Biden’s bind: Dismantling Trump immigration policies without sparking a border rush

- Share via

MEXICO CITY — A day after an SUV packed with migrants crashed in Imperial County last week, leaving 13 dead, police in southern Mexico encountered a disturbing scene: more than 200 U.S.-bound Central Americans, a quarter of them children without adult supervision, crammed inside a tractor trailer.

The two incidents — the fatal collision in California, and the discovery of the migrant-jammed big rig more than 1,000 miles away — dramatize the challenge facing the Biden administration as U.S. officials struggle with a conundrum: How to dismantle Trump-era immigration restrictions, as President Biden has promised to do, without triggering a mass convergence on the Southwest border.

So far, repeated declarations from the White House and elsewhere seeking to discourage would-be migrants have failed to deter a surge of people hopeful that their turn has come.

“There has been an erroneous perception on the part of many migrants that it is going to be easier to enter the United States,” said Alberto Cabezas, spokesman in Mexico for the International Office for Migration, a United Nations agency. “This message is false. The border is closed, there is a pandemic. This is not a moment to go to the border.”

The surge actually began well before Biden’s Jan. 20 inauguration — even before he was elected president in November. U.S. Customs and Border Protection says authorities detained or turned away almost 300,000 foreign nationals at the Southwest border between October 2020 and January 2021, a 79% increase compared with the same period in 2019-20.

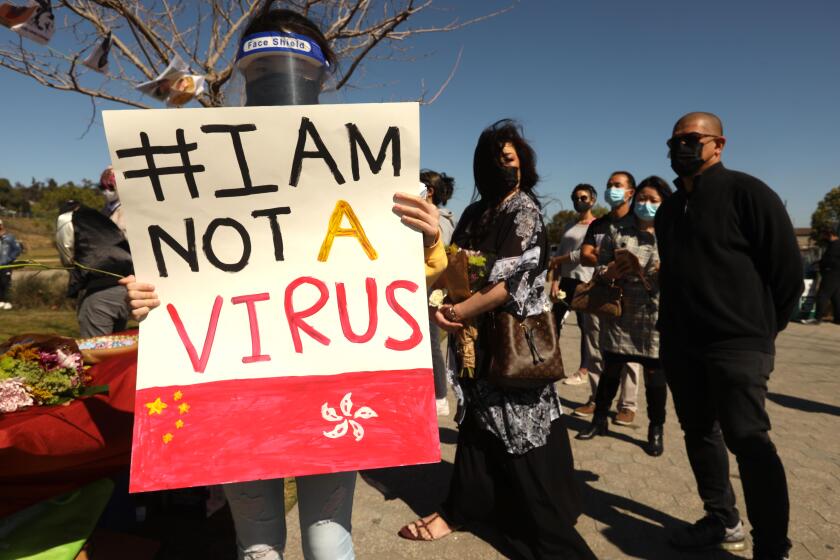

Hate crimes against Asians and Asian Americans jumped dramatically in major U.S. cities in 2020.

Here in Mexico, anecdotal accounts suggest that many more are now en route, expecting a warmer reception than President Trump’s cold shoulder. Shelters along migrant routes are overbooked. Vehicles packed with smuggled migrants are streaming northbound on highways and back roads, according to Mexican officials.

“We’ve seen a big increase in the arrival of migrants, especially in February,” said José Fernández, who helps run a shelter in Veracruz state, a key migrant corridor. “The rumor is everywhere that the United States is going to let them enter. There’s a lot of optimism.”

A new cohort of asylum seekers and others has been streaming into Mexico’s northern border towns, already bursting with tens of thousands seeking U.S. entry.

“The trip here was very difficult, but we have faith that the government of the United States will give us an opportunity,” said César Moscada, 38, a Honduran national who had arrived five days earlier with his wife, son, 17, and daughter, 8, to the border city of Matamoros, across the Rio Grande from Texas. “We’ve heard that [Biden] won’t separate families, that he is going to help migrants.”

The underlying factors pushing immigration — principally poverty and violence — haven’t gotten any better in Central America and Mexico in the past year. The pandemic has battered already moribund economies. A pair of hurricanes last year dispossessed tens of thousands. The region also remains among the world’s most crime-ridden terrain, fertile turf for a sinister assemblage of international cartels, extortion rings and kidnap gangs.

An assessment that crossing the border now may be easier than during the height of the Trump administration is not completely off base, especially if children are making the attempt.

While the Biden administration has maintained Trump’s controversial pandemic health order allowing rapid expulsion back to Mexico of illicit border crossers, it has loosened restrictions on children, and more families have been allowed to proceed into the United States after making claims for asylum and receiving court dates. That shift has registered with both migrants and the smugglers who closely monitor the tactile reverberations of even slight alterations in U.S. border policy, analysts note.

“There’s this belief that if you try to cross with minor children it’s going to be easier,” noted Cabezas. “The human traffickers tell them that.”

Many northbound migrants are turning to smugglers, known as coyotes, or polleros, after the slang word pollos (chickens) used for migrants, to help them navigate an often-hazardous land journey that can stretch 1,000 miles or more. Mexicans and others have long employed coyotes to enter the United States illegally. Ten of the 13 who died in the Imperial County crash — which involved an apparent smuggling vehicle — were Mexican citizens.

An ongoing enforcement crackdown in Mexico and Central America has also meant a greater reliance on smugglers within Mexico. Facing strong-arm tariff threats from Trump, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador dropped his initial welcome mat policies for migrants and moved to stop them. Mexico has posted military and police along major trafficking corridors, thrown up checkpoints and deployed patrols conducting raids on migrant safe houses. Police and soldiers have broken up large-scale migrant caravans.

In addition, Mexican authorities have been issuing fewer of the visas that once allowed many non-Mexicans to reach the northern border relatively hassle free.

“If the migrants aren’t receiving these documents that used to make it easier to travel, then they have to risk it and contract with these polleros, who are now making a big business,” said Father Alejandro Solalinde, a Mexican priest who runs a shelter in southern Oaxaca state. “What the Mexican bureaucracy is doing is sending these migrants into battle without rifles.”

People smuggling is a lucrative trade. Smugglers may earn anywhere from $2,000 to more than $12,000 per person moved, depending on the distance and other factors. Relatives in the United States typically help migrants pay the fee.

In recent weeks, Mexican authorities have regularly intercepted smugglers’ vehicles filled with migrants. Mexican police have also found many migrants abandoned by smugglers.

The most infamous incident was the discovery in January of the bodies of 19 gunshot victims — their bodies burned — in a truck in the state of Tamaulipas, which shares a long border with Texas. Most were Guatemalans. Authorities have charged Mexican state police officers in the slayings. The motive remains unclear.

The scores of migrants found locked inside a tractor-trailer Wednesday near a toll booth in the southern state of Chiapas were all alive, though police say smugglers gave them no food or water.

Of the 201 crammed into the trailer, Mexican authorities said, 51 were unaccompanied minors; another 78 were children traveling with guardians. The rest were adults traveling without families. All were expected to be deported back to homelands in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. The driver was arrested on suspicion of trafficking.

U.S. authorities also suspect smuggling in the fatal crash a day earlier in Imperial Country. The migrant-packed Ford Expedition ferrying more than two dozen people had entered U.S. territory through a hole cut out of the border fence near Calexico, officials say.

Such crashes are not uncommon. Smuggling vehicles are typically overcrowded — maximizing profits — and tend to prowl back roads to avoid detection. In one notorious case, 23 Guatemalans headed to the United States perished in 2019 when a truck packed with human cargo veered off an isolated thoroughfare in southern Mexico.

“Unfortunately, many migrants are now traveling with polleros who transport them in lamentable conditions,” said Fernández of the shelter in Veracruz. “They rob their money and stack entire families, with children, on top of one another.”

Still, the people come, many now with a renewed sense of expectations as U.S. border policies are once again evolving, and Trump has migrated south to his Florida resort.

“You don’t flee your country with the idea that it’s easy, that it’s fun,” said Moscada, who said he abandoned the barbershop business in Honduras after receiving death threats. “But we have the hope that authorities in the United States will listen to us, that they recognize we escaped to save our lives. That’s the hope that we have.”

Special correspondents Cecilia Sánchez and Liliana Nieto del Río in Mexico City and Juan José Ramírez in Matamoros contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.