Feet wet and thoughts adrift, a handful of us slouched on wooden chairs in the middle of the Big Sur River, shaded by tall trees, surrounded by gently moving water.

“I wish I could always live like this!” said Catie Bryant of Seaside, Calif.

“You can put your feet in the river and listen to the birds. Why would you not?” said Cori Graves of Portland, Ore.

We had nature right where we wanted it, with the Big Sur River Inn’s bar just a few steps away. And this was only possible because of Highway 1, the Mother Road of California tourism, begun a century ago, completed in 1937 along a forbidding coastline of redwoods, rocky slopes and crashing waves.

I’d put together this road trip with two goals: to learn what a traveler should know about Big Sur now and to look for hints of those days in the 1920s and ’30s when the coast road opened and the world rushed in.

I already knew some bad news: The Lucia Lodge restaurant and store, a landmark since 1937, burned down one night in August 2021. The lodge’s 10 clifftop guest rooms are still rentable, but the restaurant’s rebuilding timetable is unknown.

Get ready to explore with our list of the best places to go and things to do in California during fall, including museums, parks, markets, and more.

Meanwhile, room rates are up and campsites are hard to come by. Fearing that travelers will start to sleep in their cars along the highway, Monterey County’s Board of Supervisors in July boosted the fine for that from $200 to $1,000 per night.

Fortunately, I found plenty of good news along the coast road too. And I’m not just talking about the holy granola or the views from the Bixby Creek Bridge.

Building the road

It was 1922 when the road crews began connecting San Simeon to Carmel. That meant cutting through woods and slopes that were the unchallenged domain of the native Esselen, Rumsen and Salinan people until Spanish troops arrived in the 18th century, the homesteaders in the 19th.

Thwarted by the steep, rocky topography and the arrival of the Great Depression, the highway project inched forward, convicts from San Quentin supplying much of the muscle. The crews raised 29 bridges, dynamiting ton upon ton of the Santa Lucia Mountains into the sea.

“My coast has been defiled and raped,” lamented writer and Big Sur devotee Jaime de Angulo. The poet Robinson Jeffers, who lived in Carmel, was just as opposed. In his 1937 poem, “The Coast Road,” he described a horseman on a ridge, happening upon the bridge builders.

“He shakes his fist and makes the gesture of wringing a chicken’s neck, scowls and rides higher,” wrote Jeffers.

But those naysayers were the minority. When the project was finally completed in the summer of 1937, you could drive the 71 miles between San Simeon and Carmel in a leisurely, jaw-dropping day. Electricity and phone service were still years away, but now a motorist could witness what Jeffers had seen on foot: one of this planet’s greatest confrontations between land and sea (dynamite damage notwithstanding).

All these years later, driving this stretch of Highway 1 is still one of the most amazing things you can do in California.

Along the way, you’d be derelict if you didn’t catch a sunset from the deck of Nepenthe restaurant (mile marker 44, opened 1949). You might also nip by the nearby Henry Miller Memorial Library (founded in 1981) to be reminded of those days in the 1940s, ’50 and ’60s when Henry Miller was here typing furiously in one cabin, Jack Kerouac was drinking heavily in another; when Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth were buying a vacation home, then ditching it and each other.

Some years after that, an excitable young writer named Hunter S. Thompson showed up and got hired (and then fired) as caretaker of the seaside property that is now the ever-so-mellow Esalen Institute.

Highway 1, Thompson told readers in a 1961 Rogue magazine story, “climbs and twists along the cliffs like a huge asphalt roller coaster; in some spots you can look eight-hundred feet down to the booming surf.”

Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of Caltrans, the highway has proved to be about as reliable as Thompson was as a caretaker. Amid fires, storms and landslides, the Big Sur portion of the road has been shut down dozens of times through the decades, sometimes for weeks, sometimes for a year or more.

But when it’s open — as it has been since late April 2021 — it’s priceless. And it sustains a hardy, quirky, growth-averse community of restaurants, shops, lodgings and an estimated 1,786 residents.

Moving among them, I measured my journey using the highway’s roadside mile markers, whose numbers get higher as you continue north through Monterey County.

Mile marker 11: Yurt people

My first stop was a thoroughly 21st century place. Treebones has offered yurts and glamping since 2004, attracting a prosperous, stylish crowd happy to pay $360 to $480 nightly. It routinely books up months in advance.

Far less money or planning is required, however, if you drop into Treebones’ Lodge Restaurant for lunch. You can have a tasty salad, as I did ($14, grown on-site), while sitting at the patio gazing down at the slopes, the tops of yurts and the vast Pacific.

You may be tempted to walk the grounds — forget it. I tried and was gently ejected. Overnight guests only.

Mile marker 23: Monks seeking company

“Holy Granola,” says the roadside sign. It leads to a revelation: Since 1958, the Catholic Church’s Benedictine order has been quietly running a 899-acre hermitage on the high slopes above Gorda.

Besides praying in silence and making granola ($12.98 per pound), these monks rent out rooms with views. The New Camaldoli Hermitage rents out 17 lodgings to the public, some single-occupancy, some double-occupancy, for $135 to $385 nightly.

You have to be quiet, of course, but in exchange you find staggering views. You’re also entitled to three meals daily and you may pray with the monks, if you like. The writer Pico Iyer has been a regular for more than 20 years. Even if you only leave the highway to buy granola, the two-mile, switchback-filled drive up to the hermitage, about 1,300 feet above sea level, is a memorable affair in itself.

From the mountaintop, and from just about any vantage point in Big Sur, you’ll see pampas grass arrayed along the slopes like an army of featherdusters. It’s pretty — but none of that was here in the 1930s. It’s a species that someone apparently imported in the 1960s. Motorists and hikers may be unwittingly spreading seeds.

Mile marker 36: The famous falls

This is where you’ll find 80-foot McWay Falls, Big Sur’s most iconic water feature, the star of Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park. You can reach the viewpoint easily on the half-mile Waterfall Overlook Trail. But bear in mind that nobody saw this scene this way in 1937.

When Highway 1 opened, this was private property. Someone‘s house stood at the viewpoint and the falls fell straight into the ocean. In 1962, Helen Hooper Brown donated the property to the state park system. Soon after, the house was dismantled. Then in 1983, after massive storms, highway reconstruction dumped tons of sand near this cove and created the beach beneath the falls.

But — it’s a cruel world, Instagrammers — there’s no access to that beach. The state parks website warns that any attempt to get there “is a citable offense. This area is extremely hazardous.”

Mile marker 43: Norwegian woodwork

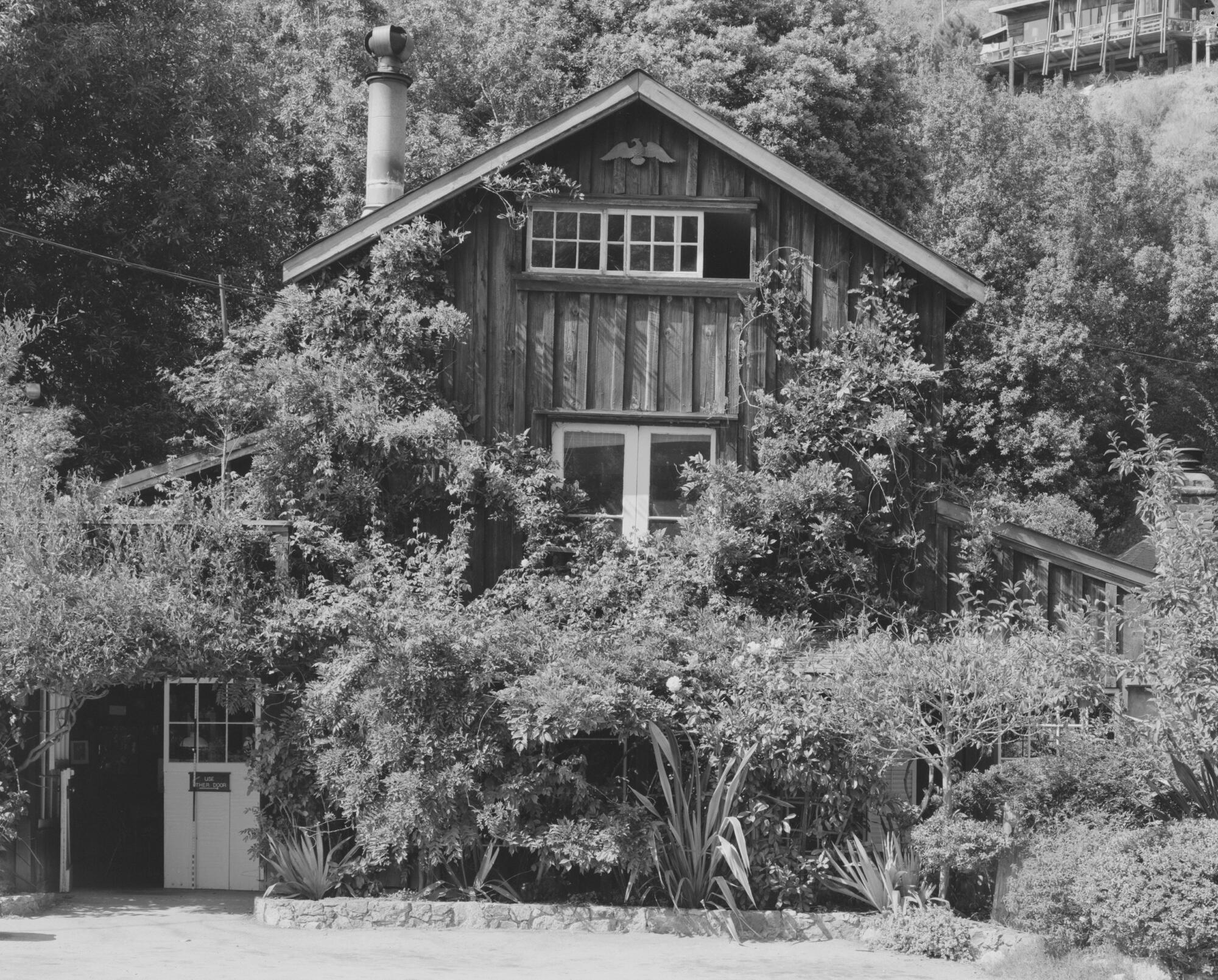

As you approach Castro Canyon, Deetjen’s Big Sur Inn pops up like a weathered redwood hallucination.

Half a dozen smallish buildings huddle there, and when you arrive, a plume of smoke may be rising from the old stone fireplace, and perhaps a faint strain of classical music will be leaking out from the restaurant. It’s enough to make you suspect that Thomas Kinkade, he of the perfect cabins and beckoning lampglow, was a realist painter after all.

This 20-room lodging and restaurant is the work of Helmuth Deetjen, an immigrant from Norway, who used his native building methods to craft the compound, which began as a tent home in the early 1930s and evolved as Deetjen worked with his wife, Helen, and business partner Barbara Blake.

For a while in the mid-’30s, general manager Matt Glazer told me, the inn was where the pavement stopped in Big Sur — “the end of civilization” for southbound drivers.

By 1936 Deetjen had put up a barn, which is now the main dining room.

Gradually, the inn earned a following as a romantic getaway. This was despite the thin walls in the board-and-batten structures and perhaps despite Deetjen, who was a bit of a loner. Hunter S. Thompson wrote in 1961 that Deetjen “looks more like a junkie than a lot of real hopheads.”

Yet Deetjen ran the inn for decades. And before he died in 1972, he arranged to leave it to a nonprofit entity that would run the place as Deetjen did, resisting modernity.

Thus, the Norwegian vernacular architecture has never seen a design update. The five units in the Hayloft Hostel building share two bathrooms. No televisions, phones, Wi-Fi or reliable cellphone reception in guest rooms. Reservations, $100 to $435 per night, are taken by phone only.

The whole enterprise nearly collapsed in 2020, amid COVID-19 and tensions between the two nonprofit organizations that jointly owned and ran Deetjen’s.

Happily, a reorganization and fundraising effort were fruitful, and when Deetjen’s reopened in 2021, it saw the same surge in visitors that has kept all of Big Sur busy. Early this year, the inn reopened two units damaged by a fallen redwood in 2017.

I’ve stayed there several times. This time I had breakfast and found it charming as ever. The old man’s favorite classical music was playing, as it does each morning. Eggs Benedict remains a specialty. In an oil portrait on the wall, Deetjen sports a beret and looks down, perhaps a bit skeptically, at his 21st century guests.

Mile marker 45: Baked goods and gas

Nearly a decade before the coast road went through, in 1929, one of the area’s pioneer families had opened the Loma Vista Inn. It had a diner and a gas station.

Today, the Big Sur Bakery occupies the inn’s original wooden building and serves tremendous baked goods — order the prosciutto buns — along with breakfast and lunch (five days a week) and dinner (four nights a week). Around the bakery sprawl the Loma Vista Gardens, which include Mother Botanical and a pop-up art gallery in an old carriage-house barn.

And yes, there’s still a gas station, priced at about $7.70 a gallon when I passed through. That was about the same as I found at the Big Sur River Inn and Ragged Point gas stations, far less than the $9.29 being charged at the station in Gorda.

Mile marker 47: From homestead to state park

Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park is rich in a rare Big Sur commodity: flat land. That may be why this acreage was grabbed up in the 1880s by John and Florence Pfeiffer, two of the region’s early homesteaders. They farmed, ranched and in 1908 started taking paying guests.

Then more guests started coming. And as plans for the highway took shape, a developer from Los Angeles is said to have offered to buy a chunk of Pfeiffer’s land. (If this story were a staged melodrama, the hisses would go here.)

Instead, in 1933, Pfeiffer sold 700 acres to the state at a below-market price, which is how Big Sur got its first state park, now grown to 1,006 acres. That territory includes a pool, softball field, the Big Sur Lodge, 61 guest rooms and trails leading to the Valley View overlook and Pfeiffer Falls. (The area’s other state parks weren’t created until decades later.)

I was sorry to find Pfeiffer Falls trickling feebly after many months of little rain, but the Valley View, with the Point Sur Lighthouse in the distance, is still a great, green panorama.

“I’ve been coming for 40 years,” Oscar Pabon of Los Angeles told me on the trail. He had reserved his park campsite six months before and counted himself as “really lucky” to have landed it. “Nature is better when you’re camping,” he said. “And glamping is not camping.”

Mile marker 49: Apple pie and wet feet

Nobody knows exactly when people started dragging the Big Sur River Inn’s chairs into the water, but the inn goes back to 1934.

That’s when Ellen Pfeiffer Brown, a descendant of the homesteading Pfeiffer family, started serving meals. Since her specialty was apple pie, she called her place the Apple Pie Inn.

That history “influences just about everything we do today,” said Rick Aldinger, general manager of the inn.

As other family members took turns managing the venture, a gas station and a store were added and some of the inn moved across the highway. The name changed to Redwood Camp, then River Inn.

Nowadays, a weathered stone fireplace dominates the dining room, having stood for more than 80 years. Ellen Brown’s apple pie recipe is still on the menu (though Aldinger says he prefers his mother’s recipe).

Under the Perlmutter family, owners since 1988, the River Inn has grown into a summer juggernaut, with legions of diners gathering on the restaurant deck and dozens dragging chairs into the water.

Why would anyone spend a whole day driving to reach a private, unincorporated community along a 10-mile stretch of coastline? There’s no other place like it.

Under that wear and tear, the chairs last only three or four seasons, Aldinger said, and the staffers are forever making replacements in a workshop on-site.

I had a hearty dinner and slept in one of the inn’s motel rooms ($345 per night after taxes), which had pine paneling and a big wall-mounted television.

“We’re learning. That was a mistake,” Aldinger told me later. By next summer, he said, those motel room TVs may be gone, preserving a more woodsy look. (The inn provides Wi-Fi in guest rooms but not public areas.)

Mile marker 60: You know this bridge

The Bixby Creek Bridge, the region’s most iconic man-made feature, was the northernmost stop on my route, and it’s the one place you’ll recognize even if you’re a first-timer.

It was completed in 1932, spanning 714 feet, 260 feet high and just 24 feet wide. Visiting now, you notice that narrowness, along with the frequent traffic snarls nearby, as tourists park haphazardly and walk heedlessly.

You and I are better than that, of course. We park legally, walk carefully and do not court death with our clifftop selfies.

We might, however, take a few steps inland along the dirt shoulder of Coast Road. From there, as you look back toward the span, there’s another cool photo angle that many people miss.

Mile marker 44: What if?

After three days it was time to turn and head south to home. But there was time for two last stops on the way.

First, 9 a.m. juice at Nepenthe’s Cafe Kevah, where you can watch the rising sun burn off the morning fog.

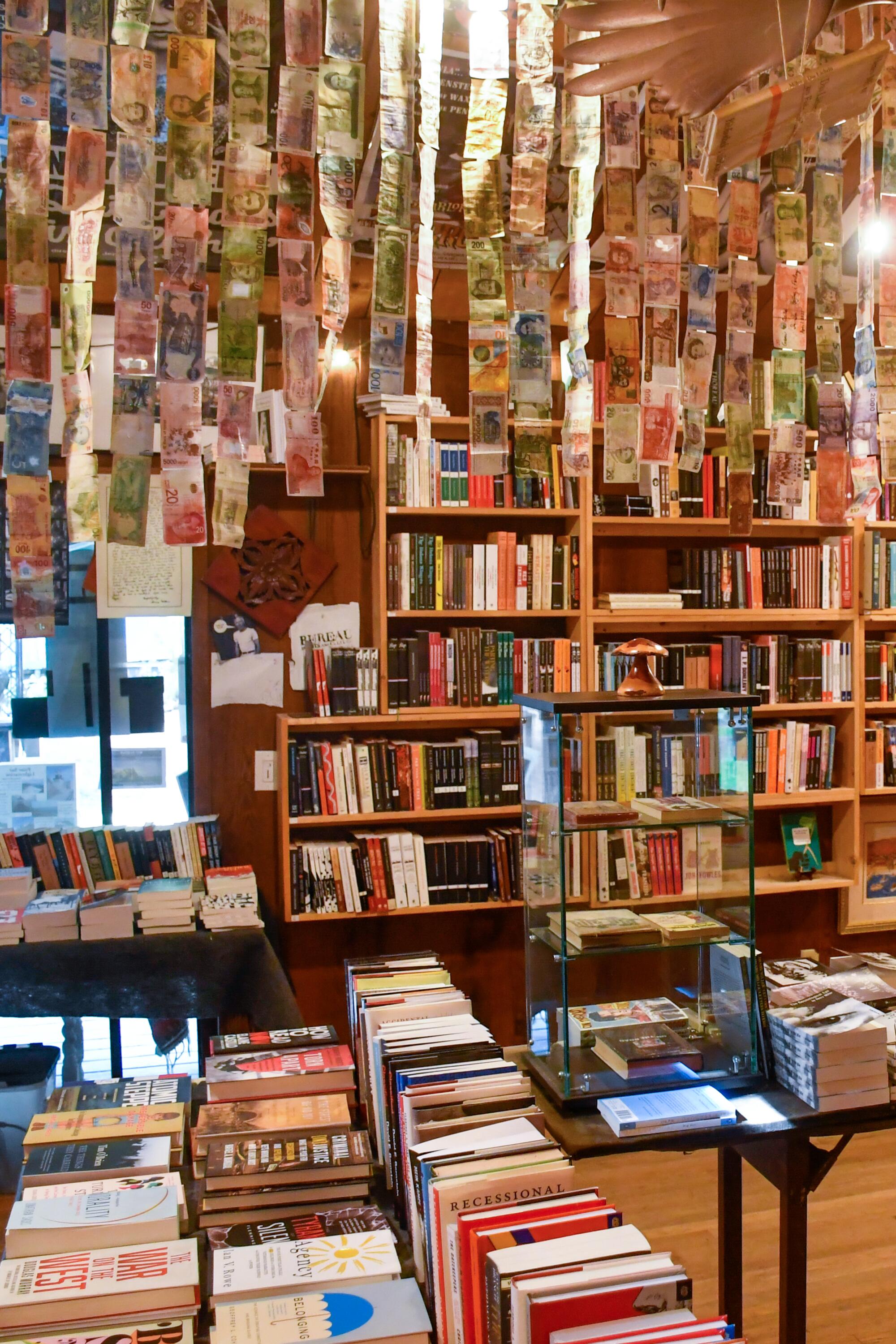

Then I dropped into the Henry Miller Memorial Library, a lively cultural center whose motto is “where nothing happens.”

This is false. The executive director, Magnus Toren, was holding court when I stepped in. I mentioned the highway and the old Jeffers poem.

“Robinson Jeffers was right,” Toren said. “Can you imagine if the highway had never been built? We’d be standing in the middle of the most amazing nature reserve in the world. But now it’s too late to chase us all out of here.”

If you go

The Big Sur portion of Highway 1 begins at Ragged Point, 245 miles northwest of Los Angeles City Hall, about 15 miles northwest of San Simeon. From Ragged Point it’s about 76 miles north to Carmel.

Where to sleep

Treebones, 71895 Highway 1, is known for its yurts, priced at $360 to $480 nightly. Also available: glamping and a handful of campsites. Lunch is served noon to 2 p.m. For dinner in the Lodge restaurant or Wild Coast sushi bar, you need a reservation.

The New Camaldoli Hermitage, 62475 Highway 1, offers nine single-occupancy units in a “retreat house” (shared shower and kitchen) and five cottages, three of which are double-occupancy. Rates are $135 to $385 nightly; no radios, musical instruments, loud voices or children under 16.

At Gorda Springs Resort, 72801 Highway 1, don’t pay $9.29 for a gallon of gas. But the $9 clam chowder at the Gorda Springs Whale Watchers Cafe was tasty. And the rustic cabins on the hill do have ocean views. Consider the Palm House ($225 to $350 nightly).

Big Sur River Inn, 46800 Highway 1, includes 22 rooms, a restaurant, gas station and store. Motel rooms $195 to $395, riverside suites usually $325 to $525.

Deetjen’s Big Sur Inn, 48865 Highway 1, rents 20 rooms, typically $100 to $435. Its restaurant serves breakfast and dinner, reservations recommended, but closes Wednesday and Thursday. The inn and restaurant likely will close Jan. 1 through Feb. 28 for infrastructure work.

Fernwood Resort, 47200 Highway 1, has motel rooms, cabins, campsites, platform tents, a tavern and a general store. It doesn’t look fancy or historic but dates back to 1932. The 12 motel rooms rent for $180 to $255 nightly. (Ask for Room H, which has a hot tub on its private patio.)

Glen Oaks Resort, 47080 Highway 1, born in 1957 as a basic motel, has morphed into a 20-acre upscale property, fronted by a carefully landscaped boutique hotel (a.k.a. the Adobe Motor Lodge, with November rates of $310 to $435 nightly) and Big Sur Roadhouse diner (breakfast and lunch). Cottages and cabins, set farther back, are priced at $560 and beyond.

Alila Ventana, 48123 Highway 1, opened in 1975 and sold many times since then, is one of Big Sur’s two most luxurious, costly resorts: 59 units, adults only, typically $1,800 nightly and beyond, meals included, glamping also offered. Its Sur House restaurant is open to nonguests.

The Post Ranch Inn, 47900 Highway 1, opened in 1992, includes striking design, 39 rooms, adults only, typically $1,650 and beyond. Its Sierra Mar restaurant is open to nonguests.

Big Sur’s state park campsites (including Limekiln, Julia Pfeiffer Burns, Pfeiffer Big Sur and Andrew Molera state parks) typically book up to six months ahead, as do its national forest campsites (including the popular Kirk Creek and Plaskett Creek campgrounds). Fees are usually $30 to $50 nightly.

Big Sur’s private campgrounds charge more than park campgrounds but usually have more availability at short notice. At Big Sur Campground & Cabins, you might pay $100, plus a $25 “resort fee,” for one midweek night in November. Summer rates can be twice as high.

Where to eat

Most of the lodgings above also include restaurants. Here are a couple more.

Nepenthe, 48510 Highway 1, is open daily from 11:30 a.m. to 10 p.m. Its offspring Cafe Kevah is open 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., weather permitting. The Phoenix shop beneath Cafe Kevah is open 10:30 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Big Sur Bakery, 47540 Highway 1, is open Wednesday through Monday, 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. Breakfast and lunch are served Wednesday through Sunday (check website for hours), dinners Wednesday through Saturday.

Don’t miss

Pfeiffer Beach. This mile-long, wind-raked beach and the Keyhole Rock boulder configuration, controlled by the U.S. Forest Service, are at the bottom of narrow, two-mile Sycamore Canyon Road with only about 60 parking spaces ($12 per car). There’s no sign on Highway 1 to tell motorists it’s there. Instead there’s a warning: “Narrow road, no pedestrians, no RV’s, no trailers.” If you can get there on an off-season weekday, it’s worth a try.

Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park, which comes up at mile marker 47.2 on Highway 1, has hiking and lodging but no beach access. Entrance is $10 per vehicle.

Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park, which includes McWay Falls, is near Highway 1’s mile marker 35.8, 37 miles south of Carmel. Entrance is $10 per vehicle.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.