Same old, same old.

That’s the feeling I had this past week when I heard about “race-norming,” which curves the cognitive test scores of NFL players who are Black, assuming they have a lower level of intellect. I wasn’t familiar with the specific term, but I wasn’t at all surprised.

It’s kind of like when Dez Bryant made that catch against the Green Bay Packers in the playoffs, the one that was ruled a non-catch on the field. We all saw it. The whole world knew it was a catch. But it took the NFL a few years to come out and say, “Oh, yes, it was a catch after all.”

Gee, thanks. It was another slap in the face.

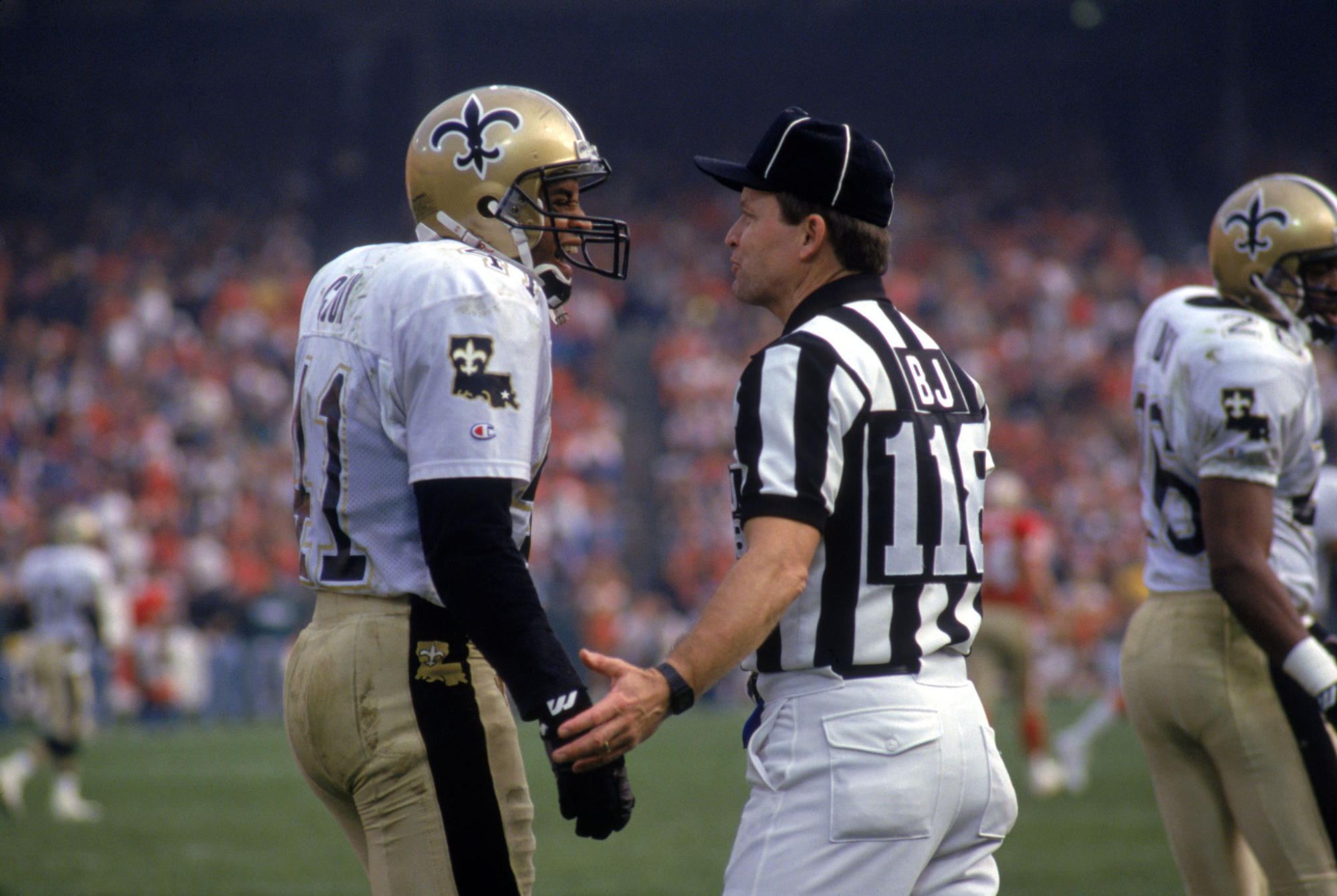

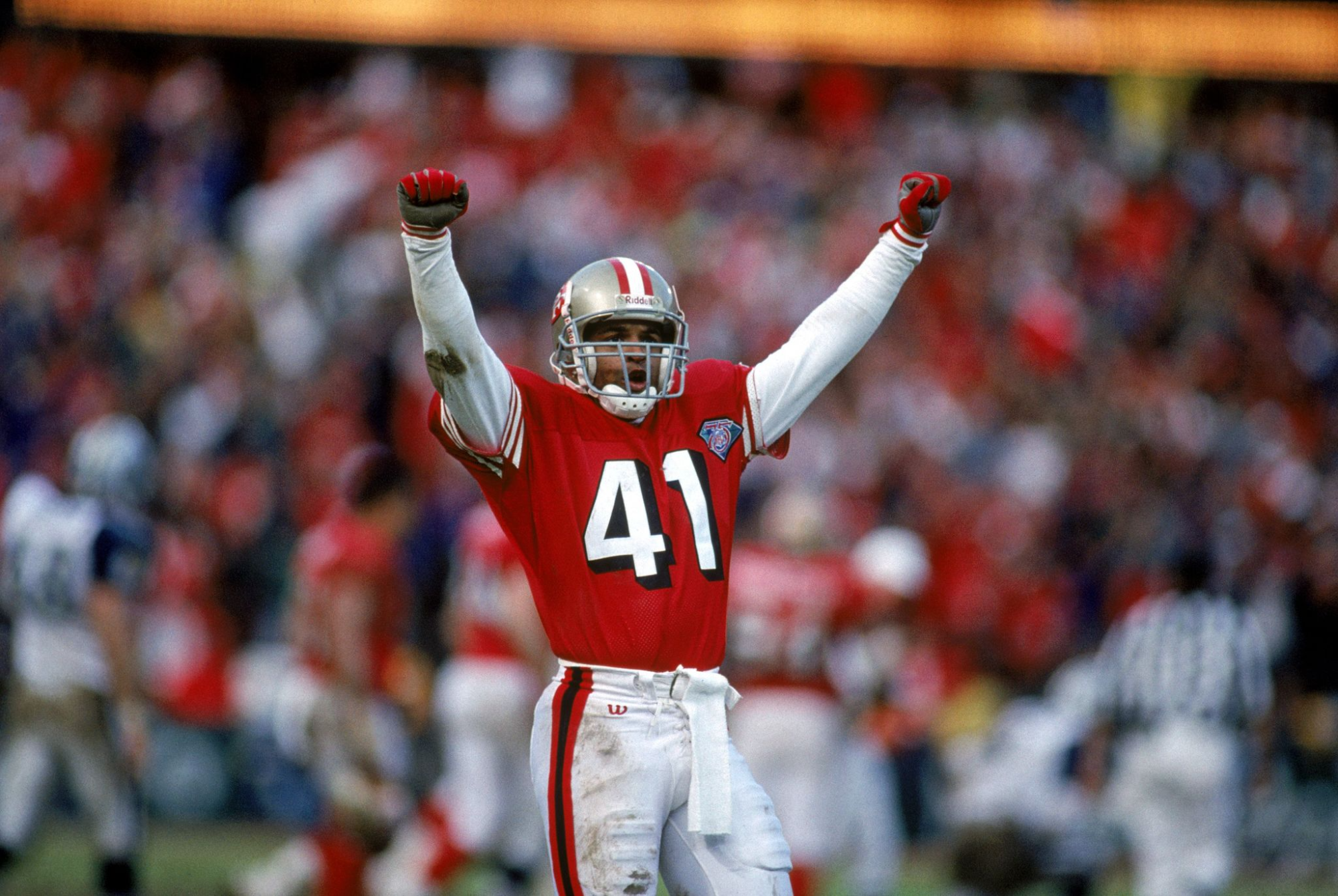

Allow me to introduce myself. My name is Toi Cook, and I spent 11 seasons as a defensive back in the league, my first seven with New Orleans and two each with San Francisco and Carolina. I grew up in Los Angeles, went to school at Montclair Prep in the San Fernando Valley and Stanford, and relied on my intellect to have as long a professional career as I had. You’ve got to be pretty smart to make it that long as an eighth-round draft pick. Obviously, you’ve also got to be the kind of athlete who can compete at a high level.

If you just look at the way we practiced and played, where hitting was a way of life, you have to assume I might have lost some cognitive ability. While mine is still high, and I’m not as bad off as many former players, I still lost something. How much may not be determined until later, as it was with the tumultuous journeys of Junior Seau, Dave Duerson and John Mackey, men who truly gave their lives for the game.

Still, the NFL rejected my claim for a portion of the concussion settlement, despite the diagnosis of an acclaimed neurosurgeon. They didn’t tell me why they rejected me. You’re just supposed to accept it. That’s typical of everything in our society. There’s no transparency.

Things aren’t always as they seem. I learned that as a kid when I saw the magic of TV from a different perspective. My dad was a cameraman at Paramount and worked on shows like “Soul Train” and “Entertainment Tonight” and “What’s Happening!!” I grew up around Hollywood and went to school with Barry White’s daughters, Robert Conrad’s kids, the daughters of Tom Bosley and Peter Ueberroth. As a kid, I went on a date with Rosie Perez.

I mention this because these experiences took something that is so mysterious to so many and demystified it for me. It wasn’t magic anymore. It was studios that were so cold the producers were running around in sweaters when it was 90 degrees outside. It was, “Oh, so that’s how this stuff happens.”

The NFL is pledging to halt the use of ‘race-norming’ in the $1-billion settlement of brain injury claims and to review claims by Black players for any potential race bias.

When I got to college, the NFL was kind of demystified too. When I was a sophomore at Stanford, I got to work out in the summers with NFL players who would come around. Some of the 49ers like Ronnie Lott and Eric Wright, Joe Montana and Mike Wilson. Jim Plunkett would come back to Stanford, and so would Kenny Margerum.

I’m out there covering pros who had been in the league for seven years. I’m all over them. That’s when Ronnie, Eric and Dana McLemore told me, “Toi, you can play in the league, no question.” Once I heard those words, that became my focus.

But once I got to the NFL, I learned pretty quickly that I would be judged on more than my level of play. I was outspoken, and if I had a problem with something, I didn’t hold my tongue. I had conversations with the late Jim Finks, the former Saints general manager whom I still love, and with coach Jim Mora, whom I really love, and those conversations weren’t always pleasant.

I should point out that Jim Mora by no means has ever done anything wrong to me. The only thing he did was help me play 11 years in the league. I wouldn’t have lasted that long without Jim Mora. That being said, I was kind of a problem player to him.

After all, how many DBs have a call-in show after games? I had one in New Orleans. Those are usually reserved for quarterbacks, running backs, guys like that. But I had one. Like I said, I didn’t hold my tongue.

One time, I was part of a group of New Orleans defensive backs holding out for better contracts. So the Saints signed a couple of players from the Canadian Football League and gave them, if I recall, $200,000 bonuses. They weren’t going to give that kind of money to us. I said at the time: “I didn’t know that the CFL was more valuable than the NFL. Maybe I should have gone from Stanford to the CFL first.” That didn’t go over well.

Race-norming assumed Black players started out with lower cognitive function, making it harder for them to qualify for league concussion case payouts.

When I felt like we were mistreated, I said, “This isn’t slavery.” People didn’t forget that. They repeated it back to me a lot during my career. What I meant by that was, “Just because you have my rights as a player doesn’t mean you’re allowed to treat me this way.” God forbid someone say that.

So now the NFL and lead attorney Christopher [Seeger] come out and promise they’re going to eliminate race-based norms, that they’re sorry for the pain this has caused Black former players and their families.

The first thing that comes to mind for me is, somehow Christopher [Seeger] got paid and we didn’t. He didn’t play one down in the NFL, not one practice. He set up a system where he cut out a lot of us, and it’s a terrible system — except for the system for him.

The question now is, how do you move forward? I believe the league should offer a different settlement to the players, call it an offer and a compromise. I think it should be $100,000 for each year that you played in the NFL. It’s a one-time offer and if you agree to that deal, you agree not to sue the NFL for any future dementia or whatever you might suffer.

I would accept that deal ASAP, and I know a lot of people who would accept that deal. And the people who feel like they need more? I can’t fight that fight.

Can the NFL afford it? Yes. The new TV deals will pay more than $300 million per team per year. The league was built on the shoulders of the players who came before this generation. You don’t practice the way we practiced, you can’t line up the same way, you don’t have the same formations in place. Because the NFL protects its players now in a way that it didn’t before. Why does the NFL not practice the way we did anymore? Why did the league legislate out certain hits and officiate plays differently than when I played?

In my opinion, that’s a total admission of fault. Why else would the league change the rules on physicality in practice and games? As proof of the old days, we have those videos like “Crunch Course” that glorify those hits that are now outlawed.

So if you’re now asking us to take another cognitive test, and then just give us some lame excuse about why we don’t qualify ... that’s just not right.

We took a beating. Pay us for it.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.