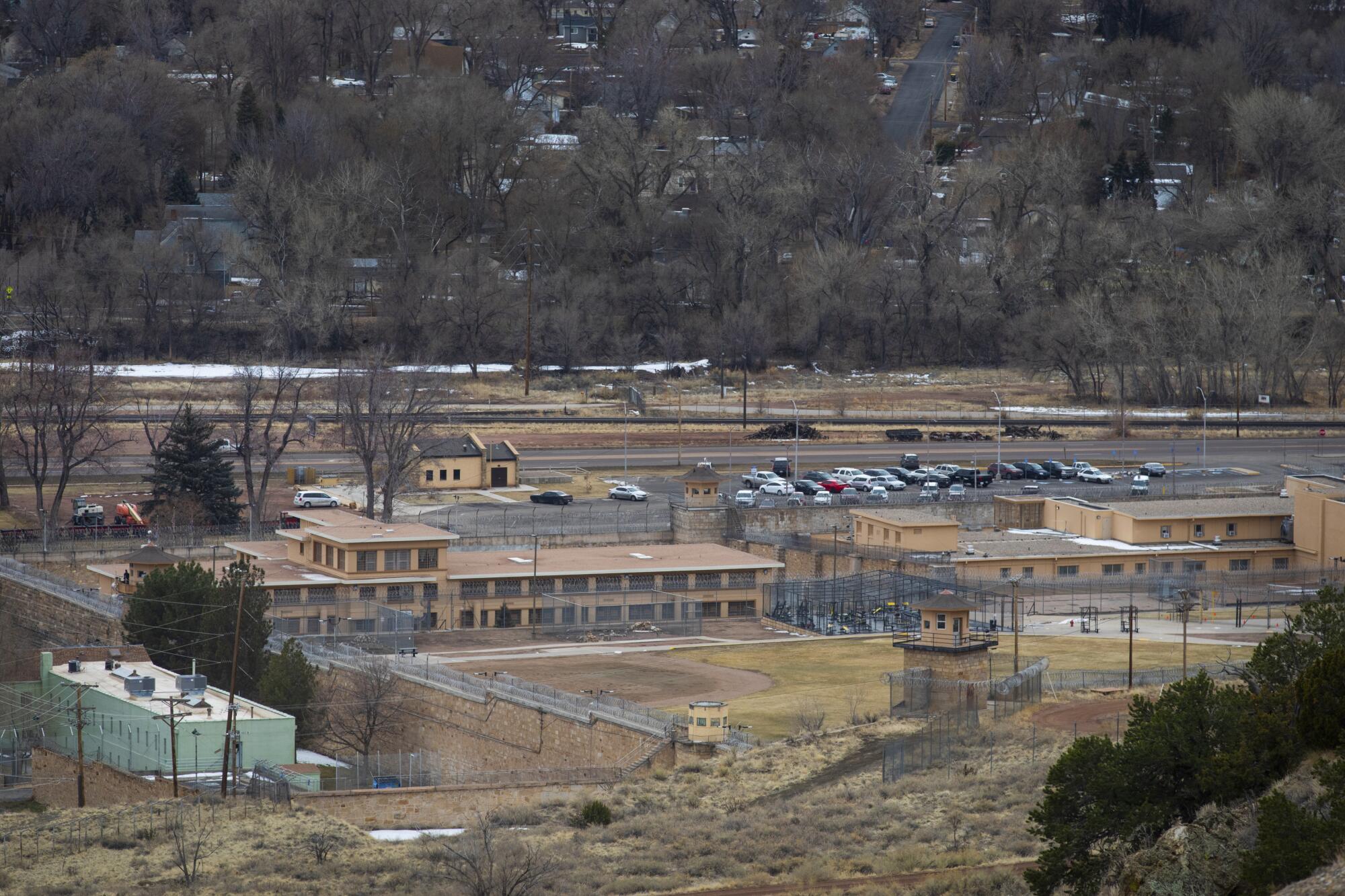

CAÑON CITY, Colo. — Jhil Marquantte lived behind the sandstone walls of the Colorado Territorial Correctional Facility in a 6-by-9-foot cell.

Marquantte, 46, spent years here in this mountain town, but always behind bars — locked inside Territorial, and most of the half-dozen other state prisons that dot this rural stretch of Colorado. If you asked him about home, he’d tell you it was two hours north in Denver where he grew up and his family still resides — and where he long dreamed of returning after serving his sentence.

“My prison cell was not a home,” said Marquantte, who was paroled in 2018 after serving 26 years for murder and returned to the Denver area. “A prison should not be a home for any other person.”

Marquantte’s concern cuts to the core of a long-percolating criminal justice question surrounding the 2020 U.S. census: Should prisoners be counted as residents of the community where they’re incarcerated or of their home when they were arrested and where they generally return to upon release?

With the census officially due to begin Wednesday, the debate has become increasingly timely. After the tally is completed, states will use the numbers to redraw legislative and congressional districts, a once-per-decade procedure with broad implications for whether communities of color have an equitable opportunity at electing candidates who represent their interests and will fight for their concerns. And, in turn, the outcome of redistricting has a ripple effect on what programs — housing, education, healthcare — are funded over the next 10 years.

“Counting people who are incarcerated where they have been imprisoned leads to a big distortion,” said Justin Levitt, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles. “The people incarcerated in a prison facility are often vastly demographically and socioeconomically different from the profile of local residents, with vastly different needs.”

The U.S. Census Bureau counts inmates as residents of the counties where they’re imprisoned — a practice that officials say is meant to provide the most accurate and fair way of capturing a moment-in-time count. Still, in recent years, a wave of states have passed laws requiring post-count adjustments during legislative redistricting to avoid what critics refer to as prison gerrymandering.

Advocates contend that regions where prisons are located — often rural, predominantly white areas — have unfairly inflated their numbers, and thus their political clout, by being able to count inmates such as Marquantte, who is black. Many of the inmates are Latino or black men from more densely populated areas.

It is unjust, advocates say, to count prisoners — who in most states can’t vote while incarcerated and often long beyond — as residents of communities whose demographics and needs so drastically differ from their home communities.

“This siphoning of black urban political power into white, rural communities is the modern-day version of the Three-Fifths Compromise, and violates the principle of one person, one vote,” said Marc Morial, president of the National Urban League, a civil rights group.

April 1 is Census Day. What do you need to know about filling out the 2020 census? What information does the government want, and what ever happened to that citizenship question?

A handful of states, including California, have addressed prison gerrymandering and, in recent weeks, lawmakers in 20 other states, including Illinois and Virginia, have introduced bills to deal with the practice.

New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy recently signed a law requiring that, for redistricting purposes, the state must adjust data in order to count incarcerated people according to their last known address before their imprisonment. In Colorado — where a fierce rural-and-urban divide shapes many policy discussions, including gun control — the Legislature recently passed a similar bill that the governor has signed into law.

The NAACP in February sued Pennsylvania, arguing that the state was “artificially and arbitrarily” inflating the political power of the predominantly white voters in rural counties where some of the state’s largest correctional facilities are located. In turn, the lawsuit contends, the state was diluting the power of black and Latino voters in more urban parts of the state. The suit is pending, as is a similar suit filed by the NAACP in Connecticut two years ago.

In Illinois, where 60% of state inmates are from Chicago or elsewhere in Cook County, 90% are counted as residents of another county, according to the Prison Gerrymandering Project, an extension of the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit that focuses on criminal justice reform.

In Colorado, which, like many other states, disproportionately incarcerates black and Latino men, many of those inmates are imprisoned in either the rural eastern plains or the southern foothills of the Rocky Mountains, such as here in Cañon City.

The state’s legislative districts are divvied up so that each contains roughly 77,000 constituents and, in rural communities with prisons, such as the Cañon City-area, nearly 10% of some districts are made up of prisoners. (Fremont County, where Cañon City is located, is home to roughly a dozen state and federal lockups, housing more than 7,500 inmates — one of the biggest per capita prison populations in the country.)

While the average state prison sentence is about three years, according to corrections data, redistricting shapes political representation for a decade.

State Rep. James Coleman, a Denver Democrat, says he supported the anti-gerrymandering legislation because it only makes sense to count inmates in the communities where they had lived.

“When people get out and they’re voting,” Coleman said, “their district needs fair and accurate representation.”

In New Jersey, then-Republican Gov. Chris Christie vetoed a similar measure in 2017. “Prisoners are consuming services and resources at the prison,” Christie said, in explaining his veto, “and may have only fleeting, dated or tenuous ties to their prior residence.”

As coronavirus spreads, California prisons plan to release 3,500 inmates early.

In Colorado, state Sen. Dennis Hisey, a Republican from the Cañon City area, says he considers prison inmates his constituents.

“They’re a part of rural Colorado,” Hisey said on a recent afternoon while walking the perimeter of Territorial, where silhouettes of guards inside towers overlooking the prison can be seen from the street. “They are essentially residents.”

Hisey views the measure passed by Democrats, who control both chambers of the Colorado Legislature, as little more than “a liberal power grab.”

While the measure doesn’t overtly focus on the allocation of money, Hisey believes funding will inevitably be affected somehow in the years ahead.

“This will dilute the voice of rural Colorado,” he said.

That’s a sensitive subject here.

In 2013, the Colorado Legislature passed background checks and limits on ammunition magazines for guns, a move that some rural Coloradans viewed as an infringement on their 2nd Amendment rights. Some still protest on the steps of the Capitol.

Then came crackdowns on oil and gas drilling, a big source of employment in some rural parts of the state. It started to feel like the cities mattered more than the small towns, Hisey said, and the gerrymandering bill only made things worse.

Cañon City Councilman Brandon Smith owns a barbershop on Main Street from which the towers of Territorial are visible. Many of his clients are prison guards, he said, and inside the shop he has a spot where, after getting a fresh cut, one can take a gimmicky mug shot.

“The way I see it,” he said, “where you sleep a majority of the time is where you live.”

But to Marquantte, that amounts to oversimplification.

“Cañon City was never my home,” he said. “I never attended a political town hall, never knew my representative. My home is the Denver area and it’s where my voice is heard.”

Marquantte, a native of Denver, wound up in prison, sentenced to 60 years, for a shooting that left a man dead in the summer of 1992.

During his high school years , he acknowledged, he fell in with a circle of drug dealers and gang members.

Since his parole two years ago, he has lived in Aurora, a Denver suburb and works full time as a property manager.

On a recent afternoon, Marquantte — who serves on the board of a local recidivism support group — traveled to the state Capitol in Denver to testify in favor of the anti-gerrymandering legislation. He wanted the lawmakers to have a face to put to the issue.

“Inside of a prison the guys have no voice,” he said.

Marquantte said that he often lay in his cell thinking about what he would do with his life once released. He is now proud, he said, of the man he has become.

This was the first time he testified before a legislative committee, he said. And as he sat down before the legislators, he wanted them to know that, when he got out in 2018, he did something he’d never done before: He voted.

Lee reported from Cañon City and Kambhampati from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.