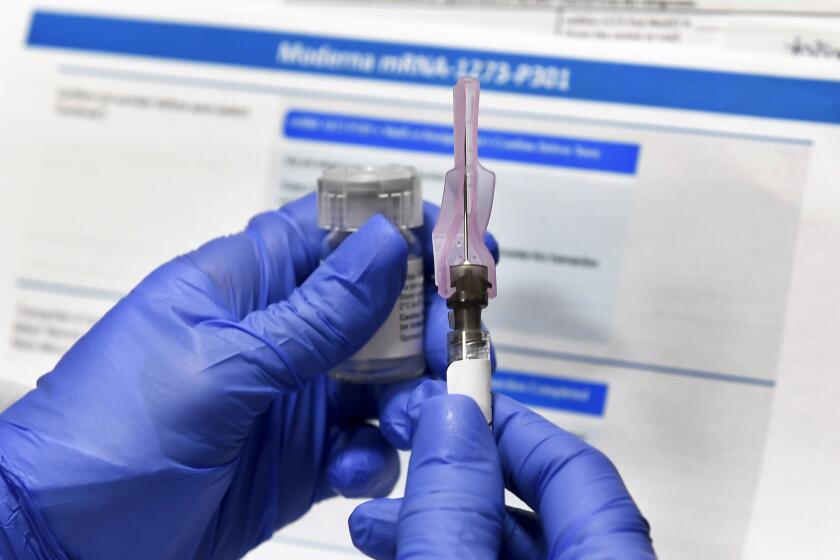

Q&A: How far can Trump go in pushing a COVID-19 vaccine that isn’t ready?

- Share via

We all want a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as we can get it, and we’d like to know that the vaccine is safe and actually works. Those two desires are at cross-purposes now, since the testing required to vet a new vaccine takes time.

President Trump has made clear that his top priority is speed. For a time, his administration rejected the Food and Drug Administration’s proposed criteria for assessing vaccine candidates — criteria which make it all but impossible to have a vaccine available by election day.

This week, the White House relented and approved the FDA’s proposal. But the question remains: Could Trump force regulators or companies to give the public a COVID-19 vaccine that didn’t meet scientific standards?

The short answer: It depends.

To play out the possibilities, you’ll need to understand some facts about vaccine science, the political calculations and commercial motives of the central characters, and what it will take to get Americans to trust a vaccine so we have a shot at returning to something resembling normal life.

Let’s get started.

Why do we think Trump values speed more than safety?

There’s no question the president would like to see a vaccine approved before ballots are cast. He appears eager to show voters that he responded to the pandemic by getting a vaccine developed and deployed in record time.

“Moving faster than anticipated. Good news ahead!” he tweeted in June. “Now the Vaccines (Plus) are coming, and fast!” he tweeted in early September. “The Democrats are just ANGRY that the vaccine and delivery are so far ahead of schedule. They hate what they are seeing,” he complained later that month.

His preoccupation with the timing has caused him to clash with officials who said vaccine approvals might not come until 2021. Chief among them has been Coronavirus Task Force member Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious diseases specialist. But lately, it’s been FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn’s time in the barrel.

“New FDA Rules make it more difficult for them to speed up vaccines for approval before Election Day. Just another political hit job!” he tweeted at Hahn.

Although Trump will almost certainly miss his self-imposed election-day deadline, his administration is still on track to achieve a speed record. Vaccines typically take about a decade to develop, test and deploy. Even if it takes several more months for the first COVID-19 vaccine to clear the FDA’s hurdles, it will have emerged in roughly a year from the time the virus was identified.

Has the FDA done something that could delay a vaccine?

Not with that intent.

The FDA’s guidelines to vaccine makers require them to keep track of each person in their clinical trial for two months after receiving a dose of vaccine. That’s how long it should take for roughly half of the vaccine-related “adverse events” to crop up, according to Dr. Peter Marks, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. That lengthy follow-up is needed to boost the agency’s confidence in the vaccine safety data it reviews.

With that requirement in place, there is no way for any vaccine clinical trial in the U.S. to wrap up in time for a pre-election day announcement. Perhaps that’s why Trump shifted his focus this week and began touting the experimental antibody treatment from Regeneron that he received at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

What about the companies that made the vaccines? Don’t they want approval as quickly as possible?

The companies that field a vaccine that safely protects against coronavirus infection — even if it prevents infection in just 50% of cases — will become rich and respected. (There probably will be more than one vaccine candidate authorized by the FDA.)

But the company whose vaccine sickens a significant number of Americans will wish it had never heard of Operation Warp Speed, the government program to accelerate vaccine development.

That company probably wouldn’t face financial consequences for sickening its customers: Since the 1980s, the feds have shielded the makers of virtually all vaccines from liability to keep them from exiting a business that comes with modest profits and lots of lawsuits alleging injury. But a COVID-19 vaccine that causes serious side effects in a broad swath of people would be a serious PR disaster.

Speeding up the testing process by a couple of months would not pay off for them in the long run.

Top executives of nine drugmakers likely to produce the first coronavirus vaccines signed a pledge to boost public confidence in approved vaccines.

Last month, nine companies leading the race to produce COVID-19 vaccines pledged not to seek FDA authorization or approval until the safety and efficacy of their products had been established in legitimate clinical trials. Their joint declaration was intended to demonstrate their “commitment to uphold the integrity of the scientific process,” they said.

The statement was widely seen as a rebuke to President Trump.

Can Trump change the FDA’s criteria for evaluating vaccine candidates? Can he force the FDA to approve one?

Yes. Trump has the legal authority to make the FDA approve an experimental vaccine on his say-so because he is the chief executive and this is an executive agency.

In the midst of a national emergency, the FDA has a great deal of legal latitude in granting emergency use authorization to drugs or vaccines. It can also modify its criteria as circumstances change.

The Trump administration has overruled scientists on a wide range of issues overseen by several federal regulatory agencies. Under its regulation-reduction initiatives, it has loosened air pollution and clean water strictures, eased automobile emission standards, and relaxed safety protections for workers. Most of these rollbacks have been made by discounting scientific studies used to undergird existing regulations or by changing the way a regulation’s effect is measured.

When the Environmental Protection Agency unveiled a proposal this week to give states more latitude in regulating pollution from power plants within their borders, it came with a sobering forecast of its likely impact on Americans’ health.

The president has chafed against the FDA’s time-consuming drug-approval record for years. With far less fanfare, he has sought to speed drug approvals, change the way clinical trials are conducted, and make the FDA give dying patients early access to drugs it has not deemed safe or effective.

Such efficiencies have allowed a cautious, science-driven agency to respond more quickly to the urgent needs of a pandemic. But if a Trump official were determined to bend the FDA’s schedule for political reasons, the administration’s track record of shifting scientific goalposts would make it easier to do so.

Are there non-scientific reasons for the FDA to impose time-consuming requirements on vaccine trials?

Yes. But they’re not the reasons Trump has alleged, or that his conspiratorial insinuations might have you believe.

The FDA urgently needs to shore up Americans’ confidence in the safety of the coronavirus vaccine — it’s the only way to ensure that a high proportion of Americans are willing to take a vaccine it approves.

That’s a tall order. As recently as May, 72% of Americans said they “probably” or “definitely” would get vaccinated once COVID-19 immunizations were available, and just 27% said they probably or definitely would not, according to a Pew Research survey. By September, 49% of Americans told Pew they “probably” or “definitely” would not get the vaccine, and only 51% said they “probably” or “definitely” would.

The goal of a vaccine is to establish “herd immunity.” That’s when so many people have been made immune to the coronavirus that it can’t easily find new people to infect. Even those who can’t (or won’t) get the vaccine will be protected because the virus won’t have an easy path to reach them. At that point, new transmissions will slow and outbreaks will be fewer and more short-lived. And the pandemic will be over.

Israeli scientists say they can mimic the effects of a vaccination campaign if certain people willingly get infected with the coronavirus and recover.

Experts have estimated that to achieve such population-wide protection in the United States, 70% to 80% of the U.S. population will need to gain immunity as a result of a COVID-19 vaccine or because they’ve survived the disease themselves.

Those herd immunity estimates are really rough, and they will vary from place to place and among populations. For instance, vaccination rates might need to be higher among frontline workers and people of color.

But people of color, already disproportionately affected by the pandemic, have endured a long history of abuses at the hands of medical researchers. Their resulting mistrust of the medical establishment will heighten the challenge of persuading them to take the COVID-19 vaccine.

And the vaccination rates needed to achieve herd immunity might well exceed 70% or 80%, since the first crop of vaccines won’t be 100% effective. In June, the FDA said it would consider approving vaccine candidates that prevent disease or decrease its severity in as little as 50% of those who get it.

With the proportion of Americans willing to get vaccinated well below the threshold needed for herd immunity, the FDA has some reassuring to do.

There’s science in that, but lots of optics too.