- Share via

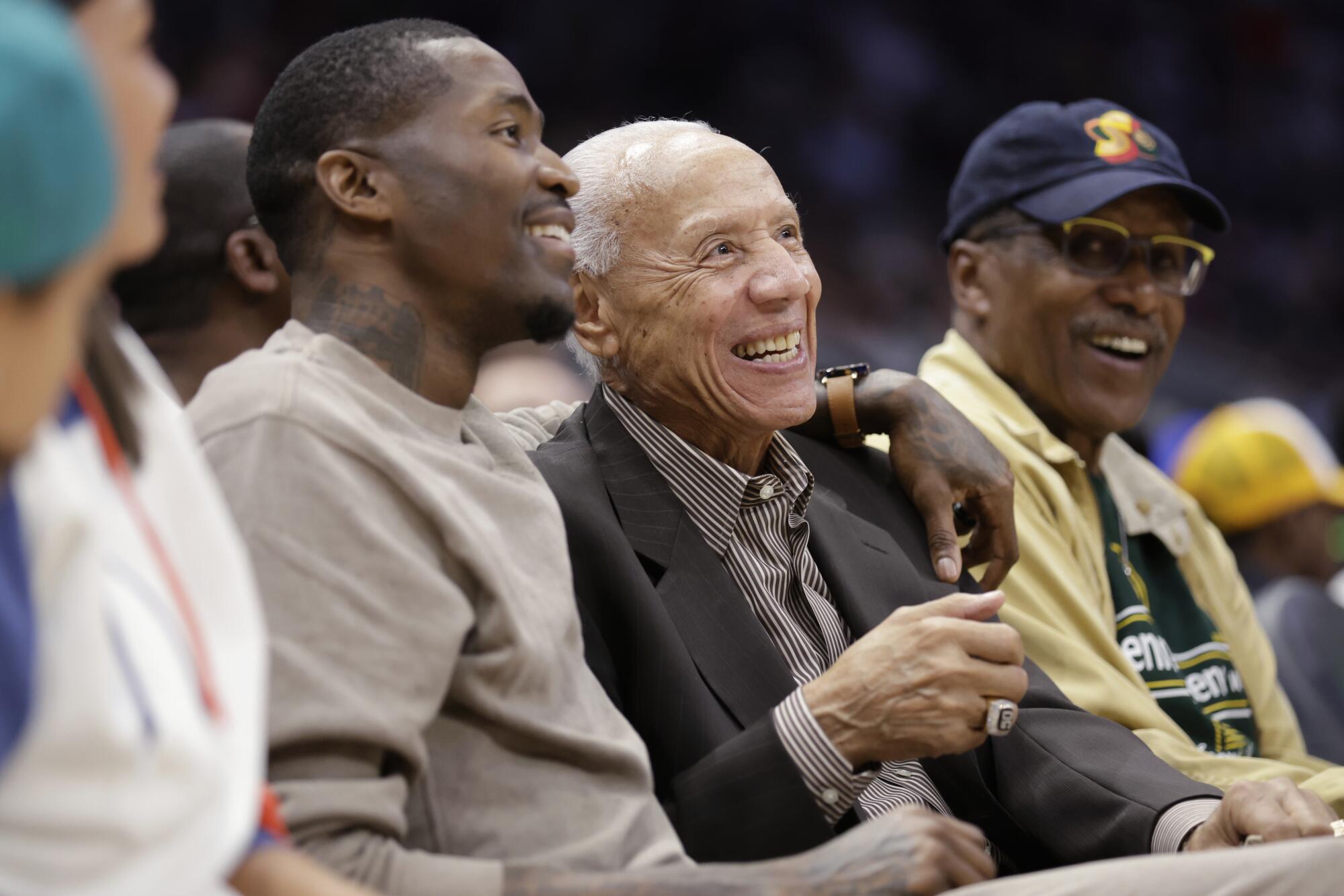

SEATTLE — Washington Gov. Jay Inslee presided over a meeting of Clippers and Portland Trail Blazers captains at midcourt before tipoff Monday evening as Lenny Wilkens, the coach of Seattle’s lone NBA championship team in 1979, found his courtside seat. On the outer edge of the temporary court inside this city’s two-year-old Climate Pledge Arena roamed Shawn Kemp, Gary Payton and Detlef Schrempf, headliners of the SuperSonics’ 1996 run to the NBA Finals.

Macklemore, the rapper who grew up in Seattle, entered by the Payton-and-Kemp combination and grabbed a microphone. His volume raising, he called the night a reminder that Seattle, which lost the SuperSonics to relocation to Oklahoma City in 2008, deserved another NBA team. The declaration earned cheers, but he turned out to be the opening act.

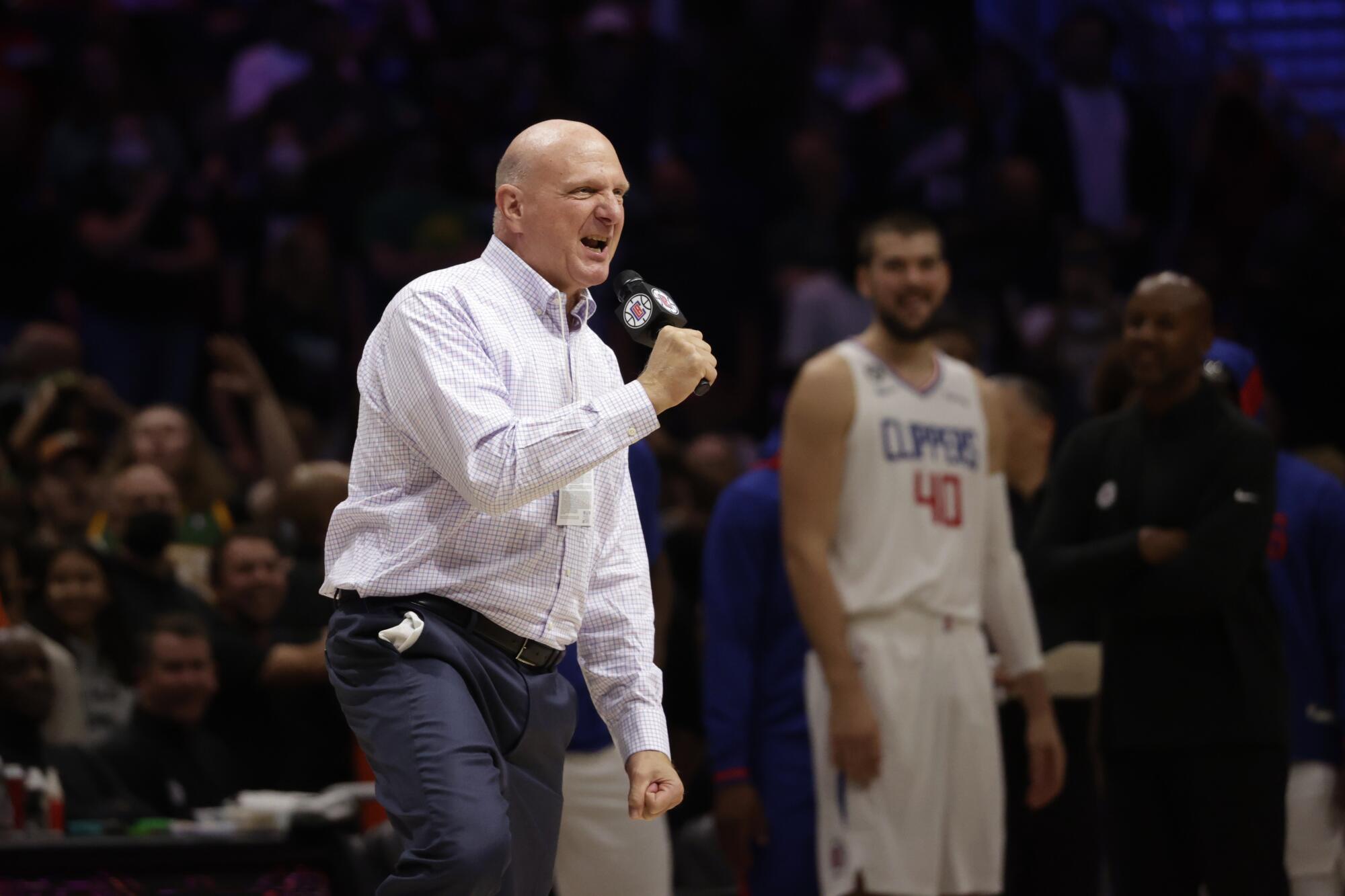

Steve Ballmer, the Clippers owner once famous for his rabid speeches in front of software developers, took the microphone next. Within 90 seconds, he was rocking back and forth while bellowing, a sold-out crowd rising from their seats.

“If this is a basketball city, damn it, let’s hear it!” Ballmer said.

In a sport in which preseason basketball games can play out like lifeless affairs, less enjoyed than endured, Monday night here felt different, a big-tent revival stopping for the evening to welcome a city full of fervent basketball believers. Seattle has long been a basketball city, but for the first time in four years, since the last exhibition between NBA teams was played here, and only the second time since the Sonics’ departure, this was again an NBA city for one night — the crowd still in their seats long after both teams’ best players had gone to the bench for rest, chants of “SuperSonics” ringing through the arena in the final minutes of the Clippers’ victory.

Now the multibillion-dollar question is how long it will take for the NBA to return permanently, if it does at all. There is cautious optimism that league expansion will be this city’s answered prayer 14 years after an impasse over a new arena led to the team’s departure.

“It was part of our childhood, that was our team, and it’s one of those things you don’t know what you have till it’s gone and it kind of got swept out from underneath us,” Macklemore said. “Here we are, how many years later? Fourteen years later and we’re still waiting.”

The wait won’t end immediately. NBA Commissioner Adam Silver called Seattle and Las Vegas “wonderful markets” but denied rumors in June that the league will add a team in each market in 2024, saying that “at some point this league invariably will expand, but it’s not at this moment that we are discussing it.”

That hasn’t kept the discussion growing or the speculation mounting among fans who remember the Sonics’ 41-year history, support the WNBA’s Storm in droves and flock to the free summertime pro-am event hosted at Seattle Pacific University by Jamal Crawford, the guard who played parts of 20 NBA seasons.

“We’re not trying to get ahead of the league whatsoever,” Crawford said, “but the passion still burns and it will always still burn.”

Tim Leiweke, the chief executive of Oak View Group, which developed Climate Pledge Arena on the site of the former Key Arena, designed the arena to draw not only the NHL’s Kraken, who debuted last season, but also meet NBA specifications and called Monday’s exhibition a “moment of truth” to show how the arena would hold up to NBA scrutiny.

With the arena in place, what more does Seattle need to do for a team?

“That’s really up to Adam” and the NBA’s Board of Governors “and we’re extremely respectful of, one, if they want to put a team in Seattle,” Leiweke said. “I think some of the mistakes made in the past is they got a little rambunctious with their attempts to have an impact on the Sacramento marketplace, and I was on the board of the directors back then. You don’t want to do that. You don’t want to get ahead of the league, you don’t want to force a decision.

“You don’t want to think at the end of the day that you have leverage or you have the ability to force an issue like this. You don’t. This is really first and foremost if and when Adam and the board of governors want to even consider it.”

As a kid, Crawford had a job hauling food from Key Arena’s basement to its concession stands. The job should have taken him 10 minutes, but he could stretch it to a half-hour, often dawdling by the court, watching the basketball stars he saw on TV.

It is slightly unbelievable, he said, to know that there are teenagers in Seattle raised without having the same chance.

“People watching the game from a distance will see how this city misses their Sonics,” Crawford said.

Mike McGinn understands the difficulty of the wait more acutely than most. Once a New York Knicks fan who grew up imitating the moves of Earl Monroe, he fell for the Sonics so hard after moving for law school that he recorded every game on videotape. He played in Crawford’s pro-am in 2011 and 2013, and on a recent afternoon he mused about longtime Sonics guard Nate McMillan’s plus-minus.

He entered office as Seattle’s mayor in 2010, two years after the team’s sale to a consortium of Oklahoma City businessmen led to its relocation, and McGinn quickly realized his term would be intertwined with the Sonics’ future. At community events with youth, he recalled that “invariably the first question was, ‘Mayor, are we going to get the Sonics back?’ ”

He empathized with the cause but knew the political difficulty with local voters and power brokers. An initiative approved by Seattle voters restricted professional sports teams from receiving city tax dollars unless the investment was returned at least at the rate of a 30-year U.S. Treasury bond. And during a visit to the NBA headquarters in 2012, McGinn came away from a meeting with then-commissioner David Stern believing league officials were still smarting from being rebuffed in their attempts to lobby for a new arena.

“[Stern’s] first question was, ‘Is the [Washington] Speaker of the House the same guy?’ ” McGinn said. “The story was that David Stern wasn’t happy about how he was treated by the Speaker of the House, and those were almost his first words to me.

“It felt to me that the NBA had decided to make an example of Seattle. You didn’t pay for a new arena, your team moved, and that’s how it goes.’”

McGinn was in Dallas in May 2013 attending the NBA’s Board of Governors meeting when it rejected Seattle investor Chris Hansen’s deal to purchase and relocate the Sacramento Kings. Also there, waiting in a side room for the NBA’s decision, was another key player in Hansen’s investment group: Ballmer.

Ballmer left that group in 2014 to explore purchasing the Milwaukee Bucks on his own. He said in a 2017 podcast appearance that he visited the city, drove around its suburbs and went to a game but said the Bucks’ owner had no interest in selling to him, sensing a leeriness because of his Seattle connection.

When Ballmer purchased the Clippers in 2014, that same Seattle connection fueled immediate speculation that the Clippers might one day be on the move for the third time in franchise history. Ballmer still lives near Seattle. He’s a “206 [area code] guy,” said Jason Reid, the director of “Sonicsgate,” the 2009 documentary tracing the franchise’s departure. Reid preferred to avoid doing to another city what was done to Seattle — though he would take the Thunder back from Oklahoma City “in a heartbeat,” he said — but allowed himself to believe Ballmer might move the Clippers.

Yet from the start of his Clippers ownership, Ballmer, who declined an interview request, was publicly steadfast in his commitment to anchoring the Clippers in the country’s second-largest market, with its sprawling potential for ticket-buyers and sponsor dollars. McGinn never heard any dialogue to suggest it was ever Ballmer’s interest, and Crawford, who has known Ballmer for years and played for the Clippers under Ballmer’s ownership, also never believed a move was ever a consideration.

That speculation was officially rendered moot once shovels were put in the ground in 2021 on Ballmer’s privately funded, $2-billion Intuit Dome arena in Inglewood.

“I want to say this unequivocally: Steve is building one of the greatest arenas ever built in the history of live entertainment in Los Angeles,” said Leiweke, who helped develop L.A. Live and Staples Center while running AEG.

“He’s not just 100 percent committed to L.A,” Leiweke added, “he’s 2 billion percent committed to L.A.”

Adam Brown, the writer and producer of “Sonicsgate,” still views Ballmer’s NBA ownership as indirectly positive for Seattle.

“There are only a handful of owners who can go in that room and advocate for the league’s policy,” he said. “I think having Steve Ballmer in there is good for Seattle in all of these talks.”

As Ballmer’s basketball business dealings grew entrenched in Southern California, Leiweke was leaving a job overseeing the Toronto Raptors and Maple Leafs in 2015 to co-found Oak View Group, his new arena construction and management business, when he visited the then-recently retired Stern.

Stern was a mentor, and Leiweke wanted help knowing “where are the emerging markets, and where do I make my bet?” All signs pointed to Seattle. He knew the market well from his brother, Tod, a longtime Seahawks executive who now helps run the Kraken. He understood that even before considering the city’s decades supporting the Sonics and the talent that has flowed from its high schools to the NBA, it is the country’s 12th-largest market, a hub for travelers from Asia and has business wealth fueled by tech giants Amazon and Microsoft.

The city has clearly never lacked basketball boosters. It lost the Sonics because it lacked a building deemed adequate for the NBA.

Earlier attempts by Hansen to develop an arena on land he owns south of downtown never crossed the finish line with the City Council. Oak View Group — which is also currently planning to develop an NBA-ready arena in Las Vegas — made a bid, later approved by the city, to use private funding to rebuild the existing but outdated Key Arena.

The construction process lifted the arena’s historic roof built for the 1962 World’s Fair, dug out everything beneath it and built a new arena capable of holding more than 17,000 for hockey and 18,000 for basketball and then, $1.2 billion later, lowered the roof back down. Fans walk in from the street onto the top floor, with natural light streaming through windows on the upper deck. Oak View Group has a 39-year arena lease with the city, which owns the arena’s land, and a pair of eight-year options that could take the agreement to 55 years.

Design choices unique to basketball are everywhere. A pair of triangular-shaped scoreboards hang over where a basketball stanchion stands. The retractable lower-bowl seating tilts to a higher angle and configuration to accommodate basketball or is lowered for hockey. In addition to locker rooms for the NHL’s Kraken and WNBA’s Storm, about 30,000 square feet of space was set aside for locker rooms for home and visiting NBA teams, plus referees.

The NBA’s collective bargaining agreement with the players union runs through the 2023-24 season, and its television contract expires one season later, with its next broadcast deal expected to inject billions more into the league’s bottom line. A decade ago, Seattle fans saw relocation as their best option to replace the Sonics. Now, expansion — which would trigger fees some estimate in the billions to existing teams — “is really the only hope, and that’s what everybody’s kind of watching,” McGinn said. “Having the arena done I think also feeds that hope, that sustains hope.”

“It does get exhausting to sort of ride the rumor mill and say, when is it our turn?” said Brown, the filmmaker. “But at the same time, the economics are finally solved with the arena. It’s up to the billionaires now to get that deal done.”

If the NBA’s Board of Governors reconsider Seattle, Leiweke said, he believes they will see an arena that has sold out its sponsorship, club-level seating and suites for the Kraken, and has deep-pocketed options for a local ownership group. David Bonderman, a University of Washington alumnus and Kraken majority owner, also holds a minority ownership stake in the Boston Celtics. Leiweke shares enthusiasm freely but speaks cautiously of not overstepping the NBA’s decision-making process.

“There are no side agreements, wink-winks or back-door conversations going on here,” Leiweke said. “Now, do we feel also good about the arena? Yes. Do we think it was designed and built for basketball? Yes. Do we think the economics are such that an NBA team is going to make far more money in our building than trying to build another $2-billion arena? Yes.”

Monday‘s game represented a chance to put all that arena design and planning into action against the backdrop of raucous support, “to show the NBA a little something about how much we really do want NBA basketball back,” Reid said.

The city’s former baseball, football and basketball stars from the city lined courtside seats. Former Sonics coach George Karl earned a rapturous applause. Leiweke hugged Macklemore, who has become entwined with the local sports scene through minority ownership stakes in the Sounders and Kraken and his own golf brand, Bogey Boys. Payton embraced Clippers coach Tyronn Lue, who said the city deserves a team, before tipoff. The seats were full to the top.

“When a crowd comes out like that for a game where neither team is a Seattle team and brings that type of energy, you can’t help but think they need a team here,” Portland star guard Damian Lillard said. “They definitely need a team here.”

McGinn cautioned against the thinking that a new team is inevitable. Yet on a recent weekend downtown and in the Queen Anne, Fremont and University District neighborhoods, Sonics gear was as prevalent as that of the city’s current professional teams.

Said Schrempf, a Sonic for six seasons until 1999 who wore a Sonics sweatshirt to Monday’s game: “I don’t feel like we have to prove that his market is good. I think everyone knows that.”

It was Schrempf who gave voice to the fan base’s conspicuous optimism in a video produced by the Kraken and posted to social media Sept. 26.

Ostensibly, the video teased the unveiling of the Kraken’s new mascot. It also teased the hope of so many NBA believers who have kept the faith for 14 long winters.

In one scene, Schrempf stands in front of three children who were not yet born when the Sonics last played and describes the team’s former mascot.

“But the Sonics will come back to Seattle one day?” a girl asks.

“You’re right,” Schrempf responds. “The Sonics will be back.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.