Doping bans leave weightlifting with a heavy burden to bear

- Share via

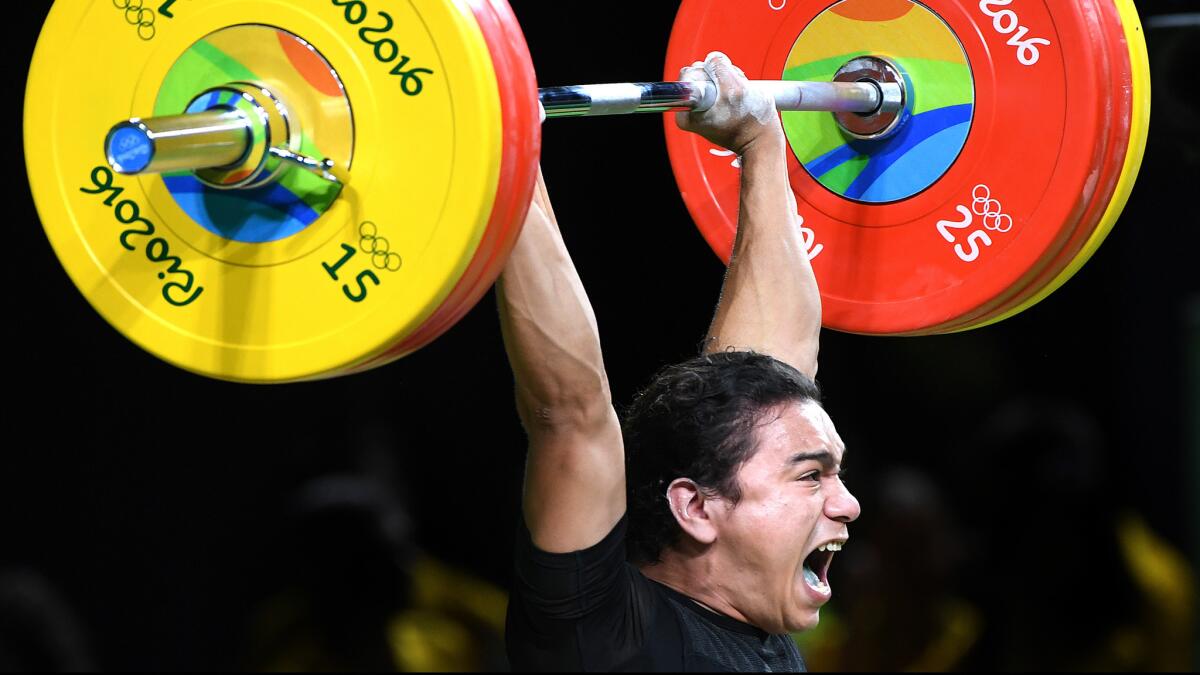

Reporting from Rio de Janeiro — Colombia’s Oscar Figueroa lifted 701 total pounds Monday night, which was good enough to win the gold medal in weightlifting at 136 pounds.

But even Figueroa may not be strong enough to lift his sport out of the muck of a doping controversy that has tarnished these Olympics and clouded weightlifting’s future, at least in the short-term.

Many of the sport’s best teams and athletes didn’t come to Rio after they were suspended for cheating. The Russian and Bulgarian teams were banned completely; Kazakhstan and Belarus are appealing similar one-year bans.

Athletes from nearly 10 other countries — among them double gold-medalist Ilya Ilyin of Kazakhstan, one of the sports biggest names — were told to stay home and then hours before Friday’s opening ceremony yet another lifter, Antonis Martasidis of Cyprus, failed a drug test and was expelled as well.

All of which means one of two things: either the sport is so riddled with cheaters it’s impossible to know who’s clean and who isn’t. Or the International Weightlifting Federation’s new anti-doping policies are working.

Phil Andrews, the British-born chief executive of USA Weightlifting, prefers the second explanation because accepting the first would be conceding that weightlifting, once a premier Olympic sport, is now the Games’ dirtiest.

“This has been a very tough few weeks for our sport. It’s been a wakeup call,” he said. “It’s a clear policy of ‘OK this is bad. Now what do we do?’

“We’ve taken some firm action. We need to take more action.”

This is not the first time weightlifting has found itself at the center of a doping controversy. The use of performance-enhancing substances was so prevalent in the 1990s, the IWF restructured its weight classes in 1993 and again in 1998 to erase questionable world and Olympic records.

In some ways, the scope of the current scandal suggests things really haven’t changed over the last two decades.

According to the IWF website 70 athletes were sanctioned for doping last year alone, including 24 of the nearly 200 athletes who were tested at last year’s world championships in Houston. Retests of urine samples from the last two Olympics produced 20 more positive results.

But all those taken together don’t match the 117 failed tests from Russian lifters that were hidden by a Moscow laboratory over a four-year period, according to the independent McLaren report issued last month.

What has changed over the last two decades, however, is the public’s perception of weightlifting, with many now believing the sport may be beyond reform. When the Bulgarian team was sent home from the 2000 Olympics following a positive drug test, for example, that was considered a national embarrassment. But when Bulgaria was banned from this summer’s Games, sports commentators there turned it into a joke, saying the country’s doping team had been caught weightlifting.

“The Olympics has the [motto] ‘faster, higher, stronger,’ ” said Andrews, one of the sports most passionate advocates for reform. “We’re the stronger. As a result anabolic agents will make a huge difference in the sport of weightlifting.

“Unfortunately there’s countries who have made it clear that they will do, effectively, anything to win.”

And though Andrews insists the U.S. isn’t part of that group — “we can’t cheat because we have morals and values,” he said — Sarah Robles, one of four U.S. weightlifters in Rio, was given a two-year ban by the IWF in 2013 after testing positive for three banned substances.

That means for the time being athletes such as Mattie Rogers, who was an alternate on the U.S. team in Rio, will have to accept the possibility that some of the lifters they’re competing against are cheating.

“I know I’ve gotten the drug accusations,” conceded Rogers, a fresh-faced 20-year-old from Florida who holds three national records and said she’s never used a banned substance.

“I don’t know if it can ever be fixed completely. For a while, until they can clean it up, if it’s possible to clean it all up, that’s just going to be how it is.”

Andrews not only believes it’s possible, he believes it’s already happening, pointing to the Olympic bans as proof.

The IWF has enacted anti-doping policies that are among the strongest of any Olympic sport, he said, ones that call for more testing of more athletes, both in and out of competition, as well as stronger sanctions for those who test positive.

And there is no statute of limitations on penalties for a failed test since the IWF is now preserving urine samples for retesting as the technology to detect banned substances improves.

“If you do it, you’re going to get found out,” he said. “You may not get found out today but you’re going to get found out when testing improve[s].

“This is being taken very seriously. Enough is enough.”

kevin.baxter@latimes.com

Twitter: @kbaxter11

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.