Column: Where’s the energy? Staples Center is a strange, cold place without fans

- Share via

It’s a midweek winter night outside Staples Center, where the hum of life has been replaced by the dirge of desolation.

The plazas are empty. The ticket windows are boarded up. The statues are shrouded by tarp-covered fences. The dazzling bright lights of adjacent L.A. Live are on, but it seems like nobody’s home.

Two lonely souls stroll down Chick Hearn Court, a vacant asphalt stretch covered in swirling tire tracks from where unfettered drivers have been doing doughnuts.

The men are approached by a reporter asking what used to be an easy question.

“Hey, did you know the defending NBA champion Los Angeles Lakers are playing the San Antonio Spurs inside that building next to you?”

“Where?”

“Right here.”

“When?”

“Right now.”

“Right now?”

“It’s the third quarter.”

“That’s crazy, man.”

With that, the surprised visitors quickly turn and walk briskly away as if exiting a haunted house. They refuse to give their names, but their reaction is certifiably valid.

This is crazy, man.

The Lakers, Clippers and Kings are spending their seasons in what is essentially a ghost town, this country’s most vibrant sports center hosting games that are silent and barren.

Sadly it’s old news that the pandemic has stripped Los Angeles sports venues of their fans, but it’s particularly sobering news when it happens at the entertainment capital that is Staples. And it’s downright startling news when it happens to those champion entertainers known as the Lakers.

While their trademark low lighting makes their home games look relatively normal on television, witnessing one in person is an entirely abnormal experience.

Meet the No-Show Time Lakers.

“It’s so weird, man,” Lakers forward Jared Dudley said. “It’s literally lifeless.”

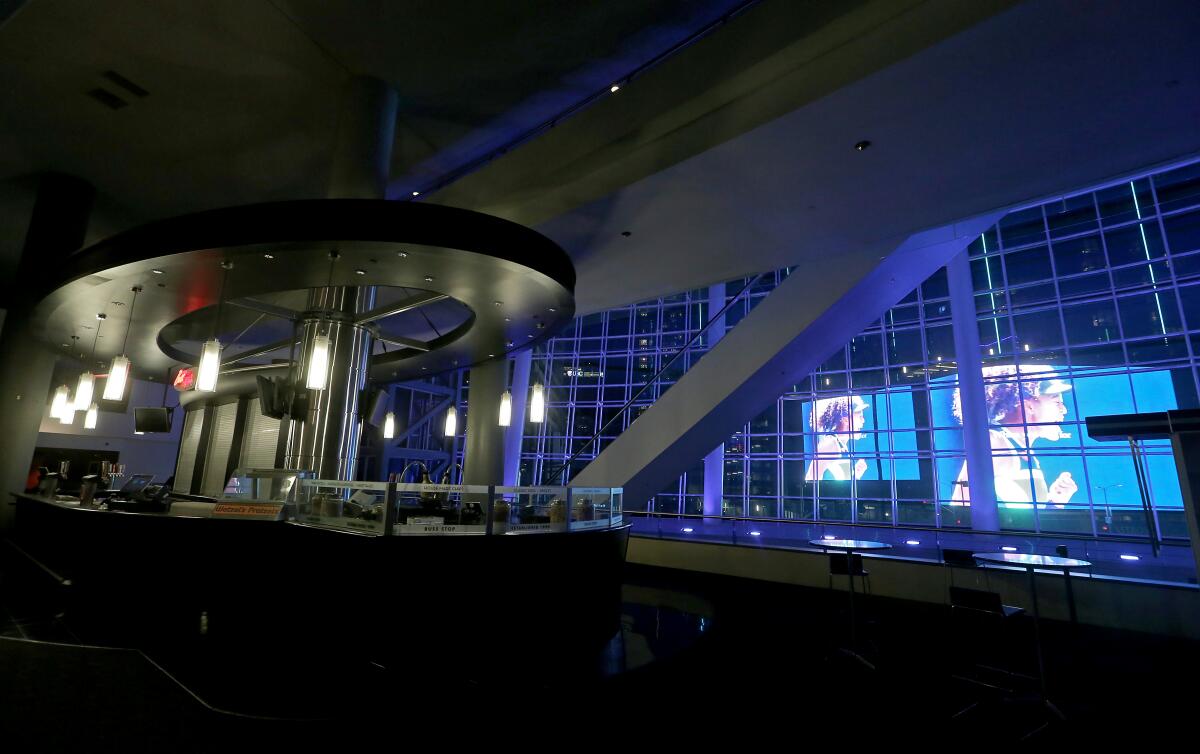

The weirdness begins the minute you walk into the mostly deserted building and feel the chill.

It’s cold. It’s so cold that at least one media member is wearing a ski cap and some workers at the scorers’ table are wearing jackets. No fans means no body heat to counteract the ice that is several inches under the hardwood, and that means cold.

“Those 18,000 fans provide so much heat, look at videos from last year’s opening night, before the game, LeBron [James] is standing at the foul line sweating,” Dudley said. “This year, no sweat.”

It’s eerie. It’s as eerie as an abandoned warehouse. The vacant concourses feel like what mycolleague Dan Woike perfectly described as a shopping mall after closing. They are sparkling clean and totally uninhabited.

“It’s a big deal for us personally to bring super-tough energy to the gym, pumping the guys up, screaming, running on the court, talking nonstop.”

— Jared Dudley, Lakers forward, on trying to bring energy to the game

Maintenance workers empty trash cans that have long been empty and scrub tabletops that haven’t been touched in months. Shuttered concession stands sit amid dozens of televisions that are tuned to the game but completely unwatched.

Once inside the event space, the court area looks like the setting for a scrimmage. There are no courtside seats, not even a place saved for Jack or Denzel. There are no baseline seats, not even a colorful reminder of Jimmy Goldstein. The players from both teams fill one sideline, socially distanced and each with their own giant orange cooler, while the other sideline sits empty. There are no Laker Girls. The national anthem singer appears on video.

Only one thing feels right, only one thing makes it feel like a Lakers game at Staples Center, a soothing voice that comforts amid the chill. Yes, valiantly providing a human soundtrack to this ghost town is venerable public address announcer Lawrence Tanter.

“A lot of people ask me, what’s the vibe, and I haven’t quite got a handle on it yet,” Tanter said. “I just know, it’s different, man. Real different.”

Of course he’s here. Even in these oddest of times, it wouldn’t be a Lakers home game without him. In his 38th season, he’s become as much a part of their homecourt aura as Randy Newman.

“L.T. has to be there, he is such an important part of the fabric of our brand,” said Tim Harris, Lakers president of business operations. “Under the current conditions, he’s as important as the court, the lights, the banners, everything. He makes the players feel like they’re home.”

Tanter’s voice was recorded for use last fall during Lakers games in the Florida bubble. This season Staples Center is thankfully filled with the wonderfully baritone live version.

“And now, celebrating their 61st year in Southern California, 73rd year in the NBA, the franchise with 17 NBA titles, the home team, the defending NBA world champions, YOUR Los Angeles Lakers!”

Except this season Tanter is speaking from behind a mask, sitting alone at the end of the scorers’ table, and introducing the teams to rows and rows of empty and tarp-covered seats.

“I hope I’m doing a good job, but I don’t know,” Tanter said. “There’s nobody around to tell me.”

He’s doing a spectacular job, enunciating normalcy in an upside-down world. Tanter steadfastly announces as if there’s a full house, a regular game, an ordinary night. His voice rises with each great Lakers play even though nobody is cheering. His voice levels with each opponent’s achievement even though there are no boos. He prefaces some of his announcements with “Ladies and gentlemen” even though he’s talking to neither.

“I have an obligation to be a public address announcer whether there’s 19,000 people or 19,” he said.

Or, zero. The nightly attendance at what would have been the hottest ticket in all of sports is zero. Think about that. The Lakers can’t avoid that fact as they try to re-create their game magic out of thin air.

“Here, you can hear a quarter drop.”

— Jared Dudley on playing in an empty Staples Center

“We’re trying to dissipate that empty arena awkwardness for all the players,” Harris said. “But we’re also trying not to over-create atmosphere. We want to make them feel at home while keeping the focus on the game.”

It’s a fine line the Lakers walk carefully.

A recorded organ leads cheers that are never heard. A spotlight dances among a crowd that doesn’t exist. Music plays even though there are no fans to dance. But there are no cardboard spectators. The canned cheering is so muted the players barely hear it. And, unlike in other places, under no circumstances do they play recorded booing or chants of “airball.”

This is where Dudley and all the Lakers reserves come in. By necessity, they are the most animated group in the building. From the bench they wildly celebrate, challenge, talk trash, anything to build the energy in a building that has none.

“It’s a big deal for us personally to bring super-tough energy to the gym, pumping the guys up, screaming, running on the court, talking nonstop,” Dudley said. “We have to re-create what is missing in the stands.”

Still, the building feels huge, and the emptiness is pervasive. When James fights for a driving layup and a foul, there is no excited sound upon which to build the momentum. When the other team is hitting threes and going on a run, there is no loud unrest that can change the narrative.

The players say that last fall’s bubble felt intimate and compact and was easily filled with their own energy. They say Staples Center is just too darn big and cavernous and void of life for any sort of charge.

“Here, you can hear a quarter drop,” Dudley said.

The silence is particularly overwhelming after the game ends. The moment the players leave the court, the music stops. The floor and its surroundings are quickly emptied, the only sound being the quiet whoosh of the giant mops being pushed down the hardwood. Within five minutes of the final buzzer, it’s like the game never happened.

At the end of this midweek winter night inside Staples Center, Tanter slowly packs up his paperwork, straightens his jacket, adjusts his newsboy cap and walks alone through a quiet tunnel to his car. He would normally stick around to announce the players’ final statistics. He has temporarily ditched the postgame tradition upon realizing its futility.

“There’s nobody listening,” he said. “There’s nobody there.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.