A school field trip to the room where the atomic bomb was made

Facing difficult questions at

the Manhattan Project's Hanford Site

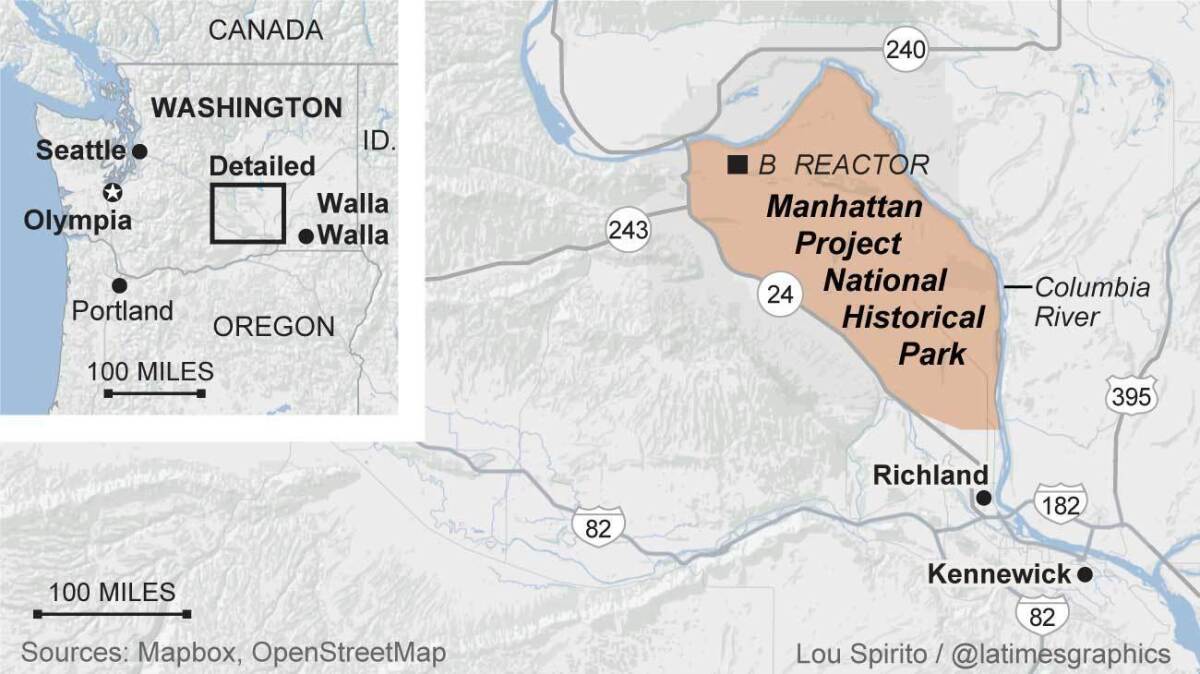

Reporting from MANHATTAN PROJECT NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK, Wash.

About the series:

The 411 units of the National Park Service are as varied as the United States itself and an incredible legacy for Americans. The Los Angeles Times Travel section continues a yearlong look at some of those units, why they matter and how the park service is working to tell this country’s story. More in the series »

On our last family road trip to the Pacific Northwest, my wife and I drove a big loop with our daughter, then 6. We hit Seattle and the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Alberta. On the way south toward Portland, we stopped at Walla Walla in southeastern Washington. Nice people, pleasant wineries.

At no point did I think, "Wait! We're only two hours from the cradle of the atomic bomb!"

But now that I've spent a few days nosing around the Hanford Site of the new Manhattan Project National Historical Park — and now that my daughter is nearly 12 — I think differently.

I'd like to do that drive again and add the Hanford B Reactor (100 miles west of Walla Walla) to the itinerary. This is the reactor that made the plutonium that powered the bomb the U.S. dropped in 1945 on Nagasaki, Japan. The National Park Service and Department of Energy are working together now to reinvent the site as a sort of classroom, a place that will get families talking about World War II, the Cold War, physics, teamwork, politics, morality and perspective.

Wait, some readers may be tempted to say. If this is a national park unit, shouldn't there be a waterfall somewhere?

Actually, no. Alongside its dozens of vast beauty spots, the National Park Service operates a growing number of parks and monuments that are more about education than recreation.

Every one of the agency's Civil War battlefields raises questions just as grave as those found at Hanford. Then there's the national monument at Pearl Harbor, where Japan's attack forced this country into World War II, and Manzanar National Historic Site, where the U.S. confined Japanese Americans for the duration of that war.

The history of nuclear weapons

“Nuclear weapon” is broad term for any weapon involving a reaction among atomic nuclei. An atomic bomb is one kind of nuclear bomb; a hydrogen (or thermonuclear) bomb is another kind that’s more powerful.

To help us understand troubles of more recent vintage, there's Pennsylvania's Flight 93 National Memorial, where the park service opened a visitor center in September.

It's no easy job, teaching American history. But it's a responsibility the park service claimed decades ago, with backing from Congress and several presidents. And for parents whose kids are ready to start confronting the world's complexities, these historical parks are a chance to do that together.

Which brings me back to southern Washington. I wouldn't make it the centerpiece of a vacation. But as a side trip? Yes.

It's a pleasure to race the tumbleweeds across the wide plains near Richland, Pasco and Kennewick, Wash., to scan the vineyards on the rolling hills and see the sun glinting off the Columbia River. And if I had the whole family along, I'd be sure to remind them that just a few miles away, cleanup workers are coping with tons of radioactive waste, the byproduct of Hanford's atomic era.

As author Blaine Harden writes in "A River Lost," this stretch of the Columbia is "a fine place to see an eagle hunt, deer graze, or fish spawn. But best not to drink the groundwater for a quarter million years."

On the floor of the B Reactor, a docent would tell us about physics, logistics and the vast power of the atomic weapon. And I would throw some grown-up questions at my daughter:

Would you drop a bomb that could kill 150,000 people? What if it might save 300,000 others? How about 3 million others?

What if you learned after the fact that you had helped build the first atomic weapons? What if you built deadly weapons that led to a delicate global balance that has lasted decades? Would that make them instruments of peace?

Up to now at Hanford, thorny questions about casualties and ethics haven't been encouraged by the Department of Energy, which owns the site and will continue to share responsibilities here. On my visit in March, I heard park service interpretive specialists nudging Hanford's docents (many of them retired Hanford scientists and engineers) to reach beyond the protons and neutrons — and still avoid personal opinions.

It was fascinating to hear. Then within days of my return from Washington, Shigeko Sasamori gave me her perspective on Hanford — a ground-zero perspective.

Sasamori was a 13-year-old in Hiroshima, Japan, on Aug. 6, 1945. As she recalls it, she spotted the American bomber in the morning sky and was pointing it out to a friend when the bomb called "Little Boy" detonated.

Her friend was killed — one of an estimated 140,000 people who died in the short term. Sasamori suffered burns on more than 25% of her body. She endured dozens of skin grafts, some paid for by charity campaigns in the U.S.

She eventually became a nurse, mother, grandmother and peace activist in the U.S.

Now 83, she lives in Marina del Rey. She told me that she likes the idea of a Manhattan Project historical park — "if they make people understand how dangerous radiation is." But if the tours focus only on physics and American teamwork, she said, "that's a horrible thing."

The message Sasamori would deliver? "Evil weapons made here. So don't make any more."

This got me thinking. What if guides in the U.S., Hiroshima and Nagasaki teamed up to tell stories together, or to build electronic links between locations? What if rangers rotated between Hanford and Pearl Harbor?

I'll hope for programming that provocative. Although I know the Manhattan Project park will never match the attendance at the parks with epic mountains and charismatic beasts, it's a great American opportunity to visit a place like this, stretch beyond our usual horizons and perhaps even learn what it's like to stand at both ends of an atomic bombing mission.

If a family can fit a day like that into a week of sixth-grade vacation, why not? On the way back south, Yosemite will still be there.

A field trip to a nuclear reactor

On a spring morning in high, dry southern Washington, a bright yellow bus rumbled to a stop in a lot at the Hanford Site near the Columbia River. The fourth-graders of Orchard Elementary School in nearby Richland, Wash., were about to see one of this nation's newest historical parks, surrounded by a valley filled with sagebrush, eagles and elk.

When the bus door opened, the kids rushed straight into a metal-and-concrete box of a building, nearly 100 feet tall, neighbored by a 200-foot exhaust stack topped by a wind-whipped American flag. Inside, looming like a Borg ship in "Star Trek," stood a massive cube of graphite bricks and aluminum tubes.

"Welcome to the B Reactor," said docent David Marsh. Then he explained how in this room American scientists made "the nuclear weapon that was used to end World War II."

"Fat Man," the atomic bomb that detonated on Aug. 9, 1945, over Nagasaki, Japan, originated here. The National Park Service, best known for its stewardship of peaks and valleys, is taking on the job of explaining how and why the U.S. built and used the deadliest weapons ever turned against mankind.

The Manhattan Project National Historical Park, established in November, is a joint effort by the park service and the U.S. Department of Energy. Besides the Hanford Site it includes Oak Ridge, Tenn. (where the enriched uranium that fueled the Hiroshima bomb was produced), and Los Alamos, N.M. (where bombs and components were designed and assembled).

Congress voted in 2014 to create this park, and park service leaders describe it as a chance to explore history that not only shaped the end of World War II but also the advance of science and at least half a century of geopolitics.

"It changed the world," said Anne Vargas, an Energy Department docent whose father worked at Hanford.

The B Reactor is the park's focal point in Hanford and the only structure most visitors will enter. The building had stood idle since 1968 and was slated for closure until the B-Reactor Museum Assn., led by retired Hanford scientists and engineers, launched a preservation campaign. The association also built models on display at the reactor and made videos detailing the science and history behind the structure.

To see it, you reserve a seat on an official tour bus and meet at the Hanford visitor center in Richland. The bus ride into the restricted site takes about an hour; visitors typically spend about two hours at the reactor with a docent. (Another tour focuses on remnants of communities that the secret project quietly displaced.) This year, for the first time, all ages are welcome.

"OMG," said one boy, facing the heart of the reactor, which is known as the pile.

"So," Marsh asked the fourth-graders, "what does a reactor do?"

"It makes plutonium to make atomic bombs," said one boy.

"What would you use to make the plutonium?" asked student Gloria Caridad.

"Uranium," another docent answered.

The reactor tours, often led by docents retired from jobs at the Hanford Site, have been a hot ticket among local families since the Energy Department started offering them in 2009. This year's tour season continues until Nov. 19.

"Does that red light always flash?" asked a mom, Colleen Lane, eyeing the equipment. (The answer was yes. The reactor is monitored full time to make sure radiation remains at "background levels.")

"Do you know what nuclear fission is?" asked docent Marty Zizzi.

Another boy raised his hand, then froze.

"I forget," he said. "We just learned it yesterday."

"We've been talking about it for a week now," teacher Liz Cronin said later. "They wanted to know why Japan bombed Hawaii in the first place. And they wanted to know why we needed plutonium when we had so many other bombs."

Enthusiasm for this trip was so high, Cronin said, that from her class of 26 kids, 18 parents volunteered to chaperone. She had room for four.

Students from a local school explore the B Reactor.

This year, for the first time, all ages are welcome at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park.

Local students react to the four-story B Reactor at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, now part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park.

Hanford's Manhattan Project story started in 1943, when Gen. Leslie R. Groves of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers chose the site for its remote location; the pure, cool water of the Columbia River; and the ample electricity generated by the nearby Grand Coulee and Bonneville dams.

Within weeks, federal officials took over more than 600 square miles of riverside land, emptied the small towns of Hanford, White Bluffs and Richland, and evicted members of several Native American tribes.

Then DuPont, the military contractor that designed and built the reactor, started construction. By 1944, 45,000 workers from across the country had raised and filled scores of mysterious industrial buildings surrounded by a secret city with barracks, trailers, Quonset hut neighborhoods (segregated by sex and race), baseball fields, an auditorium, eight mess halls and a brewery.

By September — just 11 months after groundbreaking —the B Reactor was built and began operations. By July 1945, Hanford had produced enough plutonium to power a practice bombing, the Trinity Test in Alamogordo, N.M. After the Aug. 6 bombing of Hiroshima, Japan, Hanford's rank-and-file workers learned they'd been helping to make atomic weapons. Three days later, Fat Man landed on Nagasaki, fueled by Hanford plutonium.

During the Cold War, Hanford's reactors cranked out about 67 metric tons of plutonium, fueling four decades of nuclear brinkmanship and, the Energy Department now acknowledges, creating one of the Earth's biggest radioactive messes.

You may not see signs of it from your B Reactor tour bus, but a guide may mention the Energy Department's cleanup efforts. The agency has 56 million gallons of high-level radioactive and chemical waste in storage tanks at Hanford, along with more than 80 square miles of contaminated groundwater. There's a separate Energy Department cleanup tour that takes 41/2 hours.

Confronting the B Reactor pile today is like stepping into the orchestra pit of a theater, then gazing up at a metal monster at center stage: 75,000 graphite blocks, 2,004 aluminum tubes running through them. In operation, the tubes were full of immensely hot uranium cylinders — about 64,000 of them, cooled by water from the Columbia, which eventually drained back into the river.

"The power of the place is incredible," said visiting park service ranger Denise M. Shultz, chief of interpretation and education at Washington's North Cascades National Park Complex. "I had goose bumps all over."

Just down the hall from the pile is the control room, with a central seat for the reactor operator, surrounded by dials, monitors and wiring.

"You guys know 'The Simpsons' on TV?" asked Marsh. "You know how Homer Simpson operates his nuclear reactor from his seat? This is the seat he would be in."

Besides the Hanford Site, the Manhattan Project National Historical Park includes two locations that are owned and operated by the U.S. Department of Energy.

The Los Alamos, N.M., site, which sits on a plateau 33 miles northwest of Santa Fe, includes three main areas within Los Alamos National Laboratory. At the Gun Site several buildings are associated with the design of the "Little Boy" bomb dropped in August 1945 on Hiroshima, Japan. At the V-Site two buildings were used in assembly of the Trinity Test bomb detonated in New Mexico in July 1945. The Pajarito Site was used for plutonium chemistry research during World War II, then weapon assembly in postwar years. No tours are offered, and there's no public access to Energy Department facilities. The neighboring town of Los Alamos includes the Bradbury Science Museum, which tells the history of the laboratory and the Manhattan Project. Atomic history also is a dominant feature of Los Alamos walking tours. Also in New Mexico but not included in the Manhattan Project park are the Army-controlled White Sands Missile Range (which includes the Trinity Test site, open to the public twice yearly, and the adjacent White Sands National Monument.

The Oak Ridge, Tenn., site, a city and industrial complex 25 miles west of Knoxville, was home to more than 75,000 people. Locations there include Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the X-10 Graphite Reactor (which produced small amounts of plutonium), the Y-12 Complex (home to the electromagnetic separate process for uranium enrichment) and the site of the K-25 Building (where gaseous diffusion uranium enrichment technology was pioneered). Uranium for the Hiroshima bomb was enriched in the Y-12 Complex and K-25 Building. Those sites are included on a DOE bus tour (open to U.S. citizens only) that's offered March through November, two to five days a week. The tour is included in the $5-per-adult entrance fee to Oak Ridge's American Museum of Science & Energy (amse.org). Since early this year park service rangers have been answering questions at the museum.

Later, somebody pulled the kids together for a group picture and hollered, "Smile and say, 'B Reactor!'"

Nobody asked about the atomic bombs' effects in Japan. Nor were death or injury statistics offered. In fact, the 28-page document that docents use as their main source doesn't include information on deaths and destruction.

But now, said Kirk Christensen, manager of B Reactor preservation for Energy Department contractor Mission Support Alliance, "we're going to have these conversations."

With about 12,500 visitors expected this year, the Energy Department is footing the costs of the Hanford tour program while the park service waits to see how much funding the next federal budget will include. Tracy Atkins, interim superintendent of the Manhattan Project park, said she would make her first hires soon.

The park service will spend the next 18 to 24 months developing the park's first round of interpretive materials, drawing on input from scholars and community members in New Mexico, Tennessee, Washington and Japan. A separate approach for kids younger than 12 will probably be included, Atkins said.

The park service may also print some materials in Japanese, Atkins said, but "we can't change everything overnight."

Tips for visiting Manhattan Project National Historical Park in Washington

How to get to the Hanford Site: The interim visitor center for the Manhattan Project National Historical Park at the Hanford Site — where bus tours to the B Reactor begin — is at 2000 Logston Blvd., Richland, Wash., 15 miles west of the Tri-Cities Airport in Pasco, Wash.

Best time to visit: Late spring and early fall, when afternoon highs are usually below 90 degrees.

How to visit: Reserve a seat on a free four-hour bus tour (there's no private vehicle access) from the visitor center. Mondays through Saturdays through Nov. 19. Saturdays book up the fastest. Info: manhattanprojectbreactor.hanford.gov

Accessibility: The B Reactor building is fully accessible for those with walkers and wheelchairs. With advance notice, tour organizers can deploy a bus with a wheelchair lift.

Children: Visitors of all ages are allowed. Authorities say there are no unusual radiation levels on the tour route, but the Department of Energy does require parents of minors to sign a liability release acknowledging that the B Reactor is "a radiologically controlled area" with potential risks and industrial hazards.

Sleep: Marriott Courtyard Richland Columbia Point, 480 Columbia Point Drive, Richland; (509) 942-9400. Pleasant location. Rooms for two typically $150-$175.

Eat: Anthony's at Columbia Point, 550 Columbia Point Drive, Richland; (509) 946-3474. Seafood and steaks in an airy dining room with marina views. Main dishes $19-$40.

More info: Manhattan Project National Historical Park.

Twitter: @mrcsreynolds

christopher.reynolds@latimes.com

Follow our adventures: Facebook | Twitter | Pinterest

Additional Credits: Digital design and production: Sean Greene.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.