Appreciation: Unassuming Notre Dame legend Johnny Lujack learned he won the Heisman in the Coliseum

- Share via

It was 1947, and it was not much more than 30 minutes after Notre Dame beat USC 38-7 in the Coliseum before a typical ND-USC crowd of 104,593. Notre Dame entered the game unbeaten and No. 1 in the country. USC entered No. 3.

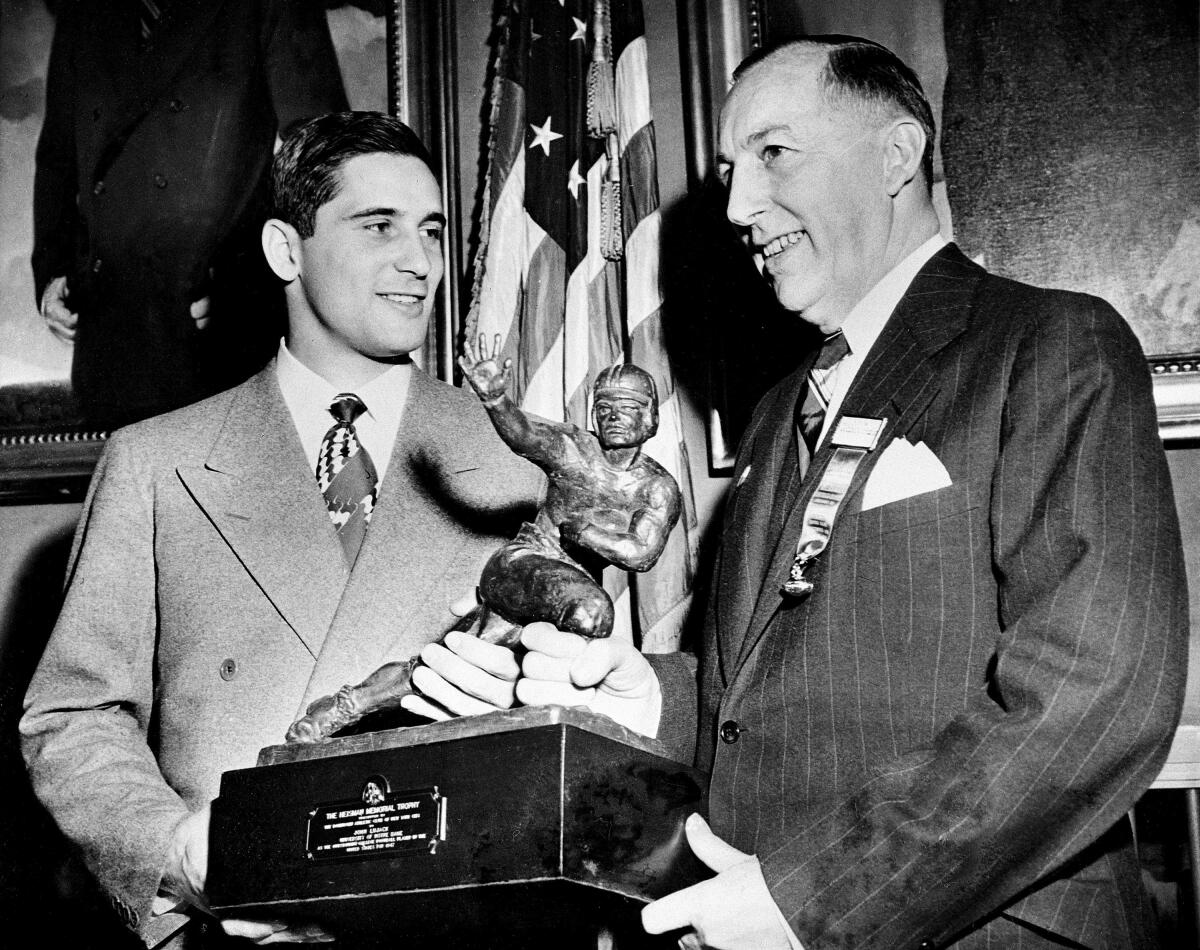

Notre Dame’s quarterback, Johnny Lujack, the kid from Connellsville, Pa., was drying off after his shower when an official-looking person approached. He told Lujack he had won the Heisman Trophy.

That was how it was done in those days. No prime-time TV show. No weekends of fancy meals, big-city hotel rooms and adoring fans everywhere. No agents hanging around to make sure your NIL money gets adjusted upward. They just came and told you. And, as John Heisler, former Notre Dame athletic department official, tells the story, Lujack’s reaction was typical Johnny Lujack, the small-town kid who made good and never quit embraced what he had done or what it meant.

The conversation went like this:

Official: “You have won the Heisman. You will need to go to New York City.”

Lujack: “How do you get to New York City?”

Official: “You fly.”

Lujack: “I don’t have any money for a ticket.”

Official: “We’ll take care of it.”

Years later, Lujack recalled that moment, saying, “It scared the hell out of me.”

Lujack, who was the oldest living Heisman Trophy winner and collegiate Hall of Famer until he died Tuesday at 98, would sit at dinner many a night in recent years at the Nest Restaurant in Indian Wells, near his longtime winter home at Desert Horizons Country Club, and chuckle at the stories of excess and celebrity in today’s college sports. He couldn’t quite fathom any of it.

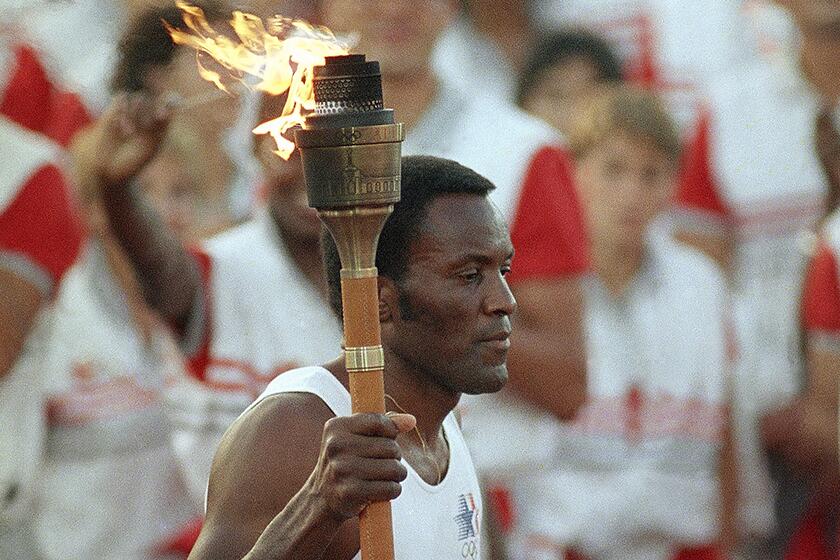

It could be could argued that Rafer Johnson lighting the torch to open the 1984 Summer Olympics is the greatest moment in 100 years of Coliseum history.

He was the fifth of six children born and raised in the small town of Connellsville, half an hour southwest of Pittsburgh, with a population today around 7,000. His father was a boilermaker on the Lake Erie Railroad and Lujack was often kidded that he should have gone to Purdue, not Notre Dame. But for Lujack, it was always going to be Notre Dame, although he considered his dream of playing there just that. Only a dream.

According to the 2018 book, “Pluck of the Irish,” written by the late Jim Hayden, Lujack’s family was so poor that they never took vacations. “In our family,” Lujack told Hayden, “sports was our only form of recreation.” For Lujack and his big old Philco radio, his specific recreation was Notre Dame football. South Bend, Ind., was only 400 miles away, but for Lujack and his family, it might just as well have been in China. Still, he had a front row seat every Saturday next to the big Philco. It was the Knute Rockne era, so heroes were easy to find, especially one named George Gipp.

Lujack was a star athlete at Connellsville High School, lettering in football, basketball and track. He was also his class valedictorian and president. But family chores came first and the Lujack family had a big garden to tend to, one that fed them all winter. One time, Johnny wasn’t quite finished with his hoeing and was too proud to ask his dad if he could stop and go to his scheduled track meet. His father sensed this and sent him running.

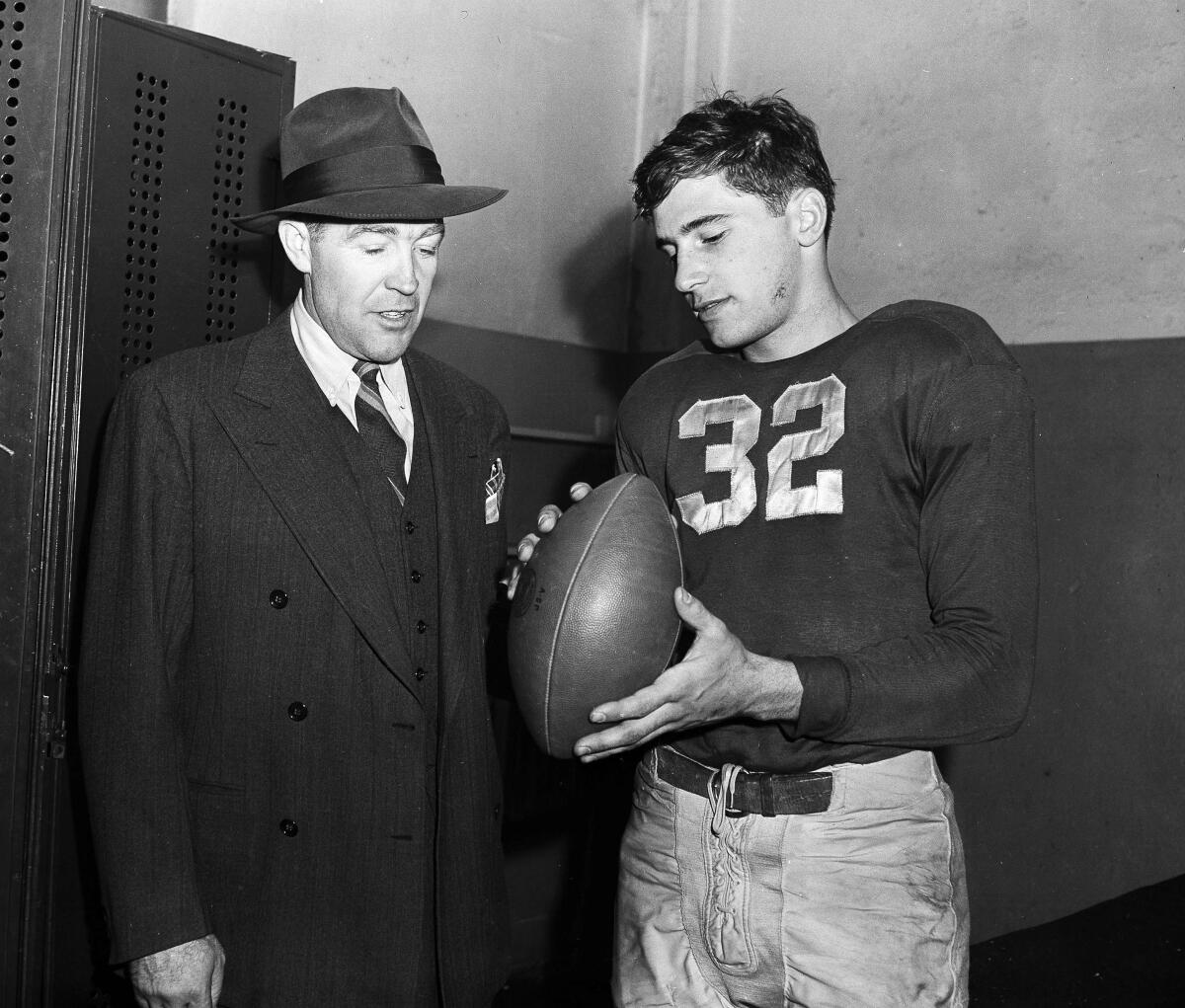

When he got to Notre Dame, thanks to a tryout in front of Irish coach Frank Leahy arranged for by a Connellsville businessman, his versatility continued. In 1943, his second full year there, he lettered in football, basketball, baseball and track. That had never happened before at the school. Nor since.

In his first baseball game for the Irish, Lujack had two singles and a triple in his first four at-bats and, between innings, dashed over to the track to throw the javelin and high jump. “The high jump was tough,” he said, “because we had those baggy baseball pants on.”

In 1943, Angelo Bertelli was the Fighting Irish quarterback. As recently as half a dozen years ago, Lujack sat at the Nest and proclaimed Bertelli: “The best thrower of the football ever at Notre Dame.” Six games into that 1943 season, Bertelli was called into military service in World War II. Lujack took over Bertelli’s unbeaten team, the Irish won the rest of their games and Bertelli, based on his six games alone, won the Heisman.

In 1944, the Navy called Lujack, and he spent two years on submarine duty, “chasing German U-Boats in the English Channel,” but with little success. “I don’t think we ever found one,” Lujack would joke, years later.

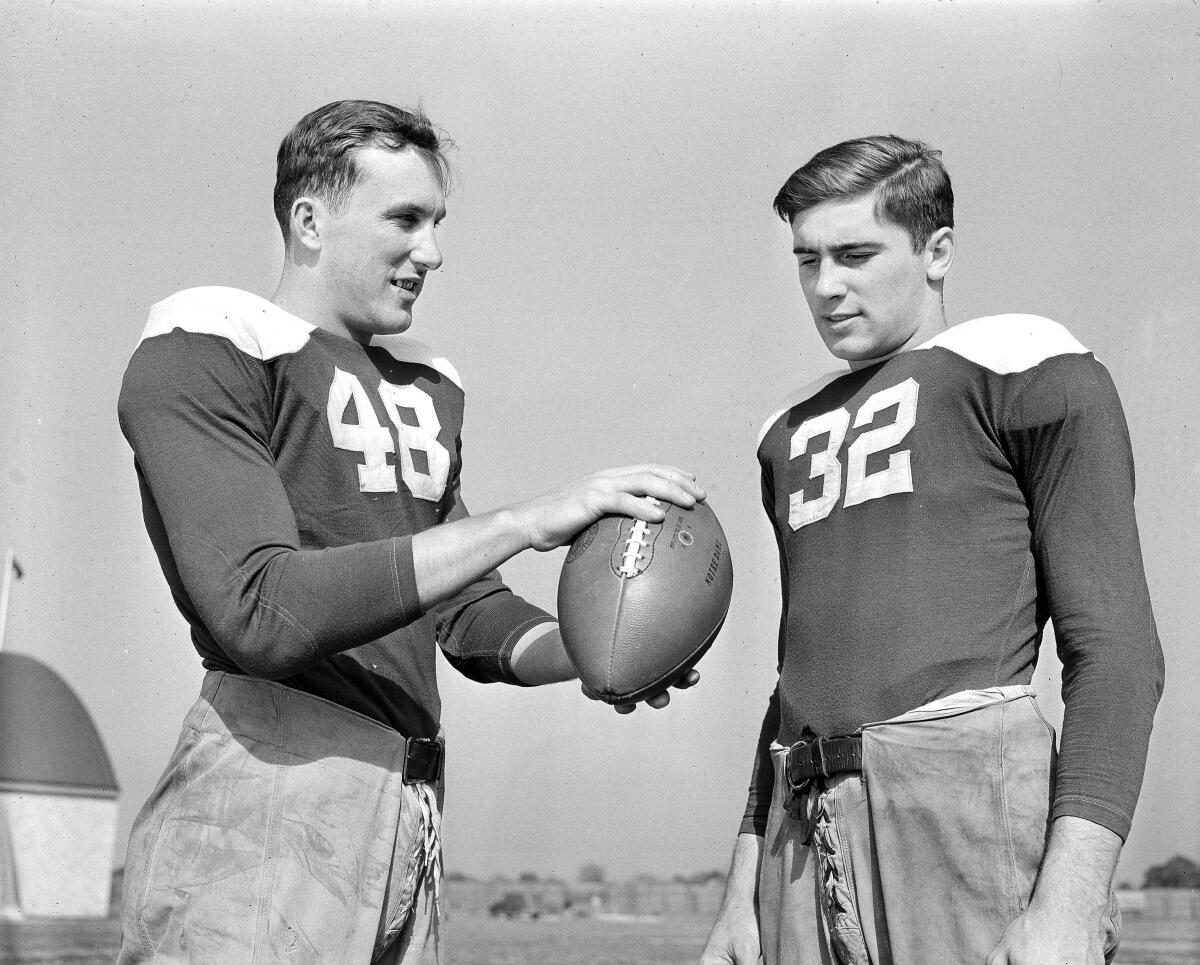

He returned to Notre Dame in 1946 and ’47, was first team All-American both years, finished his career with a 21-1-1 record and completed his collegiate eligibility standing at his locker in the Coliseum as a Heisman official told him he had won it.

Interestingly, Lujack’s offensive prowess as the Irish quarterback has long been overshadowed in college football lore by a defensive play. In the fabled 1946 Irish vs. Army game before 76,000 at Yankee Stadium, Army’s Doc Blanchard, the Heisman winner in ’45 as Lujack “chased German U-Boats,” got loose around end, with nothing in sight except the end zone. Nothing in sight, that is, until Lujack came running. He made a certain-touchdown, game-saving ankle tackle and the game ended 0-0.

Sitting around the dinner table at the Nest, Lujack would always grin and answer the same way when “the tackle,” came up. “I did what I was supposed to do,” he’d say. “I went over and tackled him. That’s why they put me out there.”

At moments like this, there was always a twinkle in his eye, showing what former Times columnist Chris Erskine once called his “Pennsylvania blarney.”

Lujack’s life after Notre Dame took several interesting turns. He went to the Bears, where he was all-pro two years and spent his time beating up on NFL teams like the Philadelphia Eagles. Four years after he joined the Bears, his Irish coach, Leahy, asked if he would come back as an assistant coach. Today, with so much NFL money involved, that request would not be made. But in the early 1950s, it was unusual but not unheard of. Lujack went back to South Bend, and when Leahy stepped down, the entire sports world expected Lujack to take over.

Lujack wanted no part of it. He said he wasn’t ready.

“I prayed every night that I wouldn’t get that offer,” he said.

He didn’t. The job went to a Notre Dame running back from Lujack’s glory years, 25-year-old Terry Brennan. Lujack had handed the ball hundreds of times to Brennan. Now his school had handed the job to the same running back. A happy Lujack went into broadcasting, the first former NFL player to get prominent network positions. He would have stayed longer behind a microphone, but when the Ford Motor Co., found out that one of the key broadcasters on NFL games they were about to sponsor also had a Chevy dealership in Davenport, Iowa, Lujack was a goner.

Lujack was the master of ceremonies for the Heisman Trophy for more than a dozen years and remained active in the Iowa dealership. His first attempt at retirement was in Florida, where he stayed for a couple of years until a friend recommended that he take a look at the California desert. He did, fell in love with it as a winter home and kept coming back for decades.

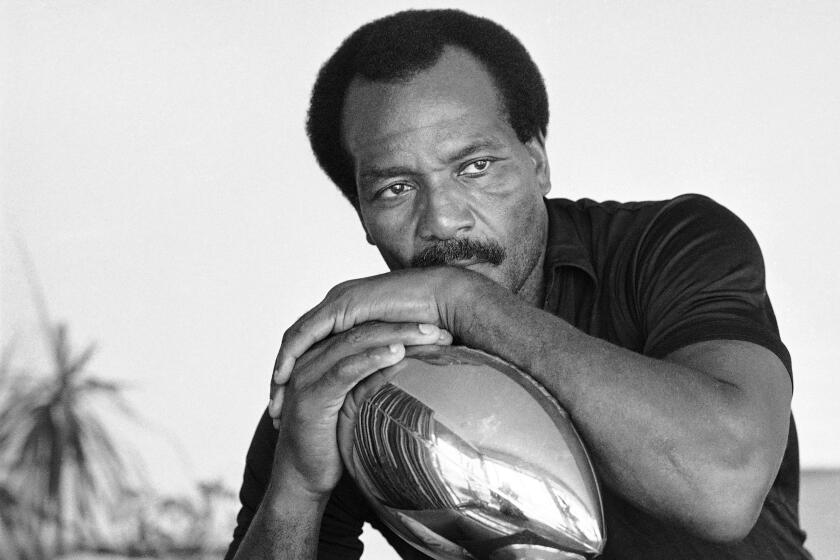

Jim Brown was certainly a U.S. icon as one of the NFL’s greatest players, an activist, an actor, an icon, but he also had difficulties in society and was not worshipped by all.

Soon, he met a prominent Notre Dame graduate named Peter Murphy, who also had a home in the desert.

“Somebody called me up, told me Johnny Lujack was moving here and asked if I wanted to have lunch with him,” Murphy recalled. “I was so excited, and when I met him, we became good friends.”

Lujack died in Florida, near where his daughter lives in Naples. His family told Murphy that he was still in pretty good shape until shortly before he died. Murphy visited him in Florida for his 98th birthday in January and said he was the same old Johnny Lujack.

Now, Murphy will help carry Lujack’s casket during Monday’s funeral services in Bettendorf, Iowa. Walking along will be the ghosts of Frank Leahy, Terry Brennan and Angelo Bertelli. Maybe even Doc Blanchard.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.