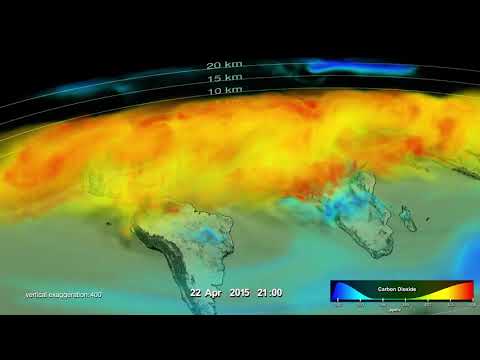

Data from NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2, collected in 2015, show that the springtime terrestrial sink of carbon began in Europe and spread eastward across Asia and North America over the months of May and June.

- Share via

Fires, drought and warmer temperatures were to blame for excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere during the 2015-2016 El Niño, scientists with NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 say.

The findings, part of five papers published in the journal Science, shed light on the mechanisms through which Earth “breathes” carbon dioxide, a potent greenhouse gas, and reveal how those mechanisms affect climate change.

Global temperatures have been on the rise, thanks largely to the human-driven increase in greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide. But not all of the carbon dioxide produced each year ends up in the atmosphere. Some of it gets trapped in the ocean, or locked on land thanks to plants that use the gas during photosynthesis.

“We know how much we’re emitting when we burn fossil fuel, and we see that about half of it stays in the atmosphere and the other half appears to go get absorbed into the land and the ocean,” said Jet Propulsion Laboratory atmospheric scientist Annmarie Eldering, the mission’s deputy project scientist. “But there are still these questions of which parts of the land are doing that.”

And on top of that, the amount that gets pulled out of the atmosphere shifts dramatically from year to year, from about as little as 20% to as much as 80%.

“Why is it that there’s a lot of variability from year to year?” Eldering said. “We didn’t understand why that was.”

Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2, or OCO-2, was launched in July 2014 to help discover those mechanisms and solve that mystery. Because the spacecraft was launched prior to the 2015-2016 El Niño season, it allowed the scientists to get a glimpse of the effect that the weather pattern had on the Earth’s ability to store carbon.

“You can think of it as like a big natural experiment where you had a lot of heat and a lot of drought,” Eldering said. “So we could start investigating, how do plants respond when these conditions happen?”

OCO-2 near-infrared sensors revealed that normal carbon sinks — forests in tropical South America, tropical Africa and Indonesia — weren’t pulling as much carbon down as they had in the past. But they were all doing so for different reasons.

In South America, a long drought was slowing down the growth of trees and other plants, which meant they were taking up carbon dioxide more slowly. In Africa, temperatures were higher, which could mean that dead plant matter was decomposing faster than usual, allowing carbon dioxide to escape. And in Indonesia, a rash of forest and peat fires burned through trees, releasing their stored carbon, while also leaving fewer plants to pull that carbon down.

“Now we can see that the tropical forest and plants didn’t absorb as much carbon as they usually do and that’s what caused this big increase in that time period,” Eldering said.

Altogether, some 3 billion more metric tons of carbon emissions were released from land during El Niño, compared with 2011, the scientists said. And about 80% of those extra emissions came from these three tropical regions.

Drought and higher temperatures have been linked to the climate change fueled by greenhouse gases. Now, it seems that there could be a vicious cycle at work.

“If [the] future climate is more like the climate that we saw during this El Niño, the trouble is that the Earth may actually lose some of the carbon-removal services that we get from these tropical forests, and then CO2 will increase in the atmosphere even faster,” Scott Denning of Colorado State University in Fort Collins, an OCO-2 science team member who was not involved in this research, said at a NASA briefing.

Another paper found that El Niño slightly suppressed the amount of carbon that the ocean released into the atmosphere. If that had not happened, the atmospheric emissions would have been even higher, researchers said.

A third study looked at the carbon emissions of volcanoes and of cities. It found a major carbon spike over populated areas (such as Los Angeles), compared to less-populated regions nearby (such as the deserts to the north).

A fourth paper managed to observe plant activity by looking for photosynthetic fluorescence — the tiny amount of radiation given off by plants as they spin sugar out of sunlight and air.

The final paper, led by Eldering, summarized the state of OCO-2 science.

The results should help experts develop more effective strategies to deal with climate change in the future, Eldering said.

“If you want to make a good plan, you’ve got to have some good information,” she said. “This is going to add to that information, and hopefully be reflected in a better plan down the road.”

The findings come a few months after President Trump’s budget plan proposed to cut OCO-3, a follow-up mission that would continue OCO-2’s work.

Follow @aminawrite on Twitter for more science news and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

Beyond the orbit of Neptune, scientists find a dwarf planet with a ring

MacArthur fellow Emmanuel Candès uses little bits of data to see the big picture

For fighting cybercrime and boosting internet security, UCSD’s Stefan Savage wins a MacArthur award

UPDATES:

4:15 p.m.: The story was updated with details from a NASA briefing.

The article was originally published at 12:40 p.m.