U.S. transfers Guantanamo detainee to home country in a shift from Trump-era policy

- Share via

WASHINGTON — In a major policy shift from that of the Trump presidency, the Biden administration on Monday transferred a Guantanamo Bay detainee back to his home country for the first time, years after he was recommended for discharge.

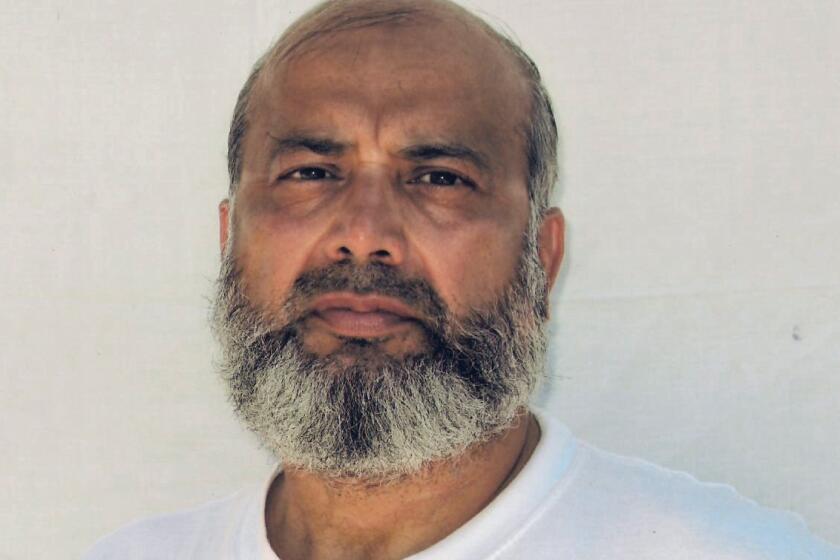

The prisoner, Abdullatif Nasser, who is in his mid-50s, was cleared for repatriation to Morocco by a review board in July 2016 but remained at Guantanamo for the duration of the Trump presidency.

A review board determined that Nasser’s detention was no longer necessary to protect U.S. national security, the Pentagon said Monday. The board had recommended authorization for Nasser’s repatriation, but that couldn’t be completed before the end of the Obama administration, it said.

Nasser, also known as Abdul Latif Nasser, arrived Monday in Morocco, where police took him into custody and said they would investigate him on suspicion of committing terrorist acts — even though he was never charged while in Guantanamo.

The State Department said in a statement that the Biden administration would continue “a deliberate and thorough process focused on responsibly reducing the detainee population of the Guantanamo facility while also safeguarding the security of the United States and its allies.” A senior administration official who insisted on anonymity to discuss internal deliberations told reporters Monday that the Biden administration is engaged in that process with the ultimate aim of closing the Guantanamo Bay facility.

Of the 39 detainees remaining at Guantanamo, 10 are eligible to be transferred out, 17 are eligible to go through the review process for possible transfer, another 10 are involved in the military commission process used to prosecute detainees and two have been convicted, another senior administration official said.

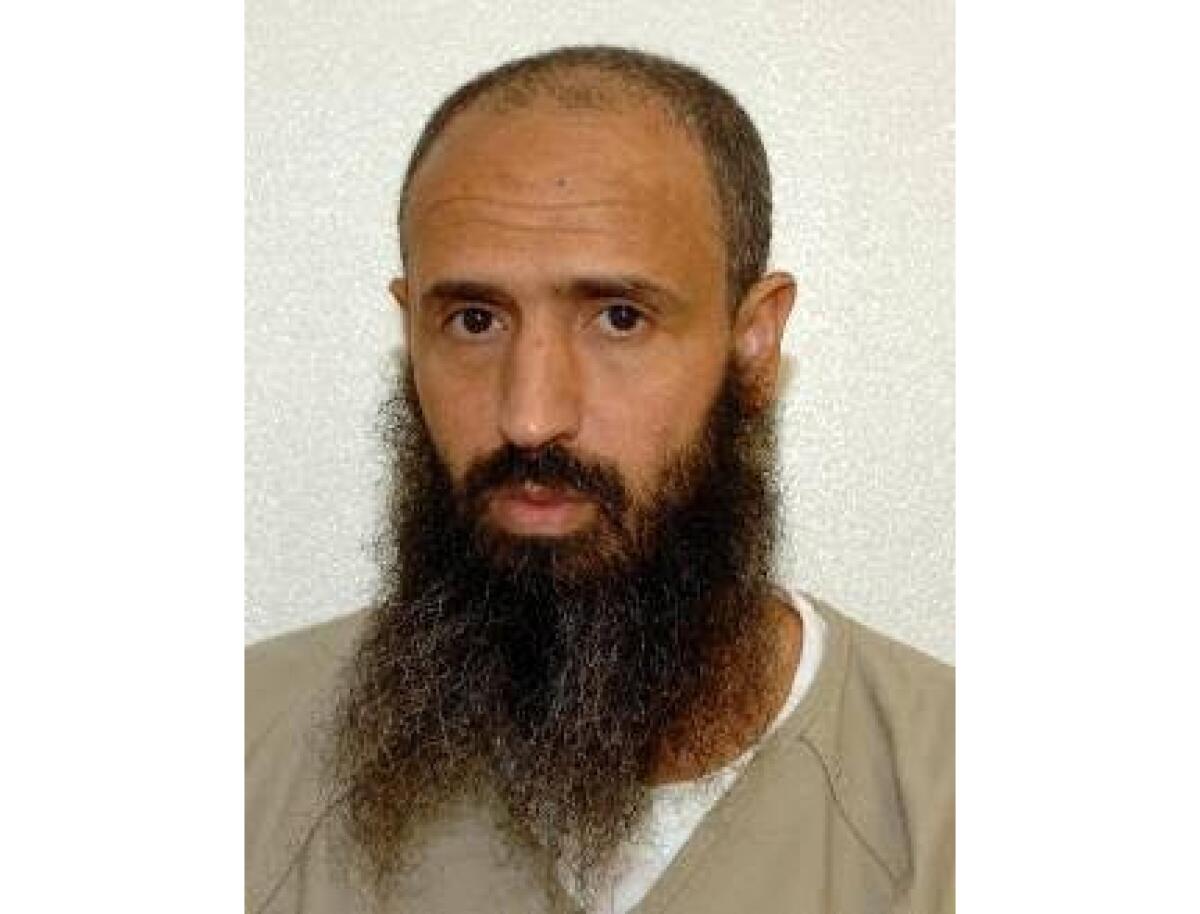

A lawyer says the U.S. has approved the release of 73-year-old Saifullah Paracha, who has been held at the U.S. base in Guantanamo Bay for 16 years.

The administration didn’t address how it would handle the ongoing effort to prosecute five men held at Guantanamo for the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

The detention center opened in 2002. President George W. Bush’s administration transformed what had been a sleepy Navy outpost on Cuba’s southeastern tip into a place to interrogate and imprison people suspected of links to Al Qaeda and the Taliban after the Sept. 11 attacks.

The Obama administration, seeking to allay concerns that some of those released had “returned to the fight,” set up a process to ensure that those repatriated or resettled in third countries no longer posed a threat. It also planned to try some of the men in federal court.

But his effort to close the detention center was thwarted when Congress barred the transfer of prisoners from Guantanamo to the U.S., including for prosecution or medical care. President Obama ultimately released 197 prisoners.

Apparently, the Justice Department has no opinion on whether due process applies to the Guantanamo detainees.

The prisoner transfer process had stalled under President Trump. He said even before taking office there should be no further releases from “Gitmo,” as Guantanamo Bay is often called. “These are extremely dangerous people and should not be allowed back onto the battlefield,” he said.

The possibility that former Guantanamo prisoners would resume hostile activities has long been a concern that has played into the debate over releases. The office of the director of national intelligence said in a 2016 report that about 17% of the 728 detainees who had been released were “confirmed” as having reengaged in such activities, and 12% were “suspected” of doing so.

But the vast majority of those reengagements occurred with former prisoners who did not go through the security review that was set up under Obama. A task force that included agencies such as the Defense Department and the CIA analyzed who was held at Guantanamo and determined who could be released and who should continue in detention.

The U.S. thanked Morocco for facilitating Nasser’s transfer back home.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“The United States commends the Kingdom of Morocco for its longtime partnership in securing both countries’ national security interests,” the Pentagon statement said. “The United States is also extremely grateful for the kingdom’s willingness to support ongoing U.S. efforts to close the Guantanamo Bay Detention Facility.”

In a statement, the public prosecutor at the Court of Appeal in Rabat, the Moroccan capital, said the National Division of the Judicial Police in Casablanca had been instructed to open an investigation into Nasser “on suspicion of committing terrorist acts.” It didn’t specify what those alleged acts were.

Nasser’s attorney in Morocco, Khalil Idrissi, said judicial authorities should not “take measures that prolong his torment and suffering, especially since he lived through the hell of Guantanamo.” Idrissi said he hoped the investigation into Nasser would not “continue to deprive him of his freedom.”

He said the years Nasser spent in Guantanamo “were unjustified and outside the law, and what he suffered remains a stain of disgrace on the forehead of the American system.”

Tahar Rahim, Jodie Foster, Shailene Woodley and Benedict Cumberbatch star in Kevin Macdonald’s well-acted but miscalculated post-9/11 legal thriller.

Nasser initially was told he was going to be released in the summer of 2016, when one of his lawyers called him at the detention center and said the U.S. had decided he no longer posed a threat and could go home. He thought he would return to Morocco soon. “I’ve been here 14 years,” he said at the time. “A few months more is nothing.”

Nasser’s journey to the Cuban prison was a long one. He was a member of a nonviolent but illegal Moroccan Sufi Islam group in the 1980s, according to his Pentagon file. In 1996, he was recruited to fight in Chechnya but ended up in Afghanistan, where he trained at an Al Qaeda camp. He was captured after fighting U.S. forces there and sent to Guantanamo in May 2002.

An unidentified military official appointed to represent him before the review board said he studied math, computer science and English at Guantanamo, creating a 2,000-word Arabic-English dictionary. The official told the board that Nasser “deeply regrets his actions of the past” and expressed confidence he would reintegrate into society.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.