There are very few activities and events in our global society that transcend the amalgam of socioeconomic, religious and cultural differences quite like basketball. The game’s inviting, multicultural nature has made it one of the most entertaining, inclusive sports around the world. It is a meritocracy, a connector. It doesn’t matter your culture, gender or measurements; if you can “hoop” and be an asset to a team, organized or not, you will be welcomed and accepted.

I think back to 2016 when 15 of the first 30 NBA draft picks were international players. Europe boasted nine of those 15 picks. Europe has long been viewed as the second-best basketball market for basketball talent outside of America by casual fans. However, some basketball purists — and I count myself among them — hold European basketball as the best brand of basketball development in the world. I have a unique perspective regarding international basketball in Europe, having played eight of the 10 years of my professional basketball career in Europe (England, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Portugal, Czech Republic, and Spain).

For most aspiring basketball players, the NBA is the ultimate goal. However, for the tens of thousands who don’t make the League, “overseas” becomes their target. There are numerous professional basketball markets around the world with the opportunity to become a pro, see the world and provide for your family while doing what you love.

While playing professional basketball abroad can be a life-changing, fulfilling, even lucrative experience, American basketball players are not immune to the trials and tribulations of local citizens in the country in which they play. I learned this firsthand in 2013 while playing for Ilisiakos B.C. in Athens, Greece. Although I played in the top league in one of the most respected basketball markets in the world, Greece was going through its most catastrophic economic downturn since the Second World War, and my team was not immune to it. There were protests every day, our sponsors were no longer able to fulfill their obligations, salaries were late or not paid, and my Greek teammates went on strike by not participating in practices until they received their salaries. To date I still haven’t received my full salary.

::

That brings me to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a far more serious crisis than even economic depression. Ukraine is a robust basketball market for American players, men and women. My client Adrienne Godbold, a former Big Ten sixth player of the year at Illinois, signed with Dynamo Kyviv Basket in Ukraine’s capital, now the flashpoint for the Russian invasion. Europe is the biggest professional basketball market for women, and those jobs are at a premium.

On Jan. 3 Godbold sent a text to me saying that she had been hearing rumors of Americans evacuating the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv and asked, “Should I be worried?” I asked if she felt safe, and she responded, “I don’t feel in danger or anything.” Dynamo Kyiv assured us that “Russia has been threatening Ukraine for eight years and there’s nothing to worry about. The league will continue.”

On Jan. 26, Godbold and the other Americans in the Ukraine received emails from the U.S. Embassy stating that the situation had become more dire and that they should evacuate the country immediately. We began devising a plan, based on her contract, to get her evacuated while receiving her FIBA release so she could sign with another team in Europe. The team, however, could withhold her rights preventing her from signing with another team because Russia had not officially invaded Ukraine, which would have allowed Godblod to invoke the force majeure clause in her contract.

Ukrainian tennis player Yuliia Zhytelna has found support from Russian Cal State Northridge doubles partner Ekaterina Repina during a very stressful time.

Godbold texted me Jan. 30, “I’m scared and it’s starting to weigh on me. I’m laying in bed last night listening to seven big booms wondering if they’re bombs in the distance. I can’t do this. It’s not worth it. And I’ve heard Russia plans to invade next month.”

On Feb. 4 we officially asked the Ukraine team for Godbold’s release, citing the pending war. Her coach, however, insisted that she should feel safe. “There are no soldiers with guns or anyone scared here so you will be fine,” he told Godbold. “The basketball federation didn’t cancel the season. We are safe here in Kyiv so I don’t know why you are scared or unsafe.”

“It doesn’t matter what I see,” Godbold responded. “I don’t feel safe and it’s stressful for me and my family.”

That prompted this unconscionable comment from the coach, who in reference to Godbold’s native city, said, “I know there is violence in Chicago, but you feel safer there than here right now.” Sentiments like these are not uncommon by overseas clubs.

Godbold texted me on Feb. 6, “Mike, I don’t feel safe. None of the news has changed in the last two weeks. It’s only gotten more scary, not just for me, but for my family as well. … I’m thankful the team wants me to stay, but at this point it’s getting to me. I just got my COVID test and will be leaving in the next 24 hours.”

I advised Godbold to wait another day before leaving so we could exercise her buyout clause since a team in Finland was interested in signing her for the remainder of the season. Godbold, however, was adamant about leaving that day.

Typically when an American is signed to an international professional basketball team, the team buys a round-trip ticket in the player’s name. Godbold changed her round-trip ticket on Feb. 7 to return to Chicago. When the team became aware of Godbold’s decision to leave, they notified us that they viewed her departure as akin to going AWOL. The team maintained their stance that the country was safe, and demanded that we pay restitution although Godbold had fulfilled the terms of her contract up to that point. She has returned safely to Chicago. However, Dynamo Kyviv Basket still has not released her from her contract, which caused her to lose the deal with the Finnish team.

::

For all the headaches that came with her decision, Godbold was fortunate to have left Kyiv before the Russian invasion. There remain a number of American basketball players who found it much more perilous to evacuate. One of these players is Maurice Creek, who was a standout basketball player at Indiana University and George Washington. Since graduating from George Washington, Creek has been playing professionally in Europe. He signed to play for MBC Mykolaiv Ukraine for the 2021-2022 season and was forced to decamp to a bomb shelter there. We have kept in contact via voice message. On Feb. 25, I messaged Creek to check on his well-being.

The uncertainty and fragility of the current events initially left Creek unable to travel to any neighboring country. The airport in Kyiv is no longer operational, and the roads in all directions to neighboring borders, specifically toward Poland and Romania, were completely gridlocked.

You might ask why Creek hadn’t evacuated the country earlier as Godbold had? For the very same reasons Godbold’s coaches had given her. “My team was telling me they didn’t think the invasion would happen,” Creek said. “I was trying to leave, but they were telling me to wait, and when they realized it happened I was stuck here.”

The conditions of the bomb shelter, Creek wrote, were “very cold!! People are just laying down. I have a bag of snacks with me. I’m just trying to stay safe. I don’t know how long I’ve been in here, maybe about an hour. I’m scared bro. … I’m not going to play around with it, I’m terrified!! I’ve never been in a bomb shelter a day in my life. There are no bathrooms, people don’t have masks on, but nobody is worried about COVID, we’re all just worried about the bombs.”

Creek said the team had been communicating with him and his teammates about how they might evacuate with the Russian invasion closing in on its first week. The vice president and coaching staff were still in Mykolaiv assisting “all of his American and Ukrainian teammates” in their evacuation efforts, Creek told me. The vice president of his team had secured transportation for Creek, but a safe route out of the country was taking days to be established.

Despite the immense ordeal Creek endured, being an American professional basketball player has been an advantage. In addition to the transportation resources at his disposal, he was being treated with kindness.

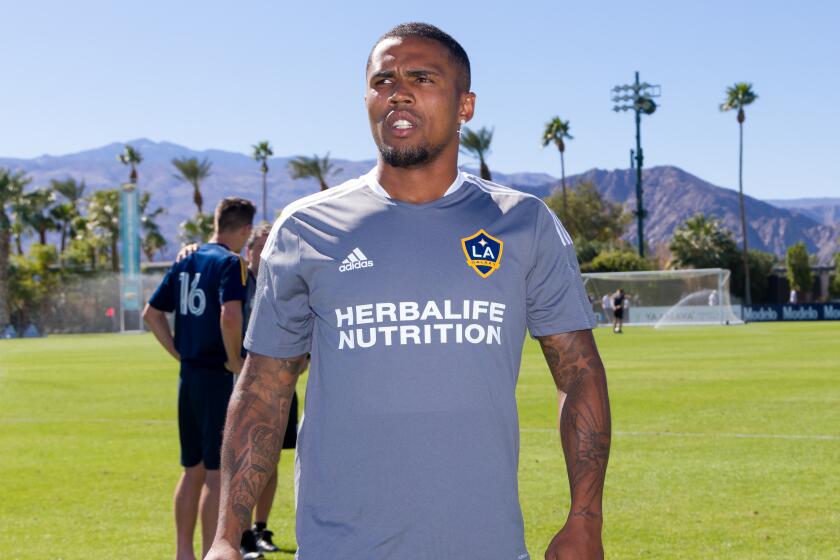

Galaxy acquisition Douglas Costa became a star with Shakhtar Donetsk in Ukraine. Now he watches developments in his former home from afar with fear.

“We are all one big family down here,” he wrote. “Everyone is just making sure everyone is staying safe, helping each other with food, and hopefully we don’t have to stay down here too much longer.” (For all kindness the locals in Mykolaiv had extended Creek, I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the growing reports of discrimination towards some foreigners, specifically Africans in their efforts to evacuate Ukraine.)

Finally, there was good news, a breakthrough. Early Monday morning, Pacific time, I heard back from Creek. “I’m in the car fam,” he texted. “I’m getting out. I’m so happy fam.”

He said he would text me once he reached the other side of the Moldova-Ukraine border. Late that afternoon, there was a ping. He had crossed the border and would soon be flying to Romania.

Michael Creppy Jr. is the founder and president of Vindicated Sports, an international basketball consulting company. A former UC Riverside basketball player, he spent eight seasons playing professionally in Europe.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.