The defining moment of the Dodgers’ season went by almost completely unnoticed.

That’s because the importance of the moment wasn’t measured by what happened. Rather, it was measured by what didn’t happen.

When Mookie Betts returned to right field in mid-August, he didn’t complain. He didn’t brood. He didn’t stop playing like Mookie Betts.

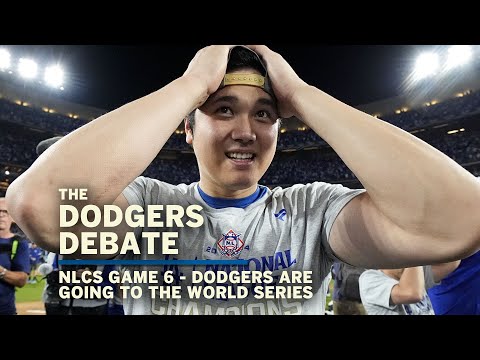

Instead of causing the kinds of problems that have derailed countless other teams with championship aspirations, Betts used his influence to create a culture of sacrifice that has become a trademark of the Dodgers, who will take on the New York Yankees in the World Series starting Friday.

“When guys like that do it,” manager Dave Roberts said, “everyone else has to fall in line, as far as whatever roles, wherever they hit in the order, if they play or start or don’t start.”

During the past few weeks, Dodgers players forfeited time with their families to spend more time with one another. Freddie Freeman played on a sprained ankle. Reliever Brent Honeywell threw live batting practice to slumping hitters.

Freeman said of Betts’ team-first mindset, “It just carries over to the rest of the team.”

In the retelling of this story, Dodgers officials say they never doubted that Betts would relinquish his place at shortstop and move back to right field. It would be more accurate to say they were hopeful.

Betts had always told them he would do whatever was best for the team. However, in his previous four years with the Dodgers, what he was asked to do generally coincided with what he wanted. In this case, they were about to ask him to do something he might not want to do.

Which would explain why, as Betts approached his return from a broken hand in early August, Roberts initially said he would remain the team’s shortstop.

A six-time Gold Glove Award winner in right field, Betts had an obvious affinity for playing the infield. The workaholic Betts had thrown himself into relearning a position he last played regularly in high school by taking grounders before every game. The broken hand in mid-June halted his progress.

By the time Betts was close to being activated from the injured list, the Dodgers knew they wanted him back in right field. At this point, Betts hadn’t played in seven weeks, costing him experience at his new position. The Dodgers had added infield depth in the likes of Tommy Edman and the since-departed Nick Ahmed. Miguel Rojas was also expected to return soon from an injury.

Shohei Ohtani suggested the Dodgers pay him only $2 million a year and defer the remainder of his annual $70-million salary. It was basically a blank check to fortify the roster.

Betts looked determined to remain the team’s shortstop, as he resumed fielding grounders as soon as he was medically cleared to do so. Team officials knew he could point to how he became the shortstop in the first place because they overestimated Gavin Lux’s ability to play the position. They knew he could point to how he already made a substantial sacrifice by switching positions in the lineup with Shohei Ohtani, who in his absence had taken over his preferred leadoff spot. They knew he could point to how he was, well, Mookie Betts.

“When you have a guy that has a name and just the accomplishments and talents about him, like someone like Mookie does, [and] he wants to be the leadoff hitter, he wants to play certain positions and you tell him he has to go somewhere else, you always worry about that causing conflict,” infielder Max Muncy said.

However, Muncy added, the players knew Betts wasn’t a typical superstar.

“There was never going to be any question from any of us about Mookie,” Muncy said. “We knew that he would do whatever it takes to help the team win. He’s proven that time and time again.”

Mookie Betts’ move to shortstop has sharpened his focus on the game, especially at the plate so far this season for the Dodgers.

Muncy raised another point.

“Him moving to the infield this year was about helping us win as much as anything,” Muncy said.

Unlike other players, Freeman noted, Betts just happened to be talented enough to play a new position.

“The man can do anything he wants,” Freeman said. “I think he’s one of the best athletes I’ve ever seen on the field. He’s one of the only people that could probably do what he’s done throughout the course of the year.”

The players were right. When Roberts addressed the situation, Betts agreed to the change.

“You want to win, that comes first,” Betts said at the time. “That’s all I care about.”

Complaining, Betts said, would have been “a very selfish thing.”

“That’s not who I am,” Betts said. “I’ve preached this from the very beginning, and I always will.”

He has lived up to his words. In addition to providing the Dodgers with a premium glove in right field, he has also shined as their No. 2 hitter, punishing opponents who elect to pitch around Ohtani.

When the Dodgers signed Betts to a 12-year, $365-million contract extension before the pandemic-shortened 2020 season, president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman said they were betting on Betts the person as much as they were Betts the player. Clearly, they made the right call. Their reward: a fourth World Series appearance in eight years.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.