Q&A: Author of Kobe Bryant book ‘The Rise’ gives his insights

- Share via

Hey, everyone, it’s Lakers beat writer Dan Woike of the L.A. Times. Welcome to this week’s edition of the newsletter. I’m writing this after a nice morning walk through the monuments in Washington, D.C. — a refreshing change of pace after covering the monumental disappointment that’s been this Lakers season.

We’ve spilled a ton of ink on this season, and we’ll spill a lot more on why the future is still sort of bleak. So in the meantime, I wanted to take a look back this week with someone who just immersed himself in the past of a Lakers icon.

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

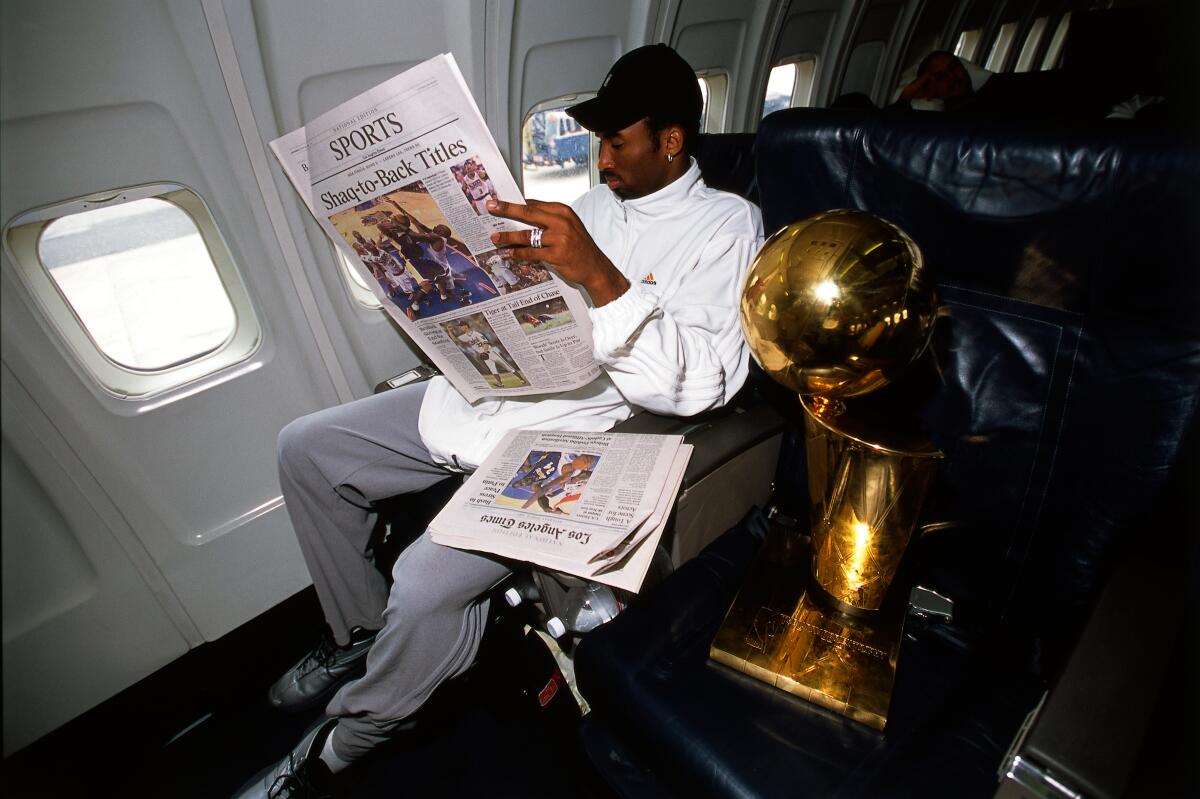

Here’s my chat with Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Mike Sielski, author of “The Rise: Kobe Bryant and the Pursuit of Immortality.”

Kobe is so closely associated with Los Angeles from his time with the Lakers, but how connected are the people of Philadelphia with him? How connected did he stay to Philly?

The smaller group of people who knew him at or through his early life in the Philly basketball scene and at Lower Merion High School — coaches, teammates, classmates, competitors, friends — obviously have felt and still feel a strong connection to him. As for the rest of the Philadelphia area, particularly the city itself, its relationship with Kobe has always been pretty fraught. Kobe always thought himself beyond Philadelphia, and around here, there’s no greater sin an athlete can commit, whether he/she is from this area or not, than thinking you’re better than Philadelphia. He wanted to play for the Lakers when he was a kid. He didn’t aspire to play for the Sixers, not really. Plus, technically, he wasn’t from Philly; he was from a suburb just outside Philly. And, of course, there was the whole “I’m gonna cut your hearts out” thing in the 2001 NBA Finals. But as Kobe’s career wound down, and certainly after his death, Philadelphia warmed to him more. And the irony of Philly’s general dislike for Kobe is that, because he was so competitive and so driven to be great, he would have been a god here if he had played for the Sixers. No athlete better embodied what Philly wants from its sports stars, and it’s that very quality that made him a relative villain here. It’s natural: The quality that attracts us to a friend repels us from a foe.

In reporting the book, what was the biggest misconception that you discovered?

I don’t think people appreciate how insecure Kobe was, how he groped around for his identity, during his early life. People who are intimately familiar with his career probably have some sense of it, especially from his first few years with the Lakers, but I suspect the popularity of the “Mamba Mentality” has led most people to think Kobe was supremely confident his entire life. When it came to basketball, he was. When it came to most other aspects of his adolescence, he wasn’t. He played baseball in eighth grade. He joined the Student Voice, Lower Merion’s Black student union, not long after entering high school. He had a quasi-girlfriend in high school but didn’t really date; she’d come over on Friday nights to watch basketball videos with him and his family. I have a line in the book: “He could relate, and he could not relate.” That sums him up well, I think. He was trying to figure out who he was and where he fit in.

Before you worked on the book, did you have a favorite Kobe story?

I did, and it ended up in the book’s afterword. In 2007, I heard a rumor that Kobe was thinking about ending his career in Philly with the Sixers. So when the Lakers came to town, I asked him about it in the locker room after the game. He paused for a while. “That would be nice,” he said. “In high school, that’s all I thought about.” But I knew that really wasn’t true. He didn’t dream of playing for the Sixers. He dreamed of playing for the Lakers. And here it was, three years after Aurora, Colo., and Kobe was still conscientious about his image, about rehabilitating it, and he was clearly weighing his answer: What is the right thing to say here? What do I really think, and what do people want to hear? There is always going to be some mystery at the heart of Kobe, and I think that anecdote captures at least some of it.

After working on it, what’s your favorite Kobe story?

So Kobe had a friend — Anthony Gilbert, who has gone on to write for SLAM Magazine and be a familiar face to NBA players — who was a couple of years older than he was. When Kobe was 14, 15, 16 years old, the two of them would drive around to playgrounds and courts in and around Philly to play ball … but a particular kind of ball. Anthony had two jobs when they would play. One, he would rebound for Kobe as Kobe shot threes, dunked, and worked on his footwork. Two, he would yell at Kobe: “YOU’RE SOFT. … YOU GO TO A WHITE SCHOOL. … YOU COULDN’T PLAY IN THE PUBLIC LEAGUE.” Kobe asked him to do this, wanted him to do this. He believed it would gird him for the trash-talking he was already hearing and would hear through high school and his career in the NBA. He was donning emotional armor.

Find me another 15-year-old kid who thinks like that.

Who was someone you discovered had a major impact on Kobe’s path — maybe someone Laker fans don’t know about.

Katrina Christmas was a librarian at Lower Merion High School and the faculty adviser to the Student Voice. Kobe confided in her quite a bit during his high school years, especially about his identities, insecurities and challenges as a Black teenager [one who had lived in Italy for eight years] growing up in a tiny suburb of Philadelphia. Kobe would talk to her about life, girls, pretty much anything. They had quite a bond.

Have you heard from anyone with the family about the book?

I did speak with Kobe’s cousin John Cox for “The Rise,” and John was great, open and helpful. But I have not heard from Vanessa Bryant or from Joe and Pam Bryant. I sent Kobe’s parents and sisters a letter and samples of my writing, asking for their cooperation when I began my research and reporting for the book. I never heard from them directly, but a couple of family friends told me Joe and Pam were aware I was doing the book. I contacted someone who represented Vanessa back when I started the project, and I was told that, while Vanessa declined to speak to me for the book, she wouldn’t stand in my way. That was fine with me.

Going back to him declaring for the draft, what were the realistic expectations for him? Were people mad that he landed with the Lakers?

It was difficult to gauge what expectations were for Kobe then, because the range of opinions on him went from Jerry West’s belief that he was the best player in the draft to general skepticism that a willowy 6-foot-6 guard could make the jump straight from high school to the NBA. The Sixers had the No. 1 pick, considered taking him, and decided Allen Iverson was the scorer they needed and the safer choice. John Nash, the general manager of the New Jersey Nets at the time, loved Kobe, but Kobe and his agent, Arn Tellem, head-faked John Calipari and the Nets out of taking Kobe by threatening that Kobe would sooner play overseas than in the swamps of Jersey. As for the anger toward Kobe landing with the Lakers, it was directed at him and Tellem more for their manipulation of the situation, the measures they took to ensure that Kobe ended up in L.A. How dare a teenager do this! Who does he think he is? It’s pretty ridiculous in retrospect, because a player taking control of his future is such a common occurrence today.

::

I really appreciated the chat with Mike, a terrific columnist and author of a terrific book. Maybe, if someone thinks up a fun contest, we can give away a few copies here. Let me know if you have a contest idea we should try, and we’ll get the lawyers involved.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Song of the week

“School Spirit” by Kanye West

Happy March Madness, everyone. I wanted to find a song that not only captured college but also something I really enjoyed listening to in college. I remember making long drives home, playing Kanye West’s “The College Dropout” on repeat, thinking I’d never heard anything quite like it. I do, in fact, miss the old Kanye. This track qualifies as a deep cut from an album that had so many hits, but it references Norah Jones and the Cheesecake Factory, so I thought I’d share.

In case you missed it

The Lakers’ latest struggles were the talk of the Timberwolves

Lakers-Raptors takeaways: sluggish offense, late rally and yet another loss

LeBron James hits another milestone as the defenseless Lakers lose by 29 to the Suns

The Lakers’ Talen Horton-Tucker plays big off the bench in a win over the Wizards

LeBron James’ 50 points push the Lakers to victory over the Wizards

The Lakers vs. the Celtics is bigger than basketball. Here’s the truth behind the NBA’s top rivalry

Until next time...

As always, pass along your thoughts to me at daniel.woike@latimes.com, and please consider subscribing if you like our work!

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.