Tom Henschel woke up in New Orleans on the day of Super Bowl VI gasping for air. Unsure whether he was hung over from a night of Bourbon Street revelry or having an allergic reaction to a bowl of seafood gumbo, he stumbled out of his hotel room and onto the street, where he fell to his hands and knees.

“I couldn’t breathe,” Henschel, now 80, recalled of that scary Jan. 16, 1972, morning. “I thought I was gonna die.”

A police officer noticed Henschel in distress, loaded him into his squad car and rushed him to a hospital. The next thing Henschel remembers is waking up in the emergency room with an IV in his arm and an oxygen mask covering his mouth and nose. A nurse wheeled him to a private room and asked if she could get him anything.

“I said, ‘No, but I’m going to the game today,’ ” said Henschel, a Pittsburgh native and lifelong Steelers fan. “She said, ‘No you’re not. You’re going to have to watch it on TV here.’ As soon as she walked out of the room, I pulled the IV out, ripped off the oxygen mask, got my clothes and ran out of the hospital.”

Henschel took a cab to his hotel and met his girlfriend, who had flown in from Miami that morning. The two had lunch before heading to Tulane Stadium, where the Roger Staubach-led Dallas Cowboys beat the Miami Dolphins, 24-3.

To this day, it’s the closest Henschel has come to missing a Super Bowl.

———

Don Crisman was cutting it close. It was the morning of Super Bowl XXXII in San Diego on Jan. 25, 1998, and the Kennebunk, Maine, resident and lifelong New England Patriots fan had not procured a ticket to the game.

His ticket sources with the Denver Broncos had dried up. The buddy he went to the first 31 Super Bowls with, Stan Whitaker, could score only two seats, for himself and his wife.

Before going to breakfast in his San Diego-area hotel, Crisman pinned a card to his shirt with the message, in black magic marker: “Need one ticket. Have never missed a Super Bowl. Need to keep streak going.”

Crisman, now 85, said the card elicited “a lot of snide remarks” from people questioning its veracity but no ticket. Next stop: downtown to look for a scalper.

NFL roundtable: The Rams need to end a five-game skid against the 49ers to clinch the NFC West, and it’s do or die when the Chargers visit the Raiders.

“I got on the elevator to go to my room, and a fellow says, ‘I have three friends upstairs, but a fourth guy can’t make it,’ ” Crisman said. “They were doctors from North Carolina and Georgia.

“They were willing to sell me a ticket, but they didn’t trust anybody, because they sold tickets in the past that were double-scalped, and they didn’t like that. So they said I had to stay with them for the rest of the day.”

It was about 9 a.m. The game started at 3:30 p.m. Crisman said he’d do it, but for good measure, he retrieved some newspaper articles from his room proving he’d been to every Super Bowl. The doctors accepted his explanation.

“People say I’m making it up,” Crisman said, “but I actually have a letter from one of the doctors confirming what I just told you.”

———

Gregory Eaton, an 82-year-old lobbyist and small-business owner from Lansing, Mich., booked his flight and hotel room for Super Bowl LVI in SoFi Stadium on Feb. 13 in early December.

A longtime Detroit Lions season-ticket holder and one of fellow Lansing native Magic Johnson’s childhood mentors, Eaton is expecting to secure two tickets, at a cost of $2,000-$3,000 per seat, through the NFL.

Eaton got free tickets to the first Super Bowl in the Los Angeles Coliseum on Jan. 16, 1967, through his buddy from Michigan State, Herb Adderley, a Green Bay defensive back who started in the Packers’ 35-10 win over Kansas City that day.

When the Packers reached the second Super Bowl — the first two officially were called AFL-NFL World Championship Games — Eaton traveled to Miami to watch them beat the Oakland Raiders 33-14 in the Orange Bowl.

Eaton has gone to every Super Bowl since, all 55 of them, and he’s not about to miss No. 56, no matter what his doctors say.

“I have prostate cancer — I had it once, and then it came back on me — and they found a spot on my right kidney that’s cancerous,” Eaton said. “They want to go through my stomach and into my kidney to cut it out to save that kidney.

“I told them, ‘Whatever you do, it’s not moving that fast, and I’m not doing it until after the Super Bowl.’ My sister is a doctor, and she looked at me like I’m crazy.”

———

Three octogenarians from three different states with three different rooting interests and one common bond.

Henschel, Crisman and Eaton are the surviving members of the Never Miss a Super Bowl Club, an exclusive group of fans that has attended every game, from a Bart Starr-led Packers win in January 1967 to a Tom Brady-led Tampa Bay win in February 2021, and — despite another COVID-19 surge — plans to be in SoFi Stadium for Super Bowl LVI.

Club members were featured in a VISA commercial in 2010. Several have been on the NFL’s VIP Super Bowl ticket list for decades. They usually gather for a “media day” to share their Super Bowl memorabilia and memories with reporters and fans on the Friday before the game.

“I’ve had so much fun,” Henschel said. “Going to the Super Bowl is like New Year’s Eve and the Fourth of July put together. To be healthy enough to even be able to attend all these games and never miss one … geez, I consider myself one of the luckiest guys in the country.”

The club numbered five through Super Bowl XLII in February 2008. Then Whitaker, a Denver resident who had gone to 42 Super Bowls with Crisman, dropped out because of health reasons in 2009 and died in 2013 at age 91.

Hall of Fame receiver Terrell Owens, 48, said he’s willing and able to replace Antonio Brown for a playoff run with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

Bob Cook, a Brown Deer, Wis., native and a longtime Green Bay season-ticket holder, attended 44 Super Bowls before being hospitalized because of cancer-related complications in February 2011, days before his beloved Packers beat the Steelers 31-25 in Super Bowl XLV. He died a few days later at age 79.

Larry Jacobson, a longtime San Francisco 49ers season-ticket holder who became one of Crisman’s best friends after the two met at Super Bowl XXXIV in January 2000, died in 2017 at age 78.

But the club gained a member at Super Bowl 50 when a Detroit television station featured Eaton in the buildup to the February 2016 game between the Broncos and Carolina Panthers.

“People have a tendency to think we’ve all been together from the beginning,” Crisman said. “But that’s not the way it was.”

———

Crisman, a retired telecommunications equipment salesman, took a three-year job assignment in Denver in the 1960s and befriended several executives — who were big football fans — from a local bank. Soon, his fall weekends were filled with Air Force Academy games on Saturday and Broncos games on Sunday.

The bank had sponsorship deals with the Broncos and was given five tickets to the first Super Bowl. Crisman and his friends jumped at the offer and traveled to Los Angeles, where the Packers beat the Chiefs in a half-empty Coliseum.

“Tickets were $12 for the best seats, and they had $10 seats and $6 seats in the end zone,” Crisman said. “That’s what started it all.”

Crisman barely made it to Super Bowl II. He had moved back to Maine and arranged a business trip to Atlanta the week before the game, thinking it would be any easy jump from there to Miami.

A sales agent who owned a plane offered to fly Crisman to Miami that Saturday morning, but an ice storm forced them to land at an abandoned Air Force Base in Orangeburg, S.C.

They hopped a fence, hitched a ride with a police officer to a rental-car agency, drove about 40 miles to Columbia, S.C., and took a train from there to Miami, which took more than 24 hours.

“There were so many damn stops, I thought I’d never get there,” Crisman said. “When I did, I had 2 ½ hours to meet the guys before the game.”

Three of his five buddies dropped out before Super Bowl III, but Crisman and Whitaker kept going, bringing their wives and kids and turning Super Bowl trips into family vacations.

“Stanley started referring to us as the Never Miss a Super Bowl Club,” Crisman said. “We thought we were the only two members.”

Crisman and Whitaker were in line for a taping of “The Tonight Show” a few days before Super Bowl XVII in the Rose Bowl in January 1983, when a man behind them overhead them talking about attending every Super Bowl.

And two became three.

———

From the time he was 5 years old, Henschel remembers his father bundling him up and taking him to Friday night high school games in the Pittsburgh area. As he got older, they attended Pitt games on Saturday and Steelers games on Sunday.

“I was too small to play football in high school,” the 139-pound Henschel says, “but I became a huge football fan.”

Henschel moved to Chicago in 1965 to work as a gate agent for Northwest Airlines. He took a part-time bartending job at an O’Hare Airport-area pub called “Some Other Place,” where Chicago Bears players often gathered.

Henschel befriended some players, who gave him tickets to four of the first five Super Bowls. He went to Super Bowl III without a ticket determined to see Beaver Falls, Pa., legend Joe Namath quarterback the New York Jets against the Baltimore Colts, “but I picked one up from a scalper for $12 four hours before game time,” he said.

After surviving his shellfish-inflicted wound in New Orleans, Henschel began saving money all year for tickets and flying to the Super Bowl city — usually for free as an airlines employee — the Friday before the game. Tickets for the first dozen games were relatively cheap and easy to find.

Rams Jalen Ramsey and Taylor Rapp did have an argument on the field against Baltimore last week, but they’ve mended fences and moved on to 49ers game.

“I’d wave a few hundred-dollar bills around,” Henschel said, “and get a ticket.”

Henschel got married “between Super Bowl XII and XIII,” he said — that’s 1978 for you and me — and when his wife, Regina, discovered Henschel had been scalping tickets, she took a picture of Henschel holding a framed collage of his first 12 Super Bowl tickets and sent it to the NFL, along with a poem:

Tom Henschel is my name

Football is my game

Twelve is in my frame

Thirteen is my aim

“Sure enough, a few weeks later, we get an invoice from the NFL for four Super Bowl tickets,” Henschel said. “Someone took a liking to my wife’s little poem.”

Henschel continued purchasing tickets through the NFL, taking his father, wife, brothers, sisters, nieces and nephews to games. In line to see Johnny Carson in 1983, he overheard Crisman and Whitaker talking about their streak.

“I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me — I’ve been to every game — I thought I was the only one,’ ” Henschel said. “We exchanged phone numbers, and the three of us hooked up every year during the Super Bowl.”

When Henschel walked out of that hospital room in New Orleans 50 years ago, he wasn’t so much motivated to keep a streak alive.

“I didn’t know if I’d ever see another Super Bowl,” he said. “The most important thing was meeting my girlfriend, getting to my hotel before she did.”

But as his collection of ticket stubs and game programs grew, a passion became an obsession. He estimates he’s spent at least $150,000 on Super Bowl expenses.

“I was so much into football growing up, I thought it would be fun if I could just keep going to the Super Bowl,” said Henschel, who has a winter home in Tampa, Fla. “Once I got to 20, I said I’ve got to at least get to 30. Thirty was no problem because I was still young and restless, so I knew I could make it to 40.

“When I got to 40, my goal was to get to 50. But now? Gee whiz, I really want to make it to 60. I think if I make 60, they could probably put me away.”

———

Eaton went to that first Super Bowl in Los Angeles by himself. He traveled to Super Bowl II in Miami with four businessmen from Lansing, but the hotel his colleagues booked did not accept Black people.

Eaton roomed at the Hampton House Motel in Liberty City, where Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay) stayed after beating Sonny Liston for the heavyweight title in 1964, and where athletes such as Jackie Robinson and Joe Louis and musicians such as Sammy Davis Jr., Sam Cooke and Nat King Cole stayed in Miami.

Chargers edge rusher Joey Bosa and Raiders quarterback Derek Carr exchanged barbs after L.A.’s 28-14 victory in October, but with showdown ahead they stick to compliments.

“It’s crazy to even think that now,” Eaton said of the segregation that still existed in the South. “You have to realize that in the 1960s, even pro ballplayers couldn’t stay in certain places. They had rooming houses to stay in.”

Eaton’s experience at Super Bowl II in Miami made Super Bowl XXII and Super Bowl XLI extra special.

Doug Williams became the first Black quarterback to win the Super Bowl when he threw for 340 yards and four touchdowns in Washington’s 42-10 win over Denver in San Diego on Jan. 31, 1988.

“When I was coming up, Blacks couldn’t play quarterback — they said we weren’t smart enough,” Eaton said. “I’m not trying to bring race into it, but being 82 years old, I’ve seen it all. I’ve been through it all.

“So when people who look like me do something that’s great and good, we’re proud of it, because they proved we can do it. And it helps the next generation and generations after that.”

Nineteen years later, in the first-ever Super Bowl matchup between Black coaches, Tony Dungy’s Indianapolis Colts’ beat Lovie Smith’s Bears 29-17 in Miami on Feb. 4, 2007.

“They asked me what team I was cheering for,” Eaton said with a hearty laugh, and I said, ‘I can’t lose, brother!’ ”

Eaton loved football and could afford to travel to the Super Bowl, so he was able to keep the streak going through business associates, family members and friends. He even shelled out $30,000 for tickets in his suite for Super Bowl XL in Detroit’s Ford Field in February 2006.

“I had my own group of guys I’d go with from all over the country,” Eaton said. “A lot of them died off. A lot of them didn’t go to all of the games, like myself. The only thing I missed was the commercials. I had my son tape the games for me so I could watch them.”

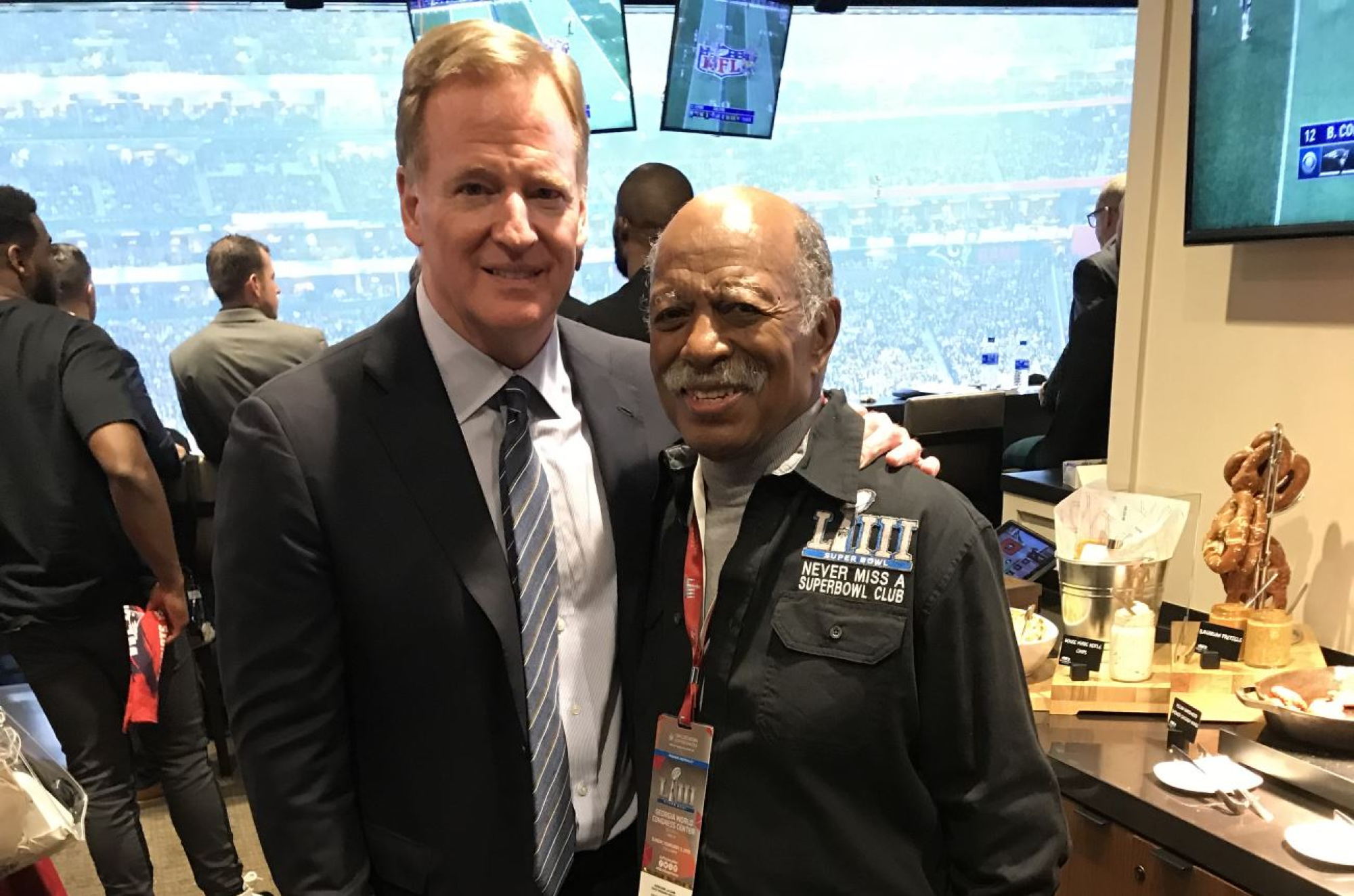

Eaton, who was invited to Commissioner Roger Goodell’s suite during the Super Bowl in Atlanta three years ago, never came as close to missing a game as Crisman and Henschel.

But there was some concern last winter when the trio was told in early January that the NFL would be unable to fill their ticket requests for the game in Tampa, where a pandemic-reduced crowd of 24,835 included 7,500 first-responders and healthcare workers.

“I was worried the streak would end,” Eaton said. “Then I got the call from the NFL on Jan. 17, my birthday. They said, ‘Mr. Eaton, can we have your credit-card number?’ The tickets came in the mail. They were $3,000 each. It’s amazing how expensive it’s gotten.”

Two other games stand out in Eaton’s mind — Super Bowl LI, when the Patriots overcame a 25-point third-quarter deficit in a 34-28 win over Atlanta — “Probably the greatest game ever,” he said — and Super Bowl XLIX, when Seattle, on the New England one-yard line and driving for a winning score, opted to pass instead of run.

Malcolm Butler’s interception in the final moments sealed the Patriots’ 28-24 win.

“That was terrible — I felt sorry for that whole team,” Eaton said of the Seahawks. “They had the Super Bowl won.”

Henschel, of course, loved all six Steelers wins, but especially Super Bowl XIV, when Pittsburgh beat the Rams 31-19 in a thriller that was played before a record crowd of 103,985 in the Rose Bowl.

Crisman is partial to the Patriots’ six wins, especially the Brady-led comeback against the Falcons and Super Bowl XXXVI, when Adam Vinatieri kicked a 48-yard field goal as time expired to give New England a 20-17 win over the St. Louis Rams and its first Super Bowl title.

Another of Crisman’s favorites: Super Bowl III, when Namath led the Jets, of the supposedly inferior AFL, to a 16-7 win over the heavily favored Colts of the NFL.

“Nobody thought that could ever happen,” Crisman said. “There were sportswriters who said the AFL wouldn’t win in the first 10 years. Joe proved them wrong, and then Len Dawson proved them wrong (in Super Bowl IV, leading Kansas City to a 23-7 win over Minnesota). I think they legitimized the game. I think the game could have been a failure if the NFL dominated over the old AFL.”

———

As much fun as they’ve had, memorabilia they’ve collected and friends and memories they’ve made along the way, Crisman, Henschel and Eaton know their streaks will end.

Father Time, as they say, is undefeated. So is Grandfather Time.

Henschel has not had any major health issues and is in good enough shape to golf twice a week. He’s optimistic about reaching 60 Super Bowls.

Eaton will need surgery to remove the tumor on his kidney, but otherwise, “My heart is strong, and I have a will to live,” he said. He’ll need that and more if he’s ever to see his Lions reach a Super Bowl.

But Crisman, whose daughter, Susan, has been traveling with him to games, said Super Bowl LVI might be his last. He’s being treated for ulcerative colitis and has other health issues. He’s slowing down.

“Getting old isn’t pretty,” Crisman said. “I’m going to go as long as I feel healthy enough, and not in my wildest dreams did I think we’d get this far. But I’m nearing the end. This could be the final one. Who knows? It’s up to the Big Guy Upstairs.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.