Why RFK Jr. nomination sets off alarms among many public health specialists

- Share via

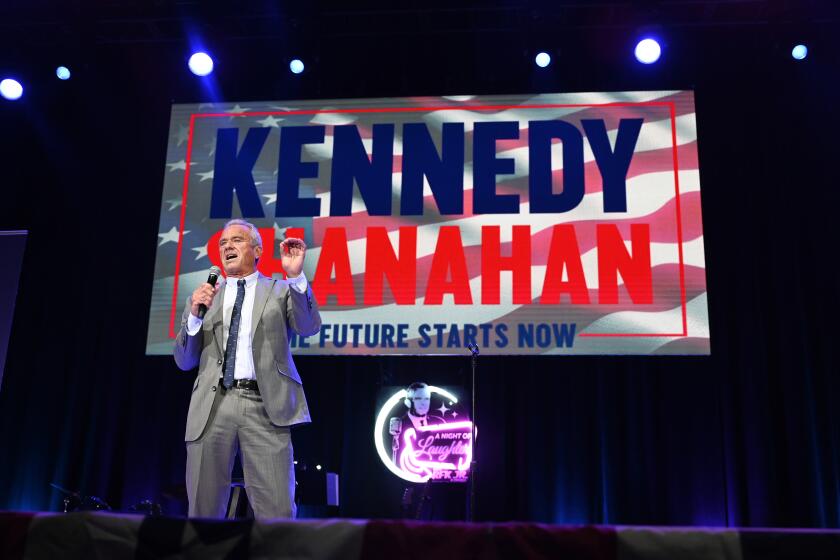

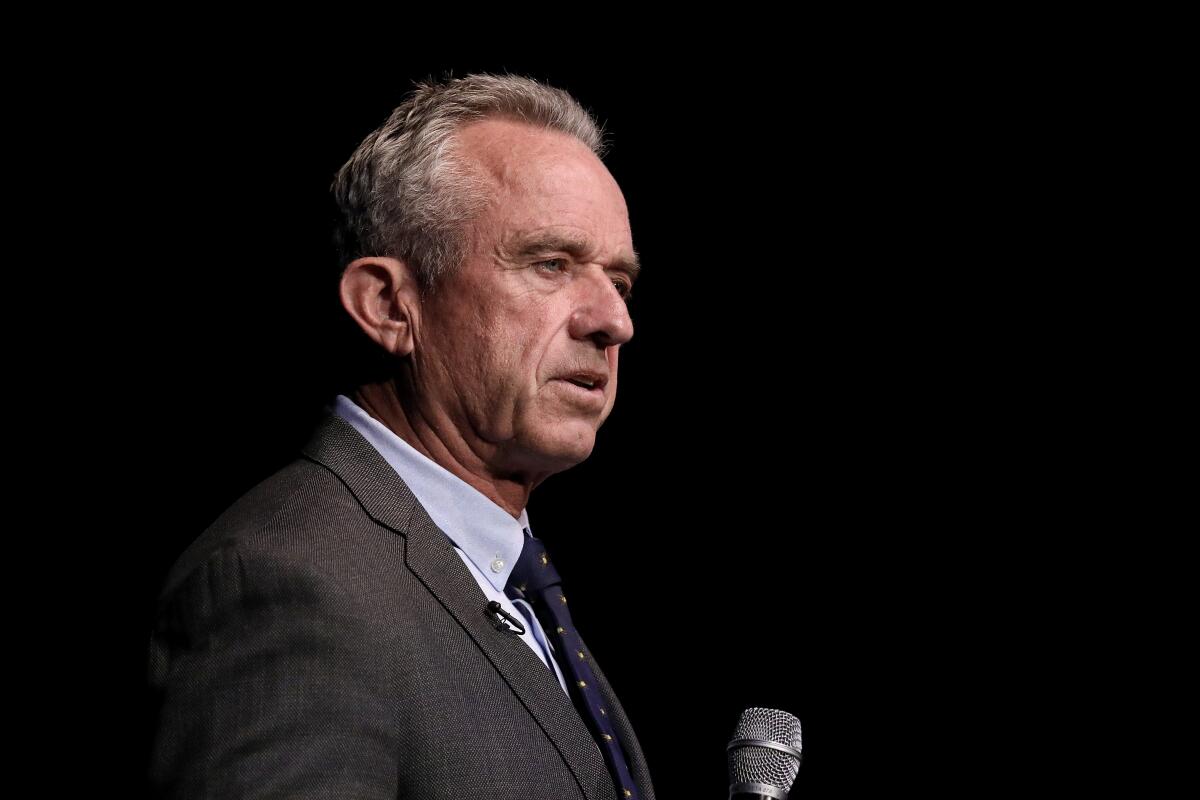

With President-elect Donald Trump’s nomination of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to be Health and Human Services secretary, public health leaders are voicing fears that federal health agencies will be weakened even as the country faces rising threats from infectious diseases, emboldened industry lobbyists and the spread of medical misinformation.

If confirmed to lead Health and Human Services, Kennedy — a proponent of fringe medical conspiracy theories and self-described “poster child for the anti-vax movement” — would have oversight of institutions including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and National Institutes of Health.

Like the two most recently confirmed Health secretaries, Xavier Becerra and Alex Azar, Kennedy is a lawyer with no formal scientific or medical credentials. His purview would include programs and agencies he has fiercely criticized, often in ways that opponents say distort or ignore facts and misinterpret science.

Many of the problems Kennedy has said he wants to tackle are concerns shared broadly by healthcare providers, public health officials and members of the public. They include pervasive chronic disease, poor nutrition and the ubiquity of processed foods containing artificial chemicals.

From family planning to hospital bills, the new Trump administration has the potential to affect a wide range of policies in the Golden State and beyond.

But his nomination has alarmed many public health and medical officials, who say they are worried that the solutions Kennedy might deem appropriate could undermine Americans’ health in the long run.

“Putting somebody in charge who is unable to discern the difference between good and bad science is really dangerous for the American people,” said Dr. Peter Lurie, president and executive director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest.

“Yes, there are some things that he supports that we would agree with, but they feel more like the stopped clock that’s right twice a day,” Lurie said, citing food additives as one example. “There are opportunities for small victories. … But overall, it’s dissolved in so many bad ideas that it’s absolutely not worth it.”

Kennedy declined to discuss his plans for the department with The Times, but has indicated some priorities for the agency in previous public statements.

For instance, he said Trump would advise against water fluoridation on his first day in office. He told NBC News he wouldn’t “take away” vaccines, but he would “make sure scientific safety studies and efficacy are out there, and people can make individual assessments about whether that product is going to be good for them.”

More than half a dozen experts who spoke with The Times warned that Kennedy’s suggestions that the science around vaccines is unsound would undercut public health.

The United States has “the best vaccine safety system in the world,” said said Dr. Richard Besser, a former acting CDC director who now leads the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. “RFK Jr. has done a lot to undermine confidence in that.”

Indeed, cases of measles have been rising in the U.S. as childhood vaccinations have lagged amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The CDC has identified 277 measles cases this year, up from 59 in 2023.

“I don’t want to have to see us go backwards in order to remind ourselves that vaccines work,” Dr. Mandy Cohen, the CDC’s director, said last week at the Milken Institute Future of Health Summit in Washington, D.C.

Kennedy’s zeal to remove fluoride from drinking water on the claim that the mineral causes neurodevelopmental disorders and other health issues is another example of shirking the best science, said Dr. Walter Willett, a professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. described fluoride, which occurs naturally in all fresh water supplies, as an ‘industrial waste’ associated with various health risks.

“That has been looked at carefully, and there has not been evidence of a link,” Willett said. “On the other hand, there are serious problems with lead in water systems.”

Vaccines and fluoride are just two areas where Kennedy will have an opportunity to implement ideas that lack strong scientific support.

Last month, he decried what he called the FDA’s “aggressive suppression” of unproven health remedies such as dietary supplements and ivermectin, warning on X: “If you work for the FDA and are part of this corrupt system, I have two messages for you: 1. Preserve your records, and 2. Pack your bags.”

But food safety advocates who have shared many of Kennedy’s criticisms about lax regulation said gutting the agency is not the answer. Any effort to reduce or eliminate chemical additives in foods would require experienced staffers to draft new rules and shepherd them through the required regulatory process, said Ken Cook, president of the nonprofit Environmental Working Group.

“If you’ve gotten rid of all the bureaucrats, who’s going to write the regulation?” Cook asked.

Or consider the FDA’s reliance on user fees from companies seeking approval of their medical products. The fees make up nearly half of the agency’s operating budget. Kennedy and others have criticized such fees, but if those dollars went away, Congress would be unlikely to backfill them, Lurie said.

“Ending user fees is tantamount to starving the agency,” he said. “That would mean a food program that’s limited in what it can do, drugs coming to market more slowly, and vaccines that are even less well-monitored for safety.”

Lurie said he wouldn’t be surprised to see Kennedy task researchers at the National Institutes of Health with looking for damaging side effects of vaccines and elusive benefits of potential therapies that have already been shown ineffective, such as chelation as a treatment for autism and ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19.

“He seems to think these hold great promise,” Lurie said. “Most of those ideas are sinkholes for government spending, which is ironic given the Trump administration’s purported devotion to efficiency.”

As significant as the Health secretary’s role is, Kennedy would still find his powers curtailed by the agency’s limited reach — and potentially by the whims of his boss.

Willett said he agrees with Kennedy that the nation’s health is in decline, and that our food and healthcare systems are “in many ways dysfunctional.” The Harvard professor would welcome efforts to crack down on the amount of salt allowed in foods and to curtail consumption of added sugars, refined grains and sugar-sweetened beverages.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., in a 2012 deposition, reportedly cited health issues that he attributed to a worm in his brain.

But if Kennedy takes steps like these, “we know for sure he will run into resistance from industry,” Willett said. “It would be interesting to see if he’s prepared to take on Coca-Cola.”

For the record:

1:02 a.m. Nov. 17, 2024An earlier version of this article said the Agriculture Department was responsible for regulating pesticide use on crops. That job belongs to the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Agriculture Department plays an advisory role.

Although Kennedy is passionate about reducing pesticides and other chemicals in foods, it’s up to the Environmental Protection Agency, with input from the Agriculture Department, to regulate pesticide use on crops and determine what exposure levels are considered safe for people, said Cook, the Environmental Working Group’s president. Nor would Kennedy have the power to reform farm subsidies to encourage organic and regenerative agriculture.

“He doesn’t have much purchase on pesticides from his perch,” Cook said. “That’s not really an HHS thing or an FDA thing.”

The FDA does have the authority to regulate chemicals from food packaging that can find their way into food, and Kennedy could prioritize that, Cook said.

It’s also possible that Kennedy could protect the budgets of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Cook said.

To help achieve his goals, Kennedy has invited the public to weigh in on people who could fill important roles within federal health agencies.

Names that have garnered thousands of votes in the “America’s Health” category of his “Nominees for the People” website include Dr. Sherri Tenpenny, who claimed COVID-19 vaccines made people magnetic, and Dr. Simone Gold, the anti-vaccine Beverly Hills physician whose medical license was suspended after she pleaded guilty to unlawfully entering the U.S. Capitol during the Jan. 6, 2021, attack. (Her license has since been restored.)

Kennedy’s accession to the top Health and Human Services post is not yet certain. Cabinet positions are supposed to be confirmed by the Senate, though Trump has suggested that he may use recess appointments to bypass the need for lawmakers’ approval.

Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Assn., said that even if Kennedy wins confirmation, it’s uncertain how long he would remain in Trump’s good graces.

“I remind folks that his first Health secretary didn’t last a year,” Benjamin said. “We’ll see what happens here.”