The wild story of how Anaheim’s leaders bungled the Angels Stadium deal and betrayed their city

In 2005, about halfway through our two pleasant decades of life without the NFL, the city of Anaheim staged a news conference to unveil its plan to lure the league to town. The NFL loved a splashy pitch, even if the league had no interest in what you were pitching.

The news conference was almost over when a first-term city councilman interrupted the choreographed presentation. The councilman argued that the plan was so tilted in favor of the NFL that it could not possibly be in the best interests of the taxpayers of Anaheim. He had to speak up, he said, because he had been “shut out” by city leaders from negotiations with the NFL, and from the news conference itself.

“People should know the truth,” he said.

He later explained: “All of us on council all have equal votes. We should all have equal time to talk.”

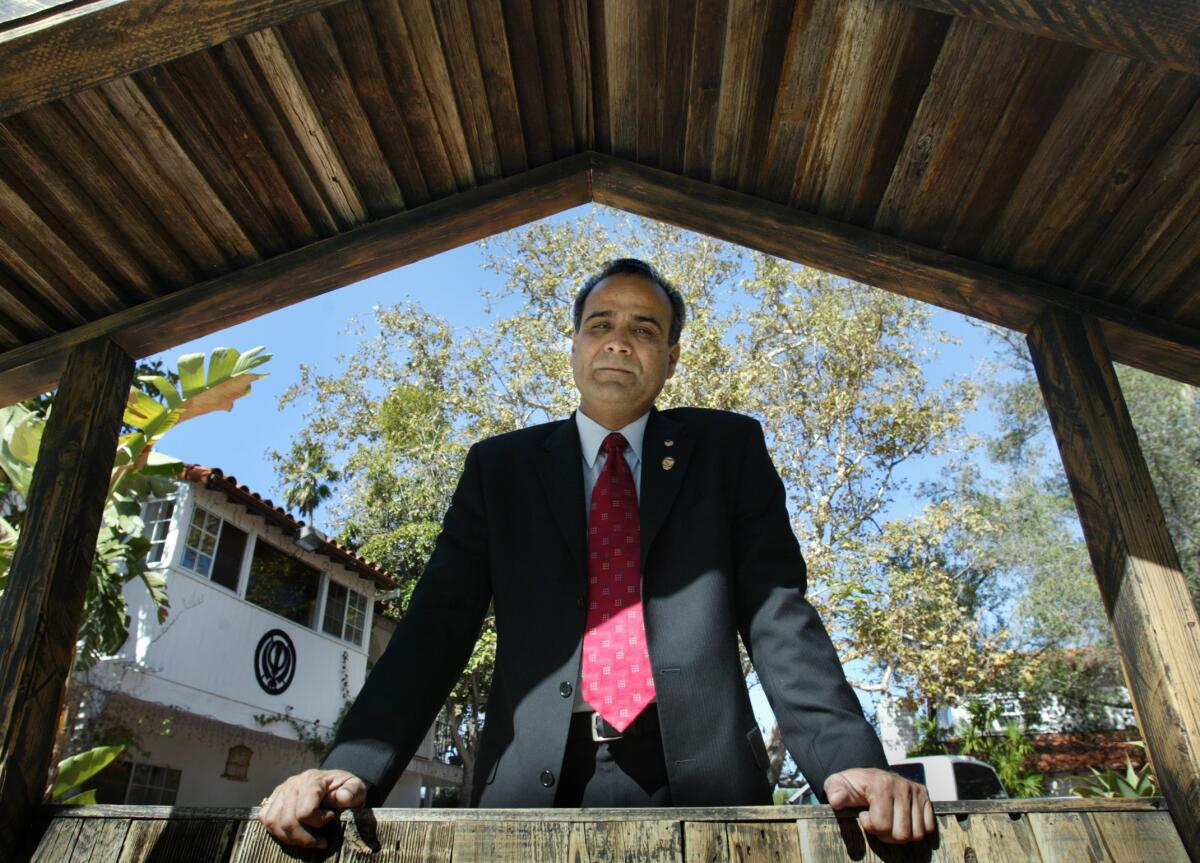

That councilman was Harry Sidhu.

In 2018, Sidhu was elected mayor. From then until last week, when an FBI affidavit revealed Sidhu was under investigation for public corruption and other offenses, Sidhu ran negotiations with the Angels exactly how he had bemoaned city leaders had run negotiations with the NFL in 2005: obscuring the truth from the public and the full council, and trying to silence the critics.

The wide-ranging investigation includes the sale of Angel Stadium and allegations of bribery involving Anaheim’s mayor.

On Monday, Sidhu resigned as mayor. On Tuesday, the city council will try to figure out what the hell to do about the deal to sell Angel Stadium and the land around it to Angels owner Arte Moreno.

Moreno, through an attorney, has demanded the council approve the deal. The state housing agency has warned the council not to approve the deal. Litigation could follow either way, or Moreno could walk away and leave the city to rue its undeveloped acres of parking lots for decades to come.

Sidhu wanted the Angels deal to be his legacy. Instead, his legacy is this mess, the result of running the city on behalf of a “cabal” of special interests rather than on behalf of the taxpayers, according to FBI affidavits made public last week.

The 2005 version of Sidhu would have been proud of Tom Tait. In 2013, Tait was the mayor, and the city was considering a different stadium deal with the Angels. The city had been presented with a predictably rosy economic impact report, and Tait thought the numbers defied common sense.

In Anaheim, fans drive into the parking lot, watch the game and drive home. There is no significant mass transit. If fans grab a drink or dinner before the game, they might walk a couple blocks — perhaps into Orange, outside the Anaheim city limits. Yet the representative of the firm that prepared the report testified about the windfall that awaited Anaheim, based on surveys done in Chicago, Houston, Minneapolis and San Diego.

“Based on a survey here in Anaheim?” Tait asked.

“We haven’t done it here,” the representative confessed.

With Sidhu as mayor, the city did not bother to commission an economic impact report. It accepted the one submitted by Moreno’s company.

With Sidhu as mayor, the city voluntarily surrendered its negotiating leverage to the Angels. In January 2019, after the Angels had opted out of their stadium lease, they had nine months left on the lease.

“Tonight,” Sidhu announced at a Jan. 15, 2019 council meeting, “I am asking my council colleagues to consider a one-year extension to the current Angels lease, through the end of 2020.”

A city news release before the meeting said the council would “consider a one-year stadium lease extension.” A city fact sheet after the meeting said the council had approved “extending lease end from Oct. 15, 2019 to Dec. 31, 2020, to allow time to consider a new long-term lease.”

Sidhu and the council majority refused to ask the Angels for anything in return, not even a promise not to talk to any other city while working toward that new long-term lease.

The council debated the extension for one hour and 23 minutes, never once with the full truth up for discussion: The extension was for the opt-out clause, not the lease. The lease itself had been reinstated.

The Angels suddenly had 10 years left on their lease.

On July 16, 2019, after rebuffing efforts to include multiple members of the council on the city’s negotiating team, Sidhu persuaded his colleagues to appoint him as the sole elected official on the team.

If a new deal did not happen, the city could not kick out the Angels after 2020. Instead, the Angels had their Plan B: They would remain at Angel Stadium through 2029, with options through 2038 — and with control over development on the property.

The city later released an appraisal that showed the site could be worth $500 million with the Angels gone and the stadium demolished — but months after Sidhu had persuaded his council colleagues to take that option off the table, without anyone saying so.

“I did not speak to, nor did staff speak to, ramifications related to the value of the property,” city manager Chris Zapata said to the council in August 2019, after councilmembers Denise Barnes and Jose Moreno had discovered exactly what they had voted for in January.

The ostensible reason for the extension, as the city executive in charge of the stadium said at that January meeting, was to allow “time to work out a likely complicated transaction.”

Facing pressure to delay or cancel the Angel Stadium sale amid a corruption probe, the Angels gave the City Council 25 days to grant final approval.

It was indeed complicated: a $325-million sale of the stadium site to Arte Moreno’s fledgling development company, which would have 30 years to build a village of homes, shops, restaurants, hotels and offices atop 130 acres of parking lots, with provisions in the deal to lower the cash price as an inducement for the company to include affordable housing and a signature park within the project.

After the deal was announced, The Los Angeles Times reported the actual cash price would be steeply reduced, “possibly by half.” Nine months after the deal was approved, the city revealed the actual cash price: $150 million.

The deal was announced on Dec. 4, 2019. Yet, according to a timeline posted on the city website, the city and the Angels did not hold a negotiating session until Nov. 15, 2019.

At that January meeting, Zapata was portrayed as the city’s lead negotiator. Zapata had experience negotiating with sports teams at previous jobs in city governments in Arizona and California.

On July 16, 2019, after rebuffing efforts to include multiple members of the council on the city’s negotiating team, Sidhu persuaded his colleagues to appoint him as the sole elected official on the team.

According to one of the FBI affidavits, Sidhu received the city’s confidential land appraisal in September and “provided the appraisal figures … to be shared with representatives from the Angels,” two months before the city said it had started negotiations with the Angels. FBI agent Brian Adkins wrote that Sidhu’s disclosure of confidential information “may have violated the Brown Act,” the state’s government transparency law.

On Monday, Paul Meyer, the attorney for Sidhu, said in a statement that “no closed session material, no secret information, was disclosed by Mayor Sidhu.” Meyer also said “a fair and thorough investigation” would show “Sidhu did not leak secret information in the hopes of a later campaign contribution.”

In 2020, Zapata was fired by Sidhu and the council majority, after reportedly clashing over publicly funding a city tourist bureau during the pandemic. In January of this year, Zapata and Jose Moreno testified that the city privately had agreed to sell rather than lease the property to the Angels, also two months before the city said it had started negotiations with the Angels.

In March, an Orange County Superior Court judge ruled that he did not believe what Zapata and Jose Moreno had said, and so he would not overturn the sale on the basis the city had violated the Brown Act. However, in an affidavit, Adkins wrote that Sidhu’s actions and subsequent attempt to “conceal those actions from an Orange County grand jury … may have affected the ruling.”

One month earlier, two representatives of the Anaheim Chamber of Commerce had appeared before the city council, urging the council to keep the Angels in Anaheim. The plea was made two years after the window for the Angels to opt out of their reinstated lease had expired.

That is the only note the chamber knows how to play.

The chamber — a leader of the so-called “cabal” that allegedly runs the city — had spent the better part of a decade dressing people in red “Keep the Angels” shirts at council meetings and repeating that Arte Moreno had numerous cities in Southern California that would pay to build his team a stadium, without providing any evidence to support that claim. In fact, when Moreno looked at Tustin, city officials said they would be happy to welcome him so long as he paid for the land and the cost of building the stadium.

Alas, at least the way the FBI tells it, getting the deal done was not enough for Sidhu.

The chamber’s former chief executive, Todd Ament, was charged last week with lying to a mortgage lender about his assets. Ament is a cooperating witness in the investigation into Sidhu, according to one of the affidavits.

In 2019, on a Friday five days before Christmas, the council gathered to approve the Angels deal. Barnes wondered why the council should approve the deal when city executives admitted they had no idea who made up Arte Moreno’s development company besides Moreno, and whether anyone involved with the company had actual development experience.

Jose Moreno had been rebuffed when he asked for a 30-day review period for the deal. Sidhu had long tired of Jose Moreno, who repeatedly asked detailed questions and made long and dissenting statements on items the council majority was ready to approve. Sidhu previously had pushed through a rules change: Three votes rather than two would be needed to put an item on the council agenda. Jose Moreno had only one ally on the council.

In that 2005 news conference, when he was in the council minority, Sidhu gave his cellphone number to any reporter who would take it. As mayor, Sidhu preferred to let carefully crafted statements and op-ed pieces do the talking for him.

Jose Moreno was more than happy to talk to reporters, raising issues about the deal in a format where the council majority could not silence him, and some city leaders tired of reading his comments. He believed he had been “shut out,” just as Sidhu believed he had been “shut out” in 2005. When the city finally had an Angels deal to announce, a city official said Sidhu made sure two media outlets that had extensively quoted Jose Moreno in their coverage were not invited to the news conference. (The Times was one of them.)

Harry Sidhu said in a statement released by his lawyer that he did nothing wrong.

There were two reasons the city council needed to approve the deal on that Friday before Christmas. The first reason, and the most prominent: the city had promised a deal by year’s end, because the Angels had until then to trigger the opt-out clause in the reinstated lease.

The second reason, whispered in the hallway outside the council chamber: A state law called the Surplus Land Act, which was changing on Jan. 1, 2020. If the city could beat that deadline, city officials believed, the act would not apply to the Angels deal.

The state would later disagree with that assertion, loudly and repeatedly, then charge the city with violating the law, which was intended to spur construction of affordable housing on public land. The city could have been liable for a $96-million fine. In order to settle the matter, the city agreed to divert $96 million used for development credits at the stadium toward the construction of affordable housing elsewhere in Anaheim.

An Orange County Superior Court judge put that settlement on hold last week, after the disclosure of the investigation into Sidhu.

None of this had to happen. Sidhu had the council majority. He had the votes. He could have indulged residents and the council minority. He could have been up front about choosing to keep baseball rather than maximize land value.

Alas, at least the way the FBI tells it, getting the deal done was not enough for Sidhu. Getting the deal done in time for him to hit up the Angels was the priority, in the hope they would kick in at least $1 million to his reelection campaign.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

The city can try to shake some more money loose on the sale, but there is no guarantee the city can maximize dollars without risking the other benefits of the deal, and no promise Arte Moreno would pay more without getting something in return. Indeed, to induce Moreno to help settle the affordable housing issue with the state, the city released him from his obligation to include hundreds of affordable units within the Angel Stadium development.

No one on the council — not even Jose Moreno — objects to securing the Angels as the long-term anchor on the property. No one on the council has advocated for turning the stadium site into the third Disney theme park in Anaheim, or for plopping nothing but homes into what the city has planned as a sports-themed entertainment district.

Under the current version of the deal, the Angels would stay for decades, run the stadium at their expense, and make a neighborhood come to life atop the parking lots, generating tax revenue on land the city has failed to develop for more than half a century. A city that desperately needs housing would get thousands more homes, affordable and otherwise.

All of that is in jeopardy now, because Mayor Harry Sidhu did not abide by the five wise words of councilman Harry Sidhu: “People should know the truth.”

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.