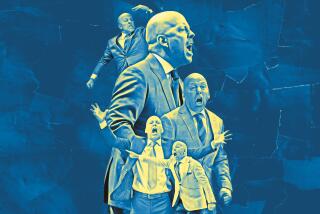

Hall of Famer Tony Gwynn discusses his struggles with cancer

The most famous smile in San Diego couldn’t be seen over the phone line, but it could be heard.

It could be heard when Tony Gwynn light-heartedly talked about how much easier it was to hit a baseball than fight for his life. Or when he spoke about coaching again, or his son’s move to the Dodgers.

Gwynn sounded upbeat. Sometimes, he even laughed.

Tony Gwynn sounded like Tony Gwynn.

“Things are about back to normal,” said the most beloved player in the history of the San Diego Padres.

Earlier this week, Gwynn, 50, returned to his office at San Diego State, where he has been the head baseball coach for the past decade — and was able to do so with a smile on his face.

Gwynn’s players haven’t seen much of the Hall of Famer since he was diagnosed in August with cancer in his parotid, a salivary gland along the jaw. Even on the days this winter when he visited the baseball field that bears his name, the players didn’t see the jovial man they knew.

Surgery to remove a tumor resulted in paralysis in the right side of his face, compromising his ability to smile or laugh. He couldn’t blink his right eye. Radiation and chemotherapy left him so weak that he had to use a walker to get around. He estimated that he lost about 80 pounds from his 300-plus-pound frame.

Usually, Gwynn “has a glow about him,” senior outfielder Pat Colwell said. “He jokes around; he has a huge smile.

“That just wasn’t there.”

As recently as a week ago, junior outfielder Brandon Meredith said the Aztecs were “preparing for the worst” — that Gwynn would miss the entire season.

But Gwynn said he is optimistic about his recovery. He completed treatment in December and has started an exercise program. He was healthy enough to undergo an operation last week to fix a disk problem that had bothered him for the last year and a half.

And when the Aztecs open their season Feb. 18 against Winthrop, he plans to be on the bench. He’s even hopeful he can be at their alumni game on Saturday.

He said he also intends to continue broadcasting Padres games on local television.

“I haven’t had any setbacks whatsoever,” Gwynn said. “I’m getting control of my face again.”

While Gwynn said he doesn’t consider himself cured — he has follow-up appointments scheduled — his progress has afforded him the luxury of reflecting on the last six months and asking himself, “How did I get through all of that?”

Gwynn said he wasn’t concerned when he required surgery in August to remove a tumor from his parotid. He had undergone two similar procedures in the past; both times, the tumor was benign.

Not this time.

Nothing in life had prepared him for that kind of news. Gwynn demonstrated unusual resolve as an athlete, working himself into a player who won eight National League batting titles and hit .338 over a 20-year career that was spent entirely with the Padres. But his battle with cancer required more than resolve.

“Baseball-wise, I knew if I put in the work I was going to get results,” Gwynn said. “Not knowing how it’s going to turn out, that’s the hard part. After being in control 20 years of your career and in nine years of coaching, now you ain’t in control anymore.”

Gwynn said he wasn’t sure he would even be able to smile or laugh again.

But he received constant encouragement from his wife, Alicia, who drove him to daily treatment sessions.

“She kept telling me, ‘Everything’s going to be fine,’” he said.

Gwynn quit chewing tobacco, thinking the habit might have been responsible for his illness.

Gwynn was largely absent from fall practice, but his players assumed his back problems were the reason.

Assistant coach Mark Martinez, who was left in charge of the team, was among the few people who knew about Gwynn’s condition.

“When he told me, my body went numb,” Martinez said. “You don’t know what to do.”

Other than not tell anyone.

“He’s telling me that in confidence,” Martinez said.

When players asked Martinez where their coach was, he told them, “His back’s hurt” — true, but only part of the story.

Meredith, a preseason All-American, was particularly affected. Gwynn used to work with him extensively on his hitting. He also taught him how to play the outfield.

“A couple times throughout the fall, I felt my swing wasn’t where it had to be,” Meredith said. “I didn’t have that Tony Gwynn figure to help me out.”

Come October, Gwynn felt he had to inform his team why he wasn’t around. Martinez called a meeting in the locker room.

“He choked up when he started to tell us,” Colwell said.

Soon, almost everyone in the locker room was crying.

“One of the hardest things I’ve seen a man do,” Martinez said.

The Aztecs adjusted.

When potential recruits visited the school, Martinez made sure they did so on the rare days he knew Gwynn would be on campus.

While the blow to the team’s psyche was somewhat diminished by the fact that many of the players had never played for Gwynn — 17 of the 33 are freshmen — veterans such as Colwell and Meredith said their coach’s situation has served as motivation.

Martinez said the players should know what to look for to get an idea of how they’re doing.

“If we’re doing well, Coach Gwynn will flash that smile,” Martinez said. “That will make them feel really good.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.