BISBEE, Ariz. — Mike Anderson waded through knee-high weeds as his index finger traced a path along a crinkled map of Evergreen Cemetery.

“They’ve got to be close,” the former newspaperman turned historian muttered.

He walked briskly down a row of headstones, his masked face sweating under the cloudless afternoon sky, until he spotted three slabs of granite whose death dates now echo back to a frightening moment here in southeastern Arizona.

Crane 1918. Henderson 1918. Carlson 1918.

Across several acres, you’ll find that year etched into many headstones — a reminder, Anderson said, of how the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 wiped away entire families and devastated the economy of this copper mining town.

“The community here knows a pandemic and has really experienced one,” he said. “It hasn’t been that long ago.”

As the death toll climbs for the novel coronavirus — Arizona is a hot spot in the U.S. with intensive care unit beds almost at capacity — many people in this small, reinvented town have started to look back 102 years, searching for warning signs and lessons of hope.

The magnitude of infections in this state is alarming, with cases growing over the last three weeks by 150% and eclipsing more than 2,200 deaths. And, like the century-old flu that preceded it, the virus has upended lives even in far-flung outposts like Bisbee (population 5,000), which sits defiantly tucked in a canyon 12 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border.

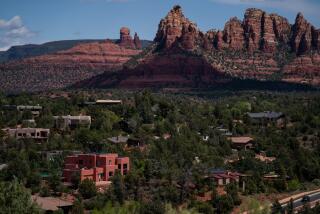

If you ended up here, locals like to say, it was a choice — a haven for immigrants or anyone searching for a new start.

It was easy to settle in and map out a future in Bisbee. But these days, that feels more uncertain, as the town’s main industry — tourism — has slowed dramatically. What happens in the next few months will determine whether many locals stay or go.

“Businesses that have been mainstays for years could be gone by the end of the year,” said Kathy Sowden, who owns an antiques shop near the center of town and expects to see profits decrease 70% this year. “No one truly knows.”

Before the pandemic, people from across the country flocked to Bisbee to drink at the local brewery and stroll Main Street, gawking at the rusting tin roofs of old miners’ homes clinging to the cliffsides. Many tourists descended 1,500 feet into the old Copper Queen Mine, and checked into early-20th-century hotels that all but guaranteed a ghost sighting.

But these days, you’ll find mostly left-leaning locals outside the coffee shop on Main Street having muffled conversations through masks about the virus and a lack of leadership from state and federal officials.

At the Copper Queen Library — one of the oldest in the state, which remained open during floods, fires and Wild West shootouts — a sign near the entrance explaining the current closure reminds people that during the 1918 flu the library shuttered its doors for 76 days.

The library — which has 32,000 books, including ones on the town’s history — has now been closed 99 days and counting.

While Cochise County, where Bisbee is located, has recorded only 22 deaths from COVID-19, the local economy has begun to crater.

There are fewer souls on Main Street, and shopkeepers stand at windows with long, uninterrupted gazes. Business has mostly been dormant since mid-March, except for a brief uptick around Memorial Day, when tourists mostly from Tucson made the 95-mile trek to escape the city during the quarantine.

Cars with Colorado and Texas license plates slowly creep along Main Street, only to soon jump back on Highway 80 north, headed to Tucson.

Although it’s tough to watch tourism dry up, possibly imperiling the town, Anderson said he hoped people took the pandemic seriously. If not, he worries that history — with its unwanted memories, like an old, hidden-away scrapbook — will repeat itself.

“I don’t want this to return to 1918,”Anderson said.

Bisbee was founded in 1880 as a copper town, and both Americans and Mexicans worked in the mines. By the early 20th century, drawn by the promise of riches, Bisbee’s population had swelled to nearly 9,000.

Copper production boomed and mines expanded during World War I; the smaller towns of Warren and Lowell flourished on Bisbee’s outskirts. In the summer of 1917, as miners staged a strike over working conditions at Phelps Dodge, the area’s major mining company, an armed posse of local law enforcement and businessmen rounded up about 1,300 miners and shipped them off on trains to New Mexico. The area was devastated and torn apart by the incident later known as the Bisbee Deportation.

By the next spring, news reports from the Midwest of a deadly flu began to trickle into town. And on Sept. 26, 1918, the influenza officially arrived in Bisbee on the train transporting home the body of Pvt. Carl Axel Carlson, a miner who had been drafted into the Army.

While training at Camp Dix in New Jersey, Carlson contracted the flu and died. Back in Bisbee, he was buried with military honors at Evergreen Cemetery — the first of many headstones planted during the pandemic.

By mid-October, nearly 130 cases were confirmed, and by the end of the year some 160 people had died. In the months that followed, as the flu continued to fester, 20% of the city’s workforce lost their jobs.

A headline in the Bisbee Daily Review screamed: “Influenza Epidemic Effect Will Be Felt in Production of Copper.” After the war, demand for copper fell and mostly continued a downward decline until Phelps Dodge shuttered production at the Copper Queen Mine in 1975.

Mayor David Smith draws parallels between what the flu did and what the virus is doing now. His office estimates that, like copper before it, the town’s tourism trade — which conjures a rustic, mythic charm — could take a 70% hit this year.

“We’re all mom-and-pop stores here,” he said. “Only fast food in Bisbee is a Burger King.”

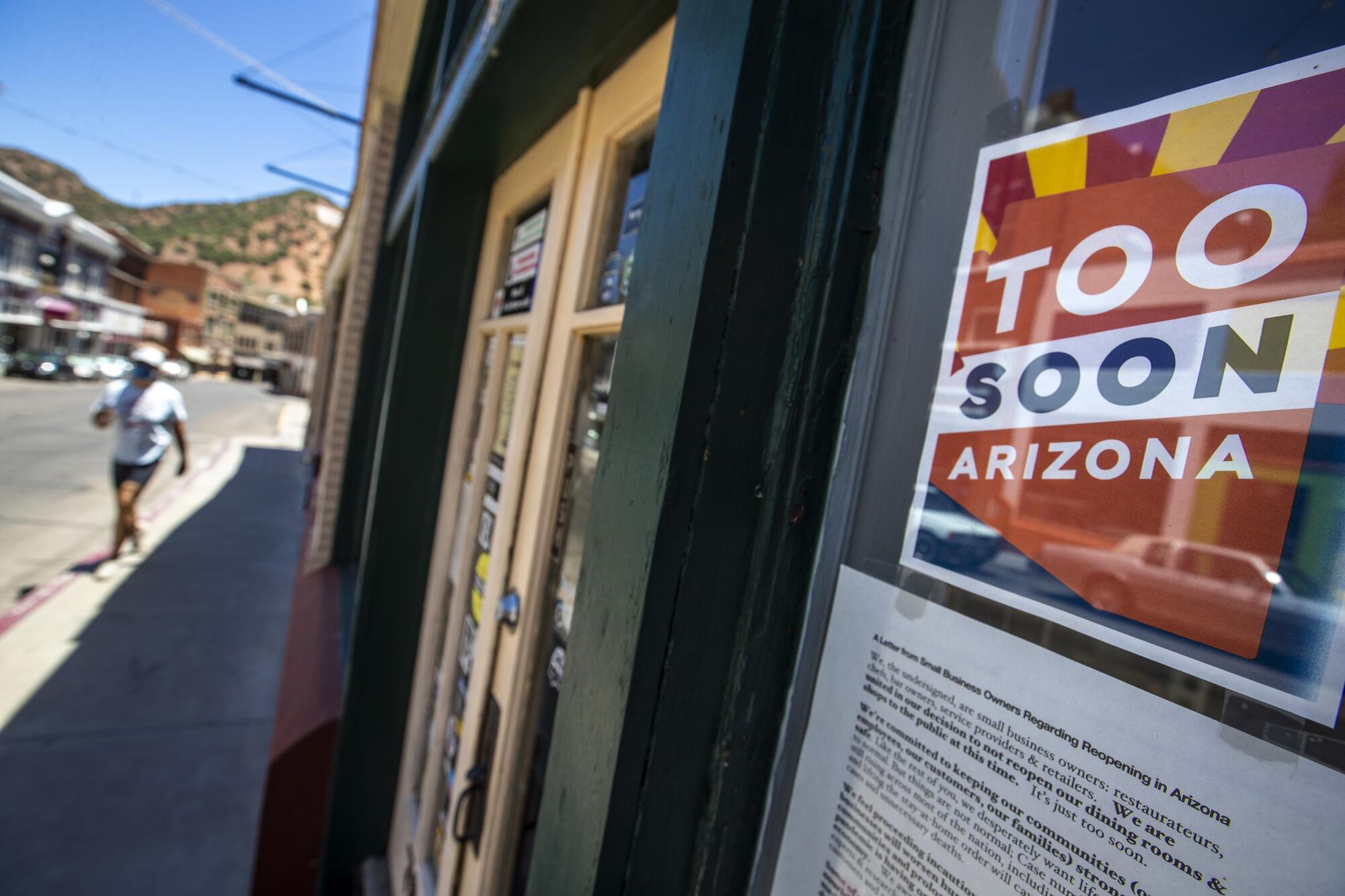

Smith splits his time between his office at City Hall and his kitchen table, providing daily updates to residents through email blasts. He worries about the town’s budget and economy, but even more so about the virus. When Republican Gov. Doug Ducey allowed businesses to reopen in May — a move that fell in line with President Trump’s rush to revive the nation but led to the current surge — Smith was frustrated and upset.

“It was too soon,” he said, “way too soon to open.”

For many here, the coronavirus closures hit at the worst possible time.

The peak tourist season comes between January and April — months with clear nights and 70-degree days, when snowbirds flock to Arizona to escape winter in other parts of the country.

On a recent afternoon, Mel Sowid stood behind the counter of his shop, Mel’s Bisbee Bodega, across Main Street from the library, waiting for customers. His shop was one of the few spots open in town and before long some day-trippers from Tucson dropped in to buy bottled water.

While he usually does well selling Bisbee T-shirts and hats, CBD oil and postcards, lately the main thing keeping him in business are the food snacks he sells. Sowid loves the lore and history here, and he takes pride in seeing his community celebrated as a tourist destination.

But the last few months have been hard.

“We hope to survive,” he says, “but are not sure.”

The bodega has been Sowid’s life for the last five years. He moved to southeastern Arizona from Lebanon in 1980 to study at Cochise College. He met his wife, the daughter of a miner, and he settled into Bisbee. Over the years, family has come to visit and recently, his nephew, Hassan Sowid, moved here on a student visa to study nursing at his alma matter. Now, Hassan works part time in his uncle’s store.

“It’s a dream to become a nurse and work in medicine,” Hassan said as he rang up a pack of cigarettes for a customer. “The coronavirus has made me want to be in medicine even more.”

“Yikes, good luck,” the customer responded.

Mel Sowid recently received a small Paycheck Protection Program loan from the federal government, which he said would cover a few months of rent for his retail space.

“After that,” he said, “who knows?”

A short walk up Main Street from Sowid’s bodega, you’ll spot Finders Keepers, Sowden’s antique shop, with a sign on the door saying it’s temporarily closed. Most years, the store rakes in $250,000, she said. But this year, if lucky, she expects to make about $75,000.

Sowden didn’t qualify for a PPP loan, she said, because she doesn’t have a payroll for the business she co-owns with her partner, Deborah. The couple, who moved here from San Diego, were the first to register for a civil union when Bisbee became the first city in the state to allow civil unions between same-sex couples in 2013.

“The death from the virus is devastating,” she said on a recent morning. “And for many of my neighbors, a way of life, we fear, will be gone for a long time.”

With Arizona continuing to see a steady increase of coronavirus infections, Bisbee is taking precautions like many cities across the nation. A mandatory mask ordinance has been in place since late June, dining-in at restaurants is at less than 50% (per state order), and city buildings are shuttered.

On a recent morning, before the desert sun made the outdoors unbearable, Anderson, the historian, walked through the cemetery on the edge of town. It’s good exercise, and he enjoys studying the old headstones — a history that now somehow doesn’t seem so far off.

Anderson splits his time between studying up on the 1918 flu and co-hosting a public radio show on 96.1 KBRP called “Bisbee Gone Viral,” which among other things is dedicated to coronavirus coverage.

During his walk, he stopped at Carlson’s granite headstone and thought about how he had been the first victim of the 1918 pandemic here.

“None of us want to see what happened in Bisbee then happen now,” he said. “Only time will tell.”

Whitehurst 1918. Villa 1918. Lucouvich 1918.

This is the first in a series of occasional stories on the coronavirus’ effect on the town of Bisbee.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.