From the dazzling to the disheartening, 2017 was a remarkable year for science

- Share via

For the science fans among us, 2017 was a year of dazzling highs and disheartening lows.

There were thrilling discoveries of planets that might be hospitable to life and major advances in DNA editing that could cure a range of genetic diseases.

We also endured the death of a beloved spacecraft and a series of attacks on the value of scientific research.

Read on to relive a remarkable year in science.

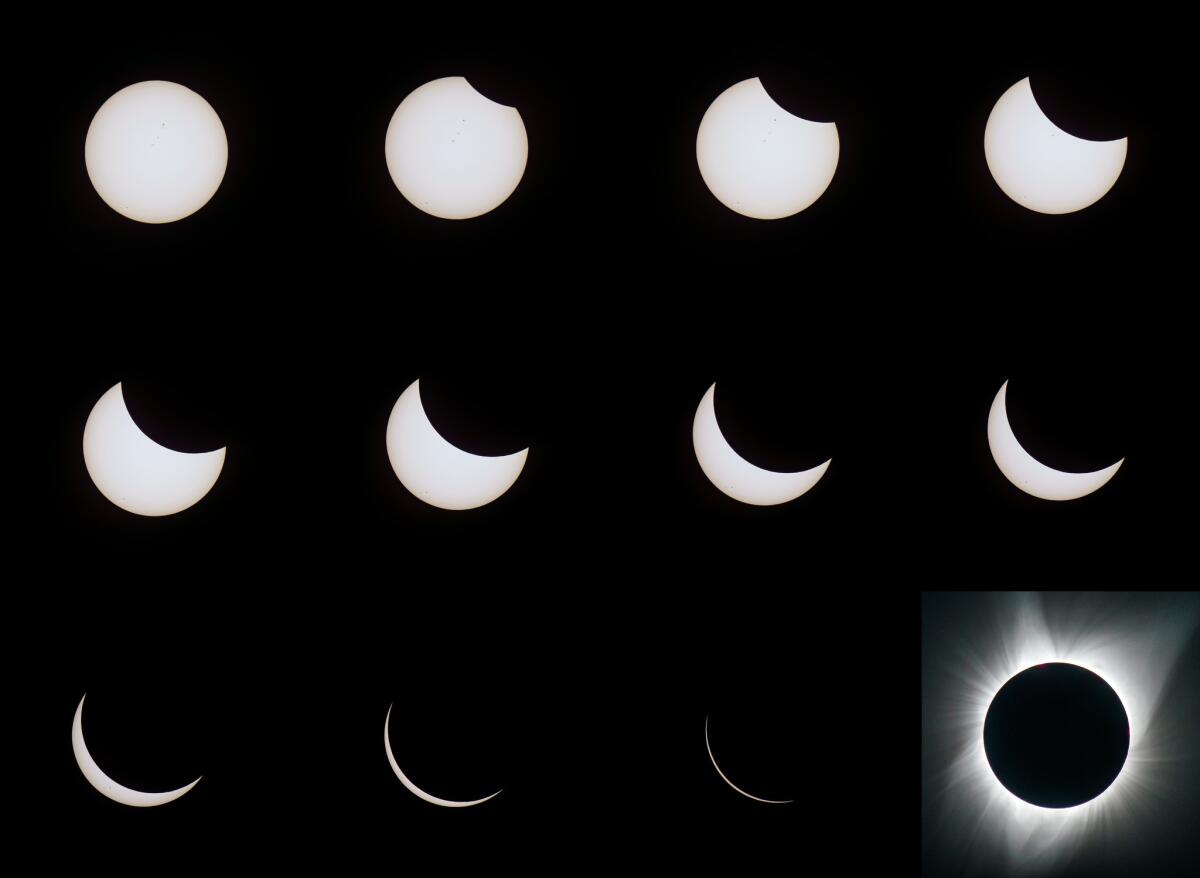

Witnessing the Great American Eclipse

It was a simple quirk of geometry, a perfect alignment of the sun, moon and Earth. On Aug. 21, the Great American Eclipse allowed skywatchers to witness a cosmic hiccup in the usual day-night cycle.

For the first time in nearly a century, a total solar eclipse was visible across North America. Millions turned out along the so-called path of totality between Oregon and South Carolina to watch the moon blot out the sun. They experienced an eerie darkness that caused the temperatures to drop, birds to fall silent and cicadas to burst into song. For many people, it was a life-changing experience.

For astronomers, the eclipse presented a rare opportunity to conduct solar science. During the 93 minutes it took for the moon’s shadow to travel from coast to coast, they gathered precious data about the sun’s corona, its magnetic field and the outflow of particles known as the solar wind.

“It was fabulous,” said Williams College astronomer Jay Pasachoff, who has now witnessed 34 total solar eclipses, more than anyone else on the planet.

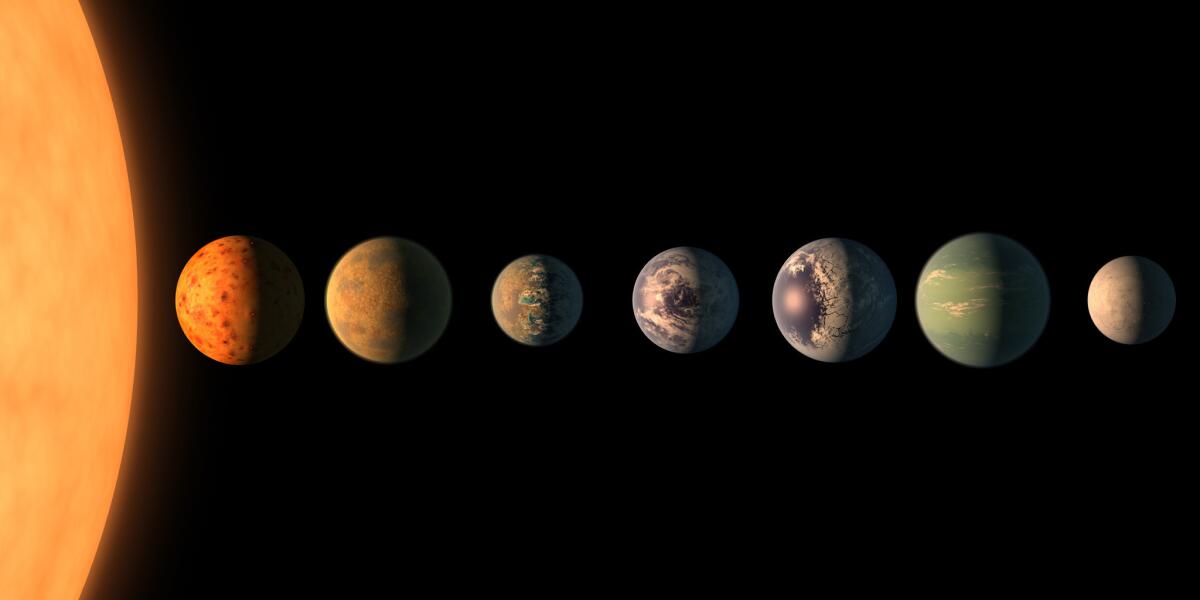

The hunt for another Earth

The discovery of planets around distant stars has become fairly routine. But in February, astronomers announced a particularly tantalizing find: A solar system comprised of not one but seven Earth-sized worlds.

The star at the center of this system is known as TRAPPIST-1. An ultracool dwarf star, it’s much smaller and fainter than our sun. But its planets are close by, and scientists believe three of them are in the habitable zone where water on the surface — should it exist — would be stable in liquid form.

The TRAPPIST-1 system is 39 light-years away, and there is still much that scientists want to learn about it. Among other things, they don’t know whether the planets have atmospheres that would make them truly Earth-like. But astronomers think all seven of them are solid and rocky. The planet known as TRAPPIST-1e receives about the same amount of stellar light as Earth, and TRAPPIST-1f gets an amount similar to Mars. By August, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope had found signs that water may indeed be present on some of the planets.

“With the right atmospheric conditions, there could be water on any of these planets,” Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said in February. “The discovery gives us a hint that finding a second Earth is not just a matter of if but when.”

Gene therapy becomes a reality for American patients

After years of disappointing setbacks, U.S. regulators gave gene therapy treatments their blessing. The Food and Drug Administration approved not one but three of them in 2017.

It began in August with the green light for Kymriah, a treatment for young cancer patients with an aggressive form of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Kymriah is not a typical drug but a personalized medical service that uses genetic engineering to fortify and multiply a patient’s disease-fighting T cells. In clinical trials, 73 of 88 patients who were infused with the engineered cells went into remission.

Yescarta, a similar drug to treat another blood cancer called large B-cell lymphoma, won FDA approval in October. And in December, the agency endorsed Luxturna for patients with vision loss due caused by an inherited form of retinal dystrophy. The drug replaces a faulty gene with a correct version so that patients can make a crucial protein that converts light to an electrical signal in the retina.

“Gene therapy will become a mainstay in treating, and maybe curing, many of our most devastating and intractable illnesses,” Dr. Scott Gottlieb, the FDA’s commissioner, said when he announced Luxturna’s approval. “We’re at a turning point when it comes to this novel form of therapy.”

Marching for science

2017 was a year of political awakening for scientists, spurred by the election of President Trump and the diminished role of research in his administration.

This new degree of engagement was most visible during the March for Science on April 22. Hundreds of thousands of scientists — and their supporters — joined rallies across the country and around the world. They carried signs with slogans like “I can’t believe I’m marching for facts,” and “Society should worry when geeks have to demonstrate!”

Protesters said they feared fact-based research would take a hit in the Trump era. Indeed, the president’s 2018 budget included deep cuts for the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy. It also targeted spending for climate-related research at NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Meanwhile, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, employees were instructed not to use terms like “science-based” and “evidence-based” in budget documents.

Some scientists have gone so far as to run for political office themselves. More than a dozen have been endorsed by 314 Action, an advocacy group that named itself after the value of pi.

Gravitational waves keep making waves

The more you look, the more you find — and that’s especially true when it comes to gravitational waves.

Scientists with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory first detected the waves in 2015. They were ripples in the fabric of space-time caused by the violent smashup of two black holes. They’ve repeated that feat five times since.

The most significant of these occurrences was on Aug. 17. The twin LIGO detectors in the U.S. and the Advanced Virgo Detector in Italy picked up the signature of two colliding neutron stars. Not only did scientists confirm that these powerful events forged heavy elements like gold and platinum, they were able to witness the collision using an array of traditional telescopes that can sense electromagnetic radiation.

That means astronomers will be able to study the same event using visible light, radio waves, X-rays, infrared radiation, ultraviolet light, gamma rays and gravitational waves. Scientists call this multi-messenger astronomy, and they’ve been anticipating its arrival for years. They announced it in October, two weeks after the Nobel Prize in physics was awarded to Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne and Barry Barish for dreaming up and building LIGO in the first place.

Rethinking the history of humans in North America

Excavation for a freeway construction project in San Diego led to a whopping claim: Humans were living in North America roughly 130,000 years ago — about 115,000 years earlier than previously believed.

Evidence for this came in the form of fragmented mastodon fossils, including bones, tusks and teeth. Unlike other fossils found at the site, the mastodon remains were fractured, torn and shattered. Paleontologists with the San Diego Natural History Museum say that the damage occurred shortly after the animals died and that it must have been inflicted by humans, probably to make tools.

Radiometric dating techniques indicate the mastodon died about 130,700 years ago. If humans were indeed in Southern California at the same time, they left nothing of themselves behind.

Some scientists say they find individual elements of this story convincing — even as they insist it’s crazy to think humans reached North America so long ago. Who were these mysterious people? Where did they come from, and how did they get here? Paleontologists are still digging for answers.

Using CRISPR to ‘control human biology’

The folks who predicted big things for the gene-editing system known as CRISPR were on target in 2017.

Scientists used CRISPR to fix a faulty gene that leads to hearing loss in mice and corrected a mutation in human cells that causes sickle cell disease. In a twist, they used CRISPR to activate beneficial genes in order to counteract the effects of faulty ones.

The methods for using CRISPR improved as well. Researchers developed a new type of gene editor that can target and change a single errant letter in a string of DNA without having to cut it. Another group extended it to RNA, allowing scientists to turn the protein-production machinery of certain cells on and off at will.

Don Conrad, a geneticist at Washington University in St. Louis, described the progress like this: “We can control human biology.”

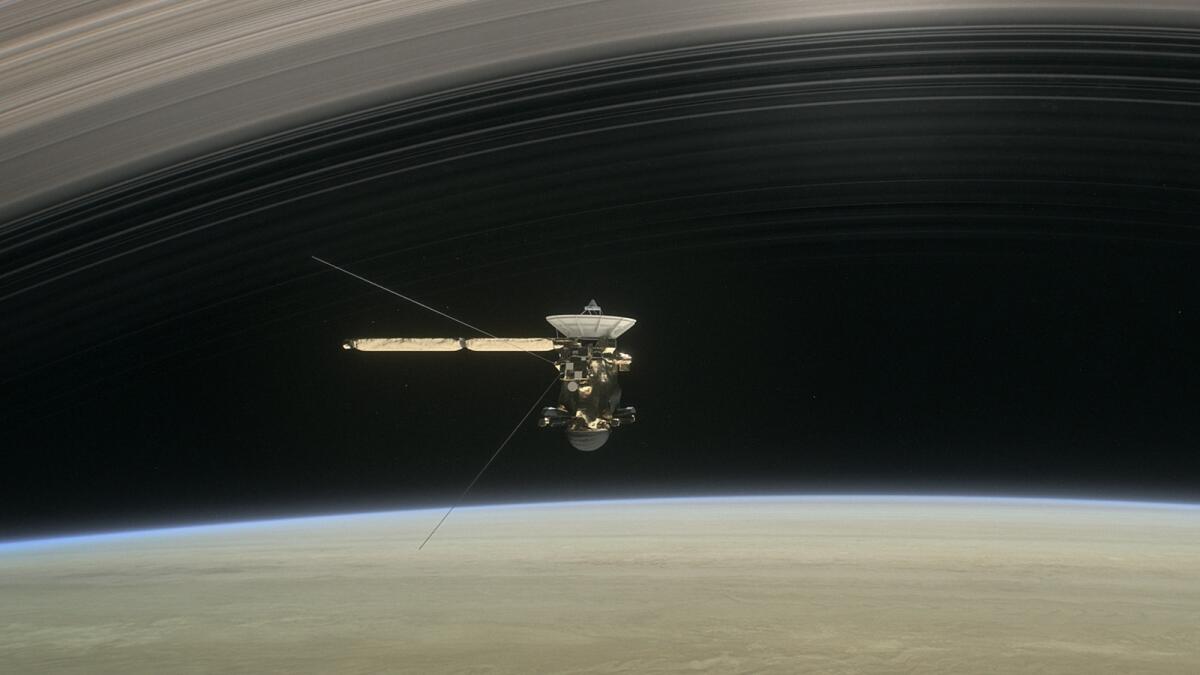

Cassini’s epic mission to Saturn comes to an end

After nearly 20 years in space, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft vaporized in Saturn’s atmosphere. It was a dramatic end to a mission that revolutionized the search for life beyond Earth.

Cassini discovered plumes of water-ice particles emanating from Enceladus, one of dozens of moons in the Saturn system. Mission managers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory steered Cassini through the plumes, allowing scientists to determine that Enceladus has a salty ocean beneath its frozen surface. That ocean may even be warmed by hydrothermal vents similar to those on Earth.

The spacecraft also made multiple trips to Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, and found that it has hydrocarbon lakes and seas. As far as scientists know, Titan and Earth are the only places in the solar system where liquid is stable on the surface.

If there is life elsewhere in the solar system, Enceladus and Titan are two of the most promising locales. NASA is now giving serious consideration to a mission, dubbed Dragonfly, that would make several stops on Titan’s surface.

Before its 13-year stay at Saturn ended on Sept. 15, Cassini witnessed the birth of mini-moonlets in the planet’s rings; spotted massive hurricanes on its poles; and found six new confirmed moons along with a number of faint rings. Some of the scientists and engineers who worked with the spacecraft over the years are still mourning their loss.

Getting to the root of CTE

Scientists deepened their understanding of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the enigmatic brain disorder that afflicts some football players.

In a blockbuster study released in July, researchers from Boston University Medical School’s Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Center examined 202 brains of deceased football players and found evidence of CTE in 88% of them. What’s more, of the 111 brains from athletes who played in the National Football League, all but one had the distinctive tangles, plaques and protein clumps that experts now recognize as hallmarks of CTE.

The large sample of post-mortem brains allowed scientists to discern certain patterns, including a link between years played and disease risk. Men who had mild CTE played football for an average of 13 years, while those with severe disease played for an average of nearly 16 years. That fits with the theory that the more concussions a player suffers, the greater his degree of impairment.

But mysteries remain, including why some of the men who had serious behavioral symptoms had only mild brain abnormalities. Scientists also are investigating whether a player’s age when he starts playing football — and when he first experiences blows to the head — are important factors.

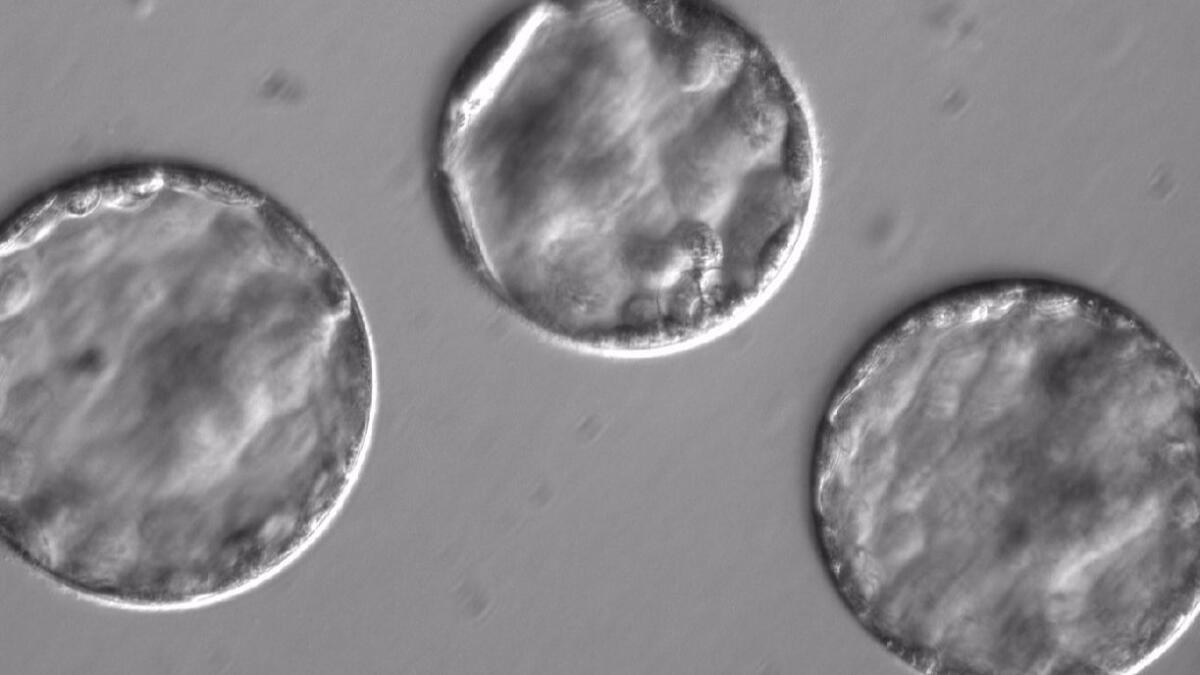

Editing the DNA of human embryos

Scientists edited the DNA of human embryos to eliminate a mutation that causes inherited hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a form of heart disease that can kill its victims in the prime of their lives. The fix, announced in August, erased the mutation not only in the embryos themselves but in the DNA that was destined for their progeny.

The experiments marked the first time scientists had carried out “germ-line editing” in human embryos. By repairing DNA errors in sperm and egg cells, researchers hope to prevent the spread of debilitating or fatal diseases to future generations. Study leader Shoukhrat Mitalipov of Oregon Health & Science University said the technique might someday correct mutations that lead to cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy and certain cancers.

But others worry the advance will give parents the power to create designer babies with desirable traits, such as extraordinary musical talent or exceptional athletic skill. That is currently forbidden; the FDA allows germ-line editing for research purposes only (and the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine recommends that such research be restricted to diseases that can’t readily be treated in other ways). Still, some bioethicists fear that doctors will find ways to offer this controversial service outside the U.S., beyond the FDA’s jurisdiction.

Times staff writers Melissa Healy, Amina Khan and Deborah Netburn contributed to this report.

Follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and "like" Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

Watch robots do chin-ups, push-ups and sit-ups for the sake of science

Gene-editing breakthrough found to minimize hearing loss in mice could help humans

Kale and other leafy vegetables may make your brain seem 11 years younger