Baseball scout tells of when the play was the thing, not the money

George Genovese, 91, still a consultant to the Dodgers, made $80 a month in 1940 in his first job with a pro baseball team. The thrill of the ballpark has not diminished. ‘It’s in my blood,’ he says.

- Share via

The old baseball scout pulls his cap down over his face, peering through one of the eyelets sewn into the crown. It is a trick he learned in the 1940s.

"Like I've got a camera," he says. "I can zero in on one player."

Sitting in his usual spot overlooking the third-base line at Dodger Stadium, George Genovese focuses on the talented rookie, Yasiel Puig, in center field.

With everything else blocked from view, Genovese watches and waits, listening for the crack of the bat.

"The best fielders know how to anticipate where the ball is going," he says. "They take a step before it's hit."

A hint of New York marks his accent, a remnant from his youth. And there's an occasional boyish smile that belies the shock of white hair on his head. All his years in baseball — a lifetime of playing, managing and prowling for fresh talent — have not dampened the thrill of the ballpark.

"It's in my blood," he says. "You know?"

These days, Genovese considers himself retired. But the 91-year-old still serves as a consultant to the Dodgers, and the team leaves him a ticket at the gate for home games.

On a summer evening in Chavez Ravine, he analyzes the players on the field, the strengths and weaknesses of each team. When the conversation shifts to the old days, he talks about something more important — the heart of the game.

Though the Great Depression had taken hold, Genovese had the best sort of childhood. It was baseball's golden age.

Even semi-pro clubs had talent because good players could not afford to leave their jobs for the modest salaries offered by major-league franchises.

The West Brighton Cardinals held night games at a park near Genovese's home on Staten Island, stringing up lights with cords that crisscrossed the field. The boy watched his oldest brothers, Dom and Chick, play there.

"Then they heard the House of David paid more," he recalls. "So they quit and joined that team."

The House of David holds a special place in baseball folklore. Formed by a Michigan religious sect in the early 1900s, it barnstormed the country with players wearing beards and long hair. Eventually, the sect recruited talented outsiders to fortify the roster.

Whenever they came through New York, Dom and Chick let their kid brother serve as batboy and enlisted their mother to cook.

"I remember a bunch of them coming to our home for Sunday dinner," Genovese says. "I got such a kick out of watching these guys eat spaghetti with their big beards."

The House of David scheduled doubleheaders against local opponents on Sundays. Afterward, everyone squeezed into big Pierce Arrows and rode across the bridge for a night game in New Jersey, letting their sweaty uniforms out the windows to flap dry.

Genovese reminisces about those days while watching modern athletes who earn millions.

"Money wasn't the object back then," he says. "The object was to play."

By 1940, Genovese had turned himself into a shortstop who, at 5 feet 6, could hit and run.

I thought I was high-priced. Some of the guys I played with were getting $65 or $70."— George Genovese

His church league director found him a ride to Connecticut for a St. Louis Cardinals tryout, in which he beat out hundreds of prospects to earn his first pro contract. The Cardinals paid him $80 a month.

"I thought I was high-priced," he says. "Some of the guys I played with were getting $65 or $70."

The organization assigned him to a low-minor league club in Hamilton, Ontario. Arriving by train at 5 a.m., Genovese checked into a hotel and excitedly called his manager.

"Son, get some sleep," said the tired voice at the other end of the line. "Then meet me in the coffee shop at 10 o'clock."

So many years later, Genovese recalls taking a bus to the ballpark and trying on his uniform that day. The team's captain, Hank Redmond, came over to welcome him.

Redmond was an ox of a man who kept chewing tobacco wadded in his cheek. He spit on the rookie's pants.

"What's that for?" Genovese asked.

He recalls Redmond muttering, "Good for the linen," and walking away.

A few hours later, as they lined up before the game, Redmond leaned over and spit again, this time hitting Genovese's shoe. "Good for the leather," the big man said.

Despite cramped locker rooms and long bus rides, nothing could compare to that season. Genovese hit .266 in a league that featured future All-Star pitchers Sal Maglie and Warren Spahn.

Moving into a boarding house with two teammates, the 18-year-old paid $2 a week for rent, $1 extra for laundry. On the way out each day, he left tickets on the table for the landlord.

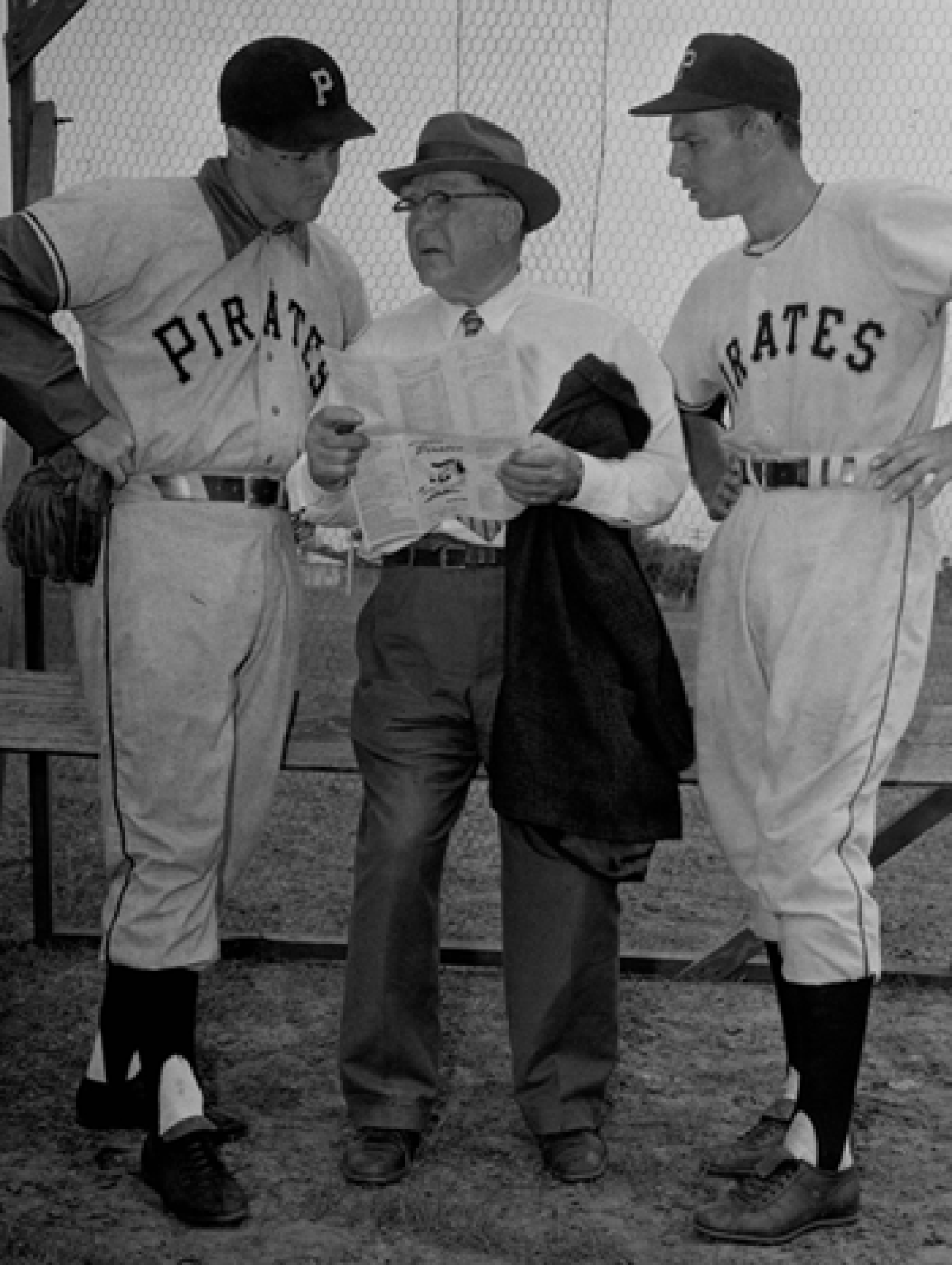

Branch Rickey, 75-year-old chairman of the board of directors of the Pittsburgh Pirates, talks to two Pirates' players in 1957. Rickey is the father of the game's farm system. (Associated Press)

"At night when we got back," he says, "there would be a snack in the refrigerator for us."

The next dozen years took him from Lynchburg to Omaha to Denver, through every level of pro baseball. Genovese won a championship with the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League in the high minors and played briefly for the Washington Senators in the big leagues.

He never wanted it to end, but the famed general manager Branch Rickey finally pulled him aside to tell him that he had lost a step.

It was 1952 and Rickey, running the Pittsburgh Pirates at the time, needed a manager for his minor league team in Batavia, N.Y. Genovese began a new career, working for the man who, among other things, created the framework for the farm system and broke the sport's color barrier by signing Jackie Robinson to the Brooklyn Dodgers.

"Mr. Rickey was an innovator," Genovese says. "I tried to learn everything I could from him."

At spring training that year, Rickey called his managers to a daily meeting. Genovese kept suggesting they release a struggling outfielder, but the boss refused to listen.

"Mr. Rickey put his fingers to his lips," Genovese recalls. "He told me, 'We can't cut that guy. He's my goose-shooter.' "

The rookie manager spent days pondering, troubled as to why he'd never heard that particular baseball term. Then he learned the truth: Rickey loved to hunt and the prospect in question had a duck blind on his family's land.

"Goose-shooter," Genovese says, laughing. "That's why Mr. Rickey kept him around."

Later that year, the organization wanted to release a big left-handed pitcher on the Batavia roster to make room for another prospect. Genovese kept stalling, so Rickey called.

The team traveled in a decrepit bus that broke down frequently. One night, stranded in upstate New York, the players slept in empty cells at a jailhouse.

The big pitcher couldn't help on that occasion, but was a good enough mechanic to get them back on the road other times. Genovese told Rickey: "I can't cut the guy. He's my goose-shooter."

Managers always get fired. If you become a scout, you'll have a job as long as you can see to drive."— A friend said to George Genovese

The minor-league El Paso Sun Kings finished 1963 with a losing record in the Texas League. Their manager, Genovese, received some unsolicited advice.

"Managers always get fired," a friend said. "If you become a scout, you'll have a job as long as you can see to drive."

That was all it took for Genovese to switch careers again.

While most scouts wanted sure-bets, he went to work for the San Francisco Giants searching for "sleepers" the other teams overlooked. That first year, he convinced the organization to sign a raw Bobby Bonds.

His list of discoveries grew to include other future all-stars — George Foster, Gary Matthews, Dave Kingman and Jack Clark — as well as solid pros such as Garry Maddox, Jim Barr and Randy Moffitt.

"Every day I'd get in the car and it was an adventure," he says. "I never knew what I was going to find."

Being a former player and manager helped. Genovese taught Foster to throw farther by changing his grip and transformed Mike Lieberthal from a decent shortstop into top-notch catcher.

Genovese decided to show Chili Davis to his bosses at the Giants' instructional league. Davis went on to play 19 years in the big leagues, including two stints with the California Angels. (Associated Press)

"One of the hardest things to do is evaluate amateur talent," says Fred Claire, former general manager of the Dodgers. "With all his experience, George could look at a young player just as he looked at a young Bobby Bonds or Jack Clark ... he was able to project."

By 1977, Genovese had adopted a new project, an athletic teen who came late to baseball. He decided to show Chili Davis to his bosses at the Giants' instructional league.

On the flight to Arizona, Davis mentioned experimenting with switch-hitting and wondered about developing that skill. Genovese did not say much.

But the next day, as the outfielder finished batting practice in front of Giants coaches, the scout spoke up: "No, he's not done. He's a switch-hitter."

Davis hesitated — it was a crazy idea — but couldn't walk away. Stepping back into the batter's box, he managed a few left-handed hits. It was the beginning of a career that would see him amass 350 home runs swinging from both sides of the plate.

"That's just George," says Davis, now a hitting coach for the Oakland Athletics. "I got to play 19 years in the big leagues and it all started with him."

The ball soars into center field and Puig, flashing his speed, makes the catch. It reminds Genovese of a young Jose Cardenal or maybe Roberto Clemente starting out in Puerto Rico.

"The kid is so gifted," he says of Puig.

The Dodgers have been his team since Claire brought him over in 1994. He watches them win handily over the Colorado Rockies, 6-1, remaining in his seat until the final out.

"Except for three years in the military, I've been in baseball my whole life," he says. "I feel very fortunate."

The game has changed. Free agency has shifted the balance of power and Genovese fears that huge salaries have spoiled some players. He hates that teams practice defense less often.

"I can see when mistakes are made," he says. "I can see when the game is not being played right."

But, at the end of the day, he would rather talk about the ways baseball has remained the same: The sights and smells of the stadium. A pitcher trying to sneak one more strike past a batter who desperately needs a hit. The roar of the crowd when a runner crosses home plate.

Every once in a while, someone asks him to evaluate a young prospect, maybe a grandson or a nephew. Like always, Genovese looks for quick hands at the plate or a burst of speed to first base.

"There's something about the game," he says. "You can't let go."

It's enough to make an old scout smile.

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.