Here’s the latest on the Violence Against Women Act, which is up for reauthorization by Congress

- Share via

In the eyes of proponents, reauthorizing the federal Violence Against Women Act should be a no-brainer.

Since it was implemented in 1994, the act has resulted in billions of dollars for tribal, state and local governments, as well as nonprofit organizations, working to help victims and prevent domestic violence, sexual assault and stalking throughout the United States. Nevertheless, hundreds of organizations that provide services such as emergency shelter, legal aid and mental health therapy keep straining to meet demand.

Through the act, Congress typically eases some of the financial strain by appropriating hundreds of millions of dollars — about $550 million annually — for the various programs, but expanding protections requires legislators to reauthorize VAWA.

In recent years, the act has been rejected by some lawmakers, lobbyists and others who oppose recognizing the rights of transgender people and object to keeping guns from those who’ve been convicted of abusing someone they dated. Prison abolitionists argue that the act places a premium on putting offenders behind bars, instead of providing rehabilitation.

The latest version of the measure, introduced in early March, was approved by the U.S. House of Representatives. The Senate is expected to vote on its reauthorization this year, though a date has not been set.

Here’s some information about the act, as well as how to help someone who might be in danger:

Why aren’t Republicans supporting renewal of the Violence Against Women Act? It may have something to do with gun ownership.

What’s in the latest version of the act?

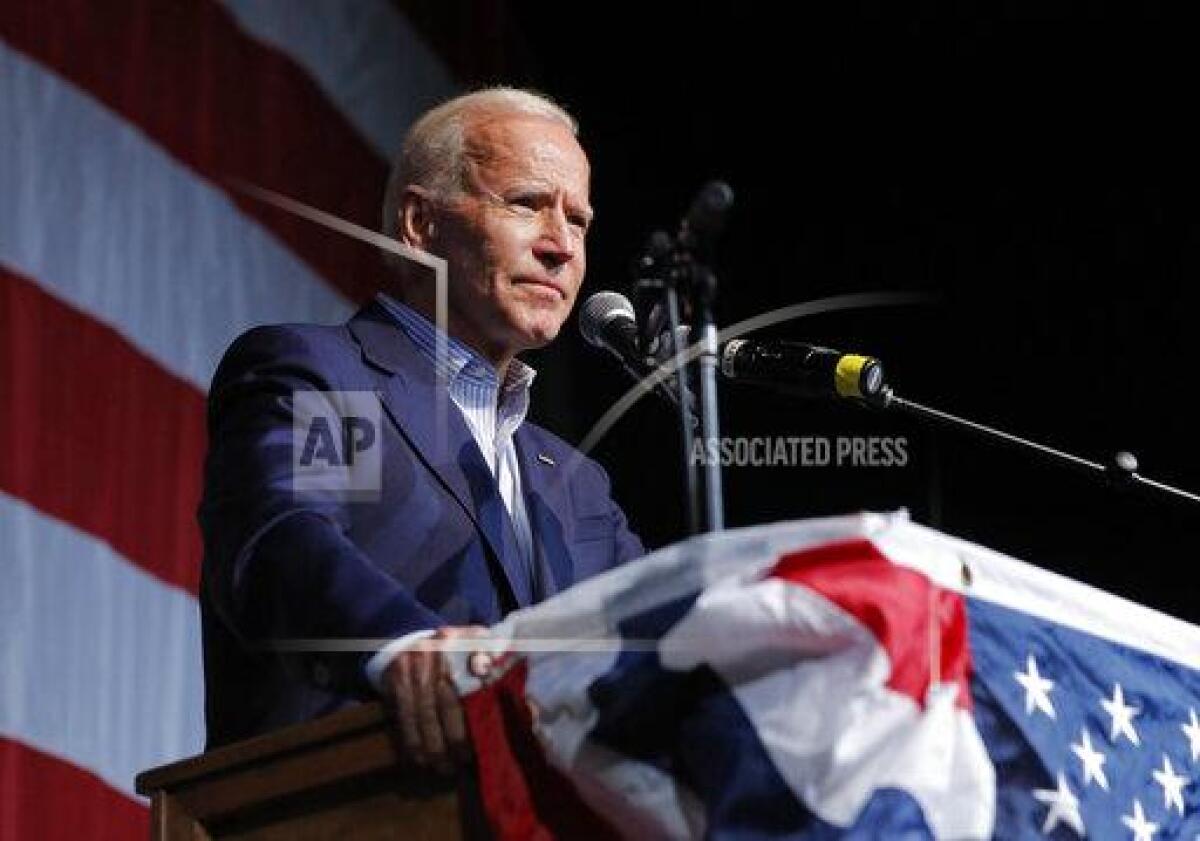

The Violence Against Women Act Reauthorization Act of 2021 builds on landmark legislation in 1994, which was enacted under the leadership of then-Senate Judiciary Chair Joe Biden. The original Violence Against Women Act was the first to acknowledge domestic violence and sexual assault as federal crimes — regardless of whether the acts were committed by strangers, relatives or spouses.

The latest iteration of VAWA is a wide-reaching bipartisan measure that maintains established enforcement provisions, such as enhanced sentencing of repeat federal sex offenders, and guarantees protections for all victims, irrespective of their gender.

According to advocates, some victims hesitate to seek help for reasons such as language barriers or concerns about engaging with law enforcement. The VAWA reauthorization act includes proposed funding for culturally specific services.

Because advocacy groups such as Safe Housing Partnerships have found that domestic violence is a top driver of homelessness for women, the VAWA reauthorization would enable victims in federally assisted housing to get relocation vouchers, keep their housing after a perpetrator leaves or terminate a lease early.

Each time VAWA is up for reauthorization, “We ask ourselves: What do we now know that’s different? What survivors don’t have access to safety and justice?” said Monica McLaughlin, director of public policy at the National Network to End Domestic Violence.

McLaughlin said housing protection for victims was included in VAWA in 2005. “Now, in 2021, we’re working to ensure that survivors who live in public or assisted housing have options,” she said.

The latest version of the act also aims to improve accountability. Noting that the Department of Justice found that Indigenous women on some reservations are slain at more than 10 times the national average, the VAWA reauthorization reaffirms Tribal Nations’ authority to prosecute non-Indigenous offenders who commit crimes on tribal territory.

The reauthorization act also seeks to close the “boyfriend loophole.” Currently, federal law prohibits people who’ve been convicted of domestic violence from owning or purchasing firearms. However, this applies only to those who have been married to, lived with or have a child with the victim. The 2021 version of the act expands the prohibition to current and former dating partners, as well as those convicted of misdemeanor stalking.

Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-Mich.), who drafted the provision and pressed for it to be included in the reauthorization act, says it’s an urgent matter of life and death.

She and other lawmakers who favor keeping guns from violent dating partners cite the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, which signals that when an abusive partner has access to a gun, a domestic violence victim is five times more likely to be killed.

They also point to a 2018 study published in Preventive Medicine, an international journal on public health policy, which found that more than 4 in 5 domestic violence incidents reported to the police involve partners who are dating, not married.

“I’m not trying to take guns away from most people,” said Dingell, whose late husband was a National Rifle Assn. board member. “But if someone’s demonstrated that they could abuse somebody, then we need to do something to prevent violence.”

The VAWA update also includes provisions for women in prison. When deciding whether to assign a transgender or intersex person to a male or female facility, the Bureau of Prisons would have to consider whether a placement would ensure the prisoner’s health and safety and take the prisoner’s own views into account.

To more effectively address sexual violence on college campuses, personnel would receive training on how to conduct interviews without judging or blaming victims for alleged crimes. When possible, they would also provide victims with a recording of the interview.

To stop violence from happening in the first place, the new plan calls for increased investment in ongoing prevention education, encompassing themes ranging from dating violence to reproductive coercion, essentially attempts by male partners to promote pregnancy.

The Democratic-led House passed two measures, one addressing domestic violence, the other removing the deadline to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment.

What’s supposed to happen next?

Both houses of Congress must agree on the same version of the measure before it goes to the president. The 50-member Democratic caucus in the Senate needs 10 Republican votes to reach the 60-vote threshold required to pass the reauthorization. If they fail to work out a compromise, VAWA could get blocked.

If they work out a deal, President Biden — who called VAWA his “proudest legislative accomplishment” and pledged to make its reauthorization one of his first 100 days priorities while on the campaign trail — will likely be prepared to sign it.

Where can people find help?

If you or someone you know is in immediate danger, please call 911.

If you or someone you know is experiencing violence at home or in any relationship, you may call the National Domestic Violence Hotline anytime at (800) 799-7233. If you prefer not to speak on the phone, you can also chat online at TheHotline.org. This hotline provides free, confidential support, including safety plans and help accessing healthcare services in more than 200 languages.

If you are someone seeking to change your abusive behavior, you may call the same violence hotline number. You can also click here for more information.

If you or someone you know has experienced sexual violence in any context, you can get immediate support by calling the National Sexual Assault Hotline at (800) 656-4673. This hotline provides a number of resources, including guidance before receiving medical attention, help navigating the criminal justice system and support with accessing mental health services.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.