For major league ballplayers, signature moments are part of the game

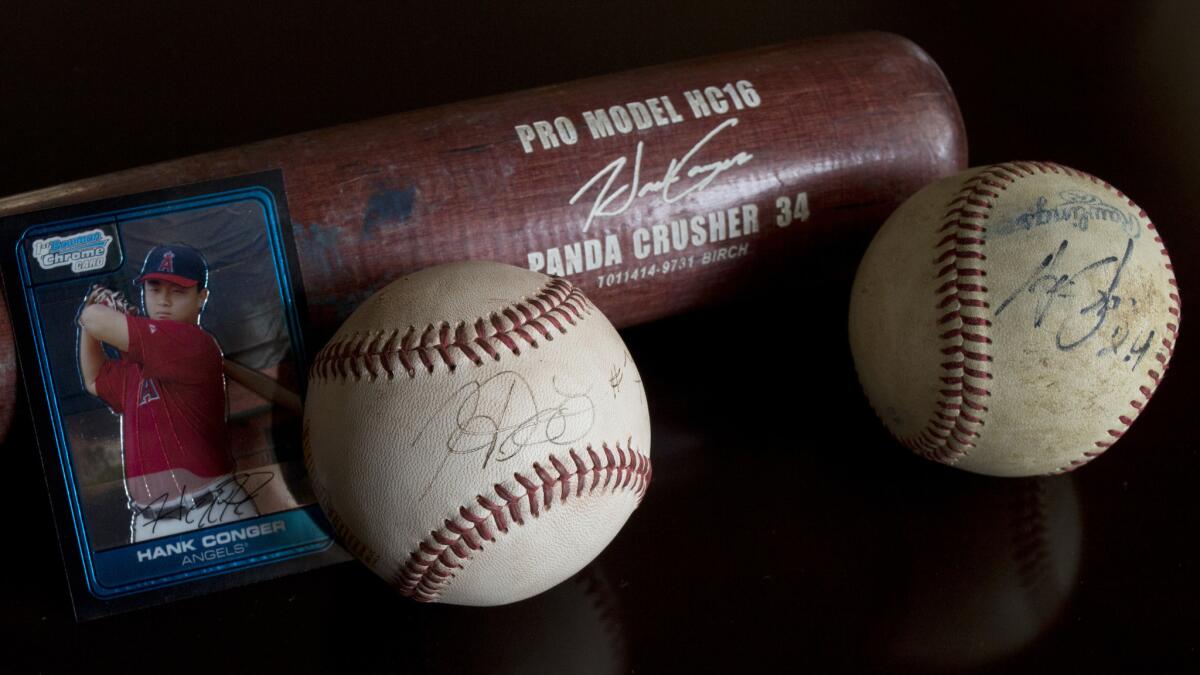

When Hank Conger was a child with dreams of playing professional baseball, he practiced his signature with one thought in mind: the more scribbles, the cooler the player.

And he planned on being very good and very cool.

So, by the time Conger reached the major leagues, his autograph was indecipherable. That is, until Torii Hunter watched one day as he signed.

“Man, what is that?” Conger, the Angels catcher, recalled Hunter saying.

“That’s how I’ve always signed my autograph,” Conger, then a rookie, replied.

“You know,” the veteran Hunter admonished, “if some kid picked up this baseball one day, you want to make sure they know who signed this ball. So make sure you sign neatly.”

Conger’s tangled thicket of loops clearly wasn’t up to standard, but his predicament wasn’t all that unusual.

Plenty of ballplayers have found the signature they worked on growing up — the one they lovingly honed on the sides of school work sheets and notebooks — doesn’t work for any number of reasons as their careers advance.

Some are illegible on a baseball, others just take too long to write. And so the signature of their dreams changes into something more mundane.

Dodgers second baseman Dee Gordon has gone through at least three iterations of his signature.

Growing up, Gordon would observe his father, longtime major league pitcher Tom Gordon, signing balls and jerseys, and he would try to do the same.

“Oh man,” Tom said. “This kid would write on everything.”

At 8, hoping one day he might be an NBA star, Gordon decided to try his signature on a round ball. He didn’t want to ruin his expensive basketballs, but plenty of his father’s baseballs were available.

Years later, Tom Gordon would display those baseballs — and other victims of his son’s active pen — in his home office. The penmanship looked different back then, before he perfected the “D” with the looping tail and refined the “G” he would later drop.

Doodling one day in college, Dee Gordon wrote his name as “D Style.” He liked the substance but the look wasn’t quite there. He wasn’t satisfied until he signed for a fan in Ogden, Utah, home of the Dodgers’ rookie-league team. By chance, the signature came out different: the large “D” flowed into an “S” with a matching tail and big, wide lettering in “Style.”

“And I was like, ‘Oh, that’s how I’m doing it,’” Gordon said. “I think I just visualized it.”

Gordon’s collectors are treated to a small piece of art. But many autographs go the way of Dodgers reliever Brian Wilson.

Wilson’s writing style in grammar school was very deliberate out of necessity. “When you start forging your parents’ name on your detention slips,” he said, “you become really good at it.”

His careful approach lasted until the first time Wilson, then playing for Louisiana State, had to sign about 50 dozen baseballs before the Southeastern Conference tournament. As he went on, the last few letters of each name began to disappear, until he wrote just “Bri Wil” with a few squiggles tacked on. More dropped off incrementally.

Now, Wilson just signs “BW.” “It’s about how quickly I can get something legible,” he said. “Sometimes not even legible.”

At least Wilson is consistent. Other ballplayers have been known to swap out autographs like shoes, discarding ones that feel too worn or opting for flashy looks one day and speed the next.

Mark McGwire used a neater signature for paid engagements and a scrawl at the ballpark. Angels outfielder Kole Calhoun said he has an “autograph” for fans and a “signature” for checks and legal documents. Conger sheepishly admits that, pressed for time, he reverts to a sloppier form.

Each player develops his own style and rules about signing, and it’s always been that way, said Joe Orlando, president of PSA/DNA, a company that authenticates collectibles.

Mickey Mantle gradually changed his signature from the plain text he developed at home in rural Oklahoma to one with flamboyant loops when he became a New York City-based star. Willie Mays’ autograph in some incarnations looked like “Tommy Hoop,” leaving some people to wonder if he wasn’t a frustrated basketball player.

Baseball’s popularity and financial clout has also prompted changes in autographs over the years.

For example, before the 1980s memorabilia was not big business, which meant players were not hounded as much and therefore could spend more time writing their names at the ballpark. But then the collectibles market exploded and signatures became a lucrative source of income. In many cases, former stars made more money signing in retirement than they had earned when they were playing. Their name became their paycheck, so they took care to be neat and consistent with their signatures.

Today, players are less accessible and even reserves make big money — the minimum major league salary this season is $500,000 — so they have little incentive to keep an appealing autograph.

Consider Angels star Mike Trout and Mantle, with whom his baseball skills are often compared. Whereas Mantle’s autograph was a careful display of interlocking loops, Trout’s has been simplified to two recognizable letters — M and T — with what is basically a line scratched after each.

“It’s remarkable the difference between a Mickey Mantle signature and a Mike Trout signature,” Orlando said.

Trout signed a six-year, $144.5-million contract extension before the season and is among the game’s biggest attractions. He is generous with his time with fans, but his strategy is clear when it comes to autographs: sign as many as possible in as little time as possible. Before one recent game, he scratched out his name in two seconds per baseball, without fail.

Trout doesn’t remember much about how his autograph evolved. His signature has been in demand for quite some time — he said he started signing for fans in high school.

The player whose signature is unchanged since childhood is extremely rare.

Angels Manager Mike Scioscia said his signature is the product of his Catholic schooling outside Philadelphia. He wouldn’t want to upset the nuns with poor penmanship.

Over the years, his autograph has developed its own sort of magic. The “M” has too many humps, which form three convincing finger holes. Scioscia, a former catcher, adds a looping curlicue above the letter with another marking, as if for a thumb. Flipped over, it looks almost like, well, a catcher’s mitt.

“Does it?” Scioscia said before a recent game. He looked at the letter as if it were cuneiform.

“I never even . . .” Scioscia’s voice trailed off. He grabbed a pen and scribbled. Then he examined again.

“Yeah maybe it does,” he said. “That is absolutely, one hundred — one million — percent not by design.

“I just sign my name.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.