MLB 1994 strike: Replacement players provided comic relief, farcical baseball

- Share via

The left-hander who works in the car-detailing business zipped a fastball into the mitt of the Home Depot department manager, and with that the Angels’ 1995 spring training camp was in full swing.

So read the lead to my first dispatch from Arizona in my first year as Angels beat writer for The Times, the start of a wacky six weeks of replacement-player ball that was a fantasy camp for participants, an embarrassment to coaches and executives who oversaw it and a gold mine of material for baseball writers.

The on-field action was often farcical, a continuous blooper reel featuring over-the-hill minor leaguers and fringe prospects willing to cross picket lines for a $5,000 signing bonus, $78 per diem and the eternal scorn of real big leaguers.

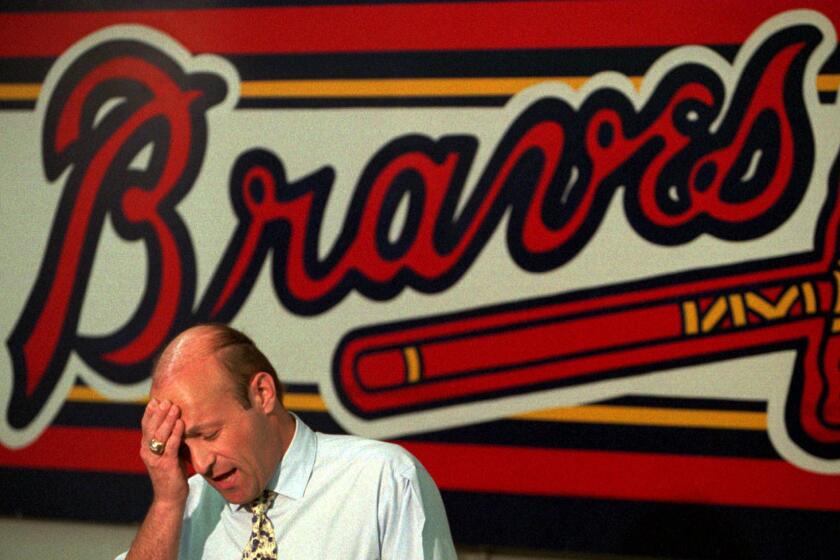

“Replacement-player baseball,” said Bill Bavasi, the Angels general manager from 1994-99, “was definitely a blight on a lot of our careers.”

Bavasi, who now works for the commissioner’s office in baseball and softball development, said he had no “fond” memories of the replacement-player spring, though one play stands out.

It came in the March 1 exhibition opener against Arizona State in Tempe Diablo Stadium, a game that attracted camera crews from “Good Morning America”, “ABC World News Tonight,” CNN and ESPN because it was the first time replacements had played in place of major leaguers in 83 years.

A Sun Devils player opened the game with a grounder to the Angels shortstop, who overthrew first base. The ball caromed off a concrete wall in foul territory and to the first baseman, who tagged out the runner before he could get back to the bag.

“And that was the first-ever replacement-player play, a 6-to-wall-to-3 tag-out,” Bavasi said with a laugh. “It was so nuts.”

Toronto GM Gord Ash refused to let his major league coaching staff work with replacement players. Detroit manager Sparky Anderson took an unpaid leave of absence that spring. Baltimore owner Peter Angelos refused to field a replacement team.

“Anyone who thinks the fans will accept replacement players as substitutes for the real thing,” Angelos said at the time, “is obviously suffering hallucinations.”

25th anniversary of baseball strike

A look back at the 1994 major league strike.

The shoddy play exposed the experiment for the charade it was and may have helped end a 7½-month strike that forced cancellation of the 1994 World Series. The replacements also brought much-needed comic relief to a sport that spent six months locked in a bitter labor dispute that threatened to destroy the game.

The Florida Marlins, in a desperate attempt to find a shortstop, tried a truck driver, a carpenter, a high school economics teacher, a junior varsity coach, a rookie league manager and two softball players at the position.

Among the Angels replacements was pitcher Bryan Smith, a former Dodgers minor leaguer on a leave of absence from his job as an FBI agent, and scrappy outfielder Chris Powell, a former Cal State Fullerton standout who was a slow-pitch softball teammate of mine in 1993-94.

Asked to predict the winner of a replacement World Series, Pittsburgh manager Jim Leyland said, “The team that can get the most guys out of the whirlpool and onto the field.”

The Cleveland Indians traded five players to the Cincinnati Reds for future considerations that spring.

“Cleveland definitely got the better end of the deal,” Reds manager Davey Johnson said. “They didn’t get anybody.”

Ron Rightnowar, a Milwaukee Brewers replacement player, threw a breaking ball completely behind Angels batter Randy Hood in one game.

“That’s what you call a real back-door slider,” Angels manager Marcel Lachemann said. “That was almost a back-pocket slider.”

The Angels’ low point was a game in which they committed four errors, ran into four outs on the bases, missed several cutoff men and threw a bevy of fat pitches in a 10-8 loss to the Brewers.

In attendance that day was Masayuki Kakefu, a former Japanese Central League star and aspiring manager who spent five days with the Angels observing practices and games.

What was Kakefu’s impression of the game?

“A lot of mental mistakes,” he said through an interpreter. “Boneheads.”

Angels replacement outfielder Jon Fishel, who helped Cal State Fullerton win the 1984 College World Series, was handcuffed in a game, but not by an inside fastball.

A Maricopa County sheriff’s deputy arrested Fishel during the national anthem on a warrant alleging he owed $67,000 in child support to a Phoenix-area woman who claimed Fishel was the father of her daughter.

Fishel spent 12 hours in a Phoenix jail, was released at 1:14 a.m. and was in uniform the next day. Fishel’s response to his incarceration proved prophetic, a perfect summation of how baseball feels about replacement players:

“I never want to go back there again.”

On the 25th anniversary of the most notorious work stoppage in sports, The Times takes a look a the impact the 1994 Major League Baseball strike had on the game, its players and its fans.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.