In India, an expired visa means a lot of days of frustration, nights fretting about getting home

- Share via

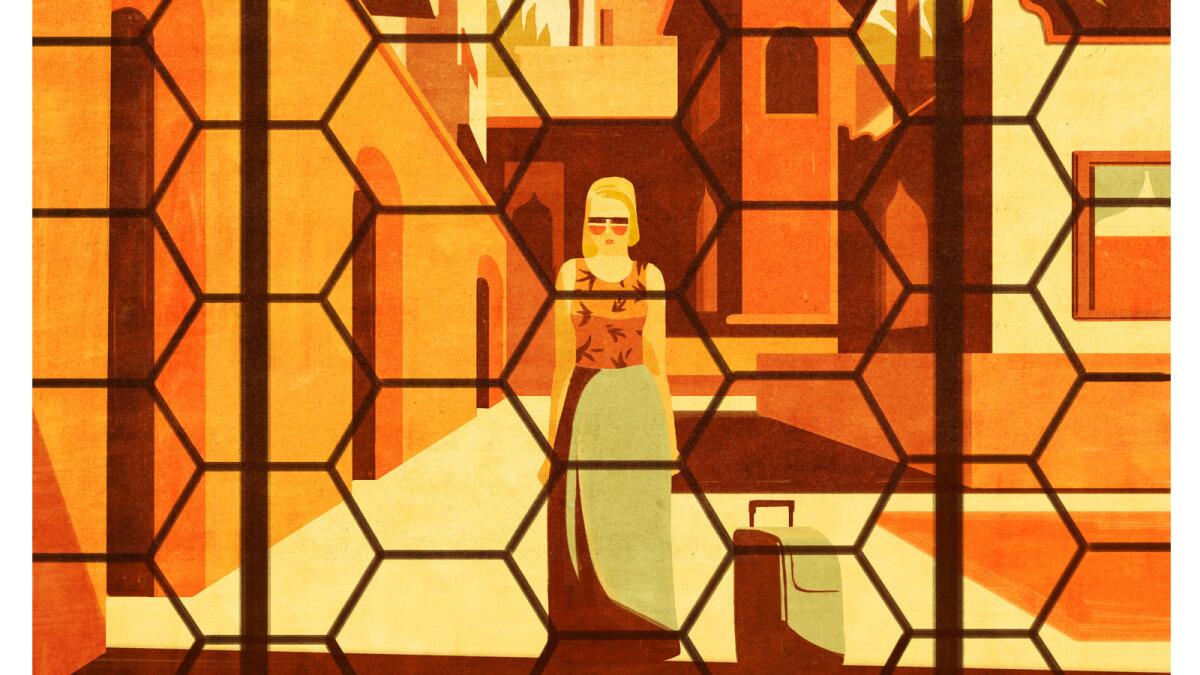

Reporting from CHENNAI, India — I had just experienced nearly five weeks of serenity in Auroville, a homegrown spiritual community in India. It was the Tuesday before Easter, and I was ready to return home for family festivities when my trip took a detour.

One minute I was in line at the Chennai airport waiting to pass through immigration. The next minute officials calmly commanded Air India baggage loaders to remove my checked suitcase from the plane.

I stood in shock and disbelief in an airport office pleading with a bureaucrat. My mother died not long ago; I must get home.

There are procedures, she said, a word I heard repeatedly in the coming days. Someone wrote in my notebook, BOI (Bureau of Immigration), Shastri bhavan, Haddows Road, Nungambakkam.

“Go there tomorrow morning,” she said, dismissing my questions.

My tourist visa had expired three days earlier, a fluke of arithmetic and the Catch-22 procedure of having to apply online for a 30-day visa before knowing which flights could be booked using miles.

I had no idea that there was a problem until, on my way to India, a German immigration officer in Frankfurt pointed out that my visa would expire before the date of my return flight.

No worries. I had overstayed visas twice in Argentina, paid a fine, and was on my way.

When I arrived in Auroville, I exchanged emails with immigration and asked what to do. The emails were canned responses.

Detained in Turkey for a visa violation, all alone. Would I ever get home? »

I finally asked what would happen at the airport when I wanted to leave. The reply: “You will not be allowed to enter the country.” I wrote back, “But I’m already in the country,” and concluded I would pay a fine — no big deal.

I know now that “enter” should have been “leave,” an incorrect word choice made by the sender whose first language probably was not English.

So I took a room at the Radisson Blu in Chennai. My laid-back lodging in Auroville had cost me $234 for nearly five weeks; this golden cage cost $150 a night.

The staff was friendly and solicitous, maybe because of the EV — expired visa — stamped on my passport. Indian hotels are not allowed to lodge foreigners with expired visas. That was a problem, but they mercifully allowed me two nights and seemed as bewildered as I was about my predicament.

Mahesh, a taxi driver who became my guide and chauffeur, took me daily to the Bureau of Immigration, as grimy and dingy as any government office.

It was hard to believe this was the same India I had just experienced in peaceful Auroville with its dazzling birds, tropical vegetation and women in rainbow-colored saris.

Where was the amazing color, light and tranquillity? The clerks’ only words to me were “Sit down. Sit down.”

My visa would expire before the date of my return flight

— Camille Cusumano

Other supplicants sat in quiet fear. A woman departed in tears. I watched a man leave with a look of despair.

I left with a small square of paper that a harried officer thrust at me. “Tourist Visa Overstay Exit,” it said, and it listed six requirements I needed to satisfy before they would consider letting me leave the country.

It could take weeks, a woman near me said jocularly as if sharing insider knowledge.

A daunting to-do list

I had reveled in the rural beauty of Auroville, but now I slept little, racked up unanticipated debt and attacked the list of documents I had to compile before I could leave.

In a windowless basement room at the Radisson, I communed with business machines making copies, filled out the online exit application — all the while coping with numerous computer freezes — and wrote “a detailed explanation for overstay.”

Mahesh took me to the appropriate vendor for my mandatory mug shots, an entire day’s effort in this densely populated city.

Radisson and my Auroville hosts had to fill out official Form Cs, declarations of dates and details of my lodging.

Finally, I required a “Latest Police Clearance Certificate.” Because I didn’t have an “earlier” clearance I assumed it did not apply to me.

Of course it did.

Mahesh and I made several visits to two police stations. He spoke rudimentary English but fluent Tamil, the local language. I spent hours each day in the back seat of his air-conditioned taxi, anxiously watching the streams of cars and motorbikes.

Mahesh and I bonded in our quest to get me home. He took charge of my case, but I often sensed his own confusion.

Now he was the one to tell me to “sit down, sit down” as he spoke in Tamil to officials.

I felt like Ilsa and Victor Laszlo in “Casablanca,” desperate for an exit visa. I didn’t need Peter Lorre; I had Mahesh in his spanking-white uniform and peaked cap.

On the move

I circulated through two other hotels during the week. At the Hotel Chandra Park in the funky Egmore district, the clerk was near tears as he told me, “Madame, I cannot let you stay here.”

I was near tears begging. His compassion superseded his concern about the Bureau of Immigration, and I was allowed two nights.

That took me to Saturday, the day before Easter, when I hopped a bus to Mamallapuram, a small beachside town and UNESCO World Heritage Site. I persuaded the upscale Grande Bay to lodge me for one night, preempting trouble by telling the receptionist that I was in the process of obtaining my exit visa.

Every time I walked through the lobby I expected to be accosted and told to leave due to my red EV.

Easter now, and I returned to the Radisson, because it was near the offices I needed. I hoped it would take me back.

It was hard to believe this was the same India I had just experienced in peaceful Auroville

— Camille Cusumano

Ahmed, a compassionate reception clerk in a smart blue-and-black suit, told me it could not.

Desperate, we called the emergency number for the U.S. Consulate, and I spoke to Benjamin. He told Ahmed that the consulate would email an official request to lodge me, saying that I was in the process of procuring my exit visa.

The Radisson agreed to take me back.

Before we hung up I asked Benjamin, “What would happen to an Indian tourist who overstayed a visa by three days in the U.S.?”

He replied: “Nothing.”

Monday, Day 7. Mahesh picked me up at 8 a.m. so I could get my police clearance. At the station for the third time, a woman in a sari smiled in recognition.

She did a routine frisk of my khaki skirt inside a makeshift pole-supported tent. Mahesh and I went through metal detectors. The police, dressed in jeans and sport shirts, were surprisingly congenial and gregarious.

It took a few hours to complete my fingerprinting and paperwork while the presiding officer joked about kooky New Agers in Auroville.

I laughed, I cried, I hugged one of the police.

Almost there — almost

Tuesday, Day 8. If the BOI accepted my six documents, an inch-thick packet, I would be on a flight home at midnight. We were almost there — it’s a juggernaut of a drive — when I groaned. I had left my passport at the hotel.

We called the Radisson and I explained to Ahmed where in my suitcase to find my passport, which someone brought to us at the BOI.

Mahesh handed in my thick “hot sheet” to a clerk, and we sat quietly for five hours.

At last, just before 5 p.m., closing time at the BOI, the clerk called us to his window. In one agonizingly long but anticlimactic moment he told us where to pay the $90 fine.

Mahesh and I smiled. We knew I would be on that midnight plane.

He drove a new route to the Radisson, taking me through an affluent area where government officials lived. For the first time, I saw some beauty and elegance in Chennai.

Mahesh wanted to stop at a friend’s boutique, and I could tell it was so I could spend some dollars. Despite being set back nearly $2,000 for my unplanned stay, I felt lightheaded and reckless. Who knew freedom is a drug?

I bought marble Ganesh statuettes, the elephant god of India, to give to my five sisters.

In fairness, it was my responsibility to be aware of timing and the conflict between my visa’s expiration date and my departure date. Maybe I was delinquent.

Still, I resented India for what seemed to be a senseless waste of time, effort and money. The vexation would stay with me awhile.

Who knew freedom is a drug?

— Camille Cusumano

But eventually I considered the teachings I learned in India, the birthplace of Gautama Siddhartha, the Buddha.

Resentment, he taught, is one of three poisons to happiness. (Grasping and delusions are the two others.)

I focused on Mahesh, Ahmed and the policeman, all of whom let me hug them; the clerk at Hotel Chandra who swallowed his fear and risked a penalty to help me; and the last night at the Radisson when I joined the young wait staff in some sort of Indian Macarena.

And one more thing: The clerk at the BOI smiled sweetly at me and wished me well. The crack in his stolid countenance told me he was happy for me — that the procedures took only eight days and were not meant to punish me, only to allow him to do his job.

MORE FROM TRAVEL

In old-world Croatia, here are four trendy towns worth visiting

On the Spot: What to do if you’re in trouble overseas

If you’re worried about illnesses, travel insurance may not be your best investment

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.