PARIS — The swimming competition at the 2024 Summer Games will conclude with four medal races Sunday, but that won’t quash a geopolitical tug-of-war that has erupted at the pool.

An ongoing scandal involving Chinese swimmers and a slew of failed drug tests has U.S. authorities openly bickering with their international counterparts and with Olympic leadership. Salt Lake City has been dragged into the mess too.

An American official described it as “playing a game of ping-pong with media bullets.”

It all began last spring when the New York Times and German broadcaster ARD reported that 23 members of the Chinese swim team had failed drug tests in early 2021 but were allowed to continue competing, with several winning medals at the Tokyo Games.

Eleven of those athletes — including star Zhang Yufei — are on China’s roster in Paris. As U.S. swimmer Katie Ledecky told reporters: “It’s disappointing.”

The rhetoric has been far sharper among officials talking about lawsuits and “scare tactics.” The International Olympic Committee has threatened to take back the 2034 Winter Games it just awarded to Salt Lake City.

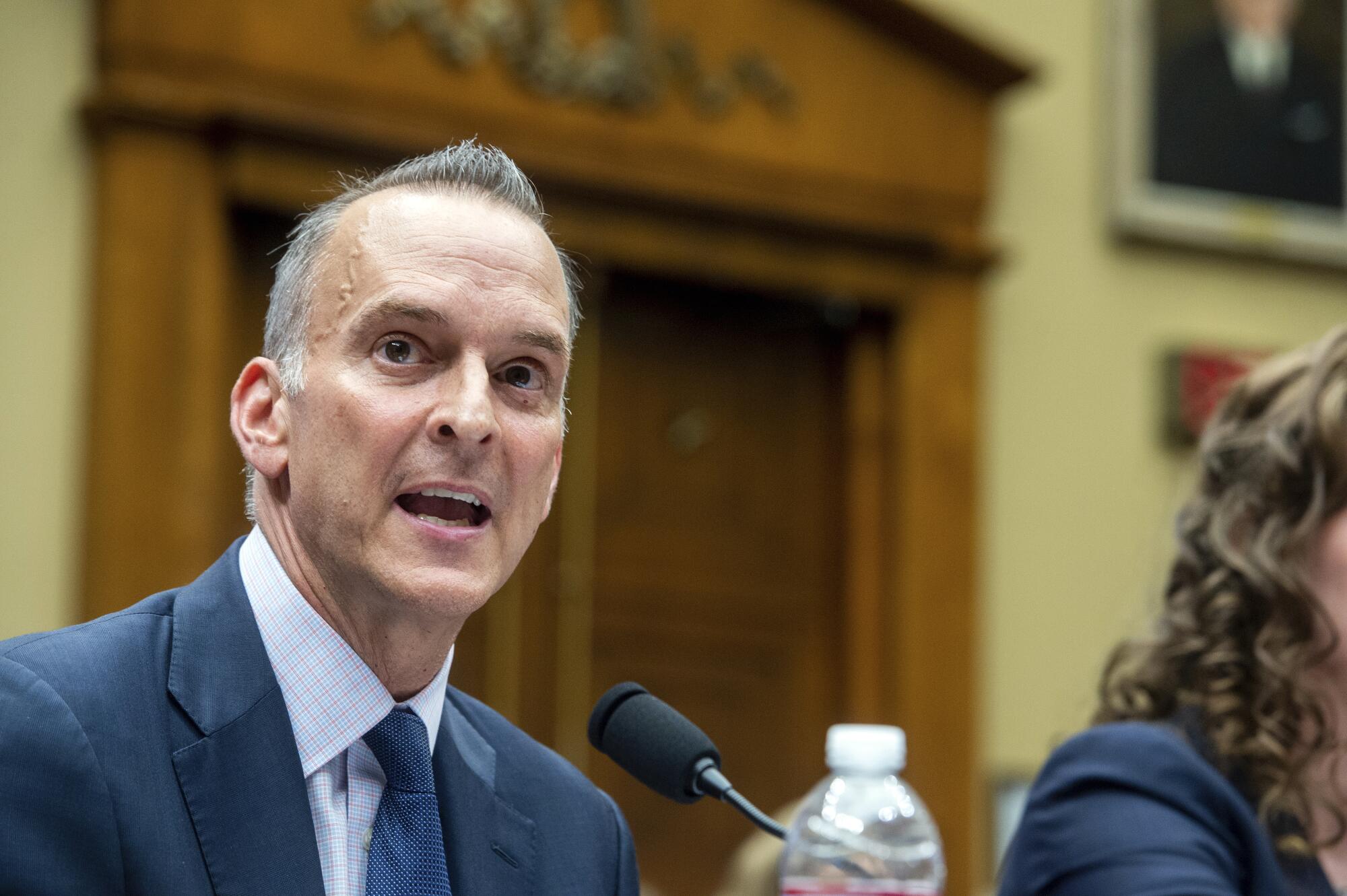

“As soon as one side comes out with a statement, the other side comes out with a statement,” said Gene Sykes, chairman of the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee. “They have not been shy about throwing rocks at each other.”

Recent events at La Defense Arena, the swimming venue in Paris, have underscored chaos in the anti-doping world.

International protocol entrusts each nation with policing its own athletes, so it was China’s anti-doping agency that initially tested the swimmers, finding evidence of trimetazidine, a medication that increases blood flow to the heart.

The Chinese blamed tainted hotel food but did not immediately report the positive results, as required. When finally informed months later, the World Anti-Doping Agency accepted China’s explanation.

Much of the sports world reacted angrily when the situation came to light. The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency issued a 16-page response.

“Our hearts ache for the athletes from the countries who were impacted by this potential cover-up,” USADA Chief Executive Travis Tygart stated. “They have been deeply and painfully betrayed by the system.”

Thus began the global tit-for-tat.

WADA threatened to sue Tygart, then announced an independent Swiss prosecutor had found no bias in their handling of the case. U.S. lawmakers soon weighed in, asking the Justice Department and FBI to launch an investigation under the Rodchenkov Act, which claims jurisdiction over international sports events that include American athletes.

Tygart kept up the heat, saying: “WADA is just a sport lapdog and clean athletes have little chance.”

At an IOC session in Paris before the opening ceremony, members voted to award the 2034 Games to Salt Lake City but included a provision that allows for host cities to have their contracts terminated if they question WADA’s “supreme authority.”

At that point, Sykes played peacemaker, saying: “What we want to do is cool the tempers and find a way for these organizations to constructively work better together.”

The 31 Chinese swimmers in Paris have been tested, on average, 21 times this year, the international swimming federation says. That is five times more often than the Australians and three times more often than the Americans.

Chinese swimmer Qin Haiyang, who holds the world record in the men’s 200-meter breaststroke, has used social media to claim the scandal is a “trick” to “disrupt our preparation rhythm and destroy our psychological defense.”

“This proves that the European and American teams feel threatened by the performances of the Chinese team in recent years,” he wrote.

But, on Tuesday, the New York Times reported a separate incident in which two Chinese swimmers tested positive in 2022.

WADA quickly issued a statement saying the swimmers were among a group of athletes who had ingested contaminated meat and that all were provisionally suspended for as long as a year until their cases were resolved.

Tygart was not mollified, saying: “China seemingly has the playbook to compete under a different set of rules tilting the field in their favor.”

The persistent rancor is taking a toll on Zhang. With two bronze medals in the first week of the Paris Olympics, she did not see much hope of the storm abating.

“I’m very worried that my good friends look at me with colored eyes and they do not want to compete with me or watch my races,” she said. “I am more worried that the French people do not think the Chinese deserve to stand on this stage.”

Katie Ledecky embraces expectations to dominate the 1,500-meter freestyle race, but she says it isn’t easy. She celebrated winning the race Wednesday.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.