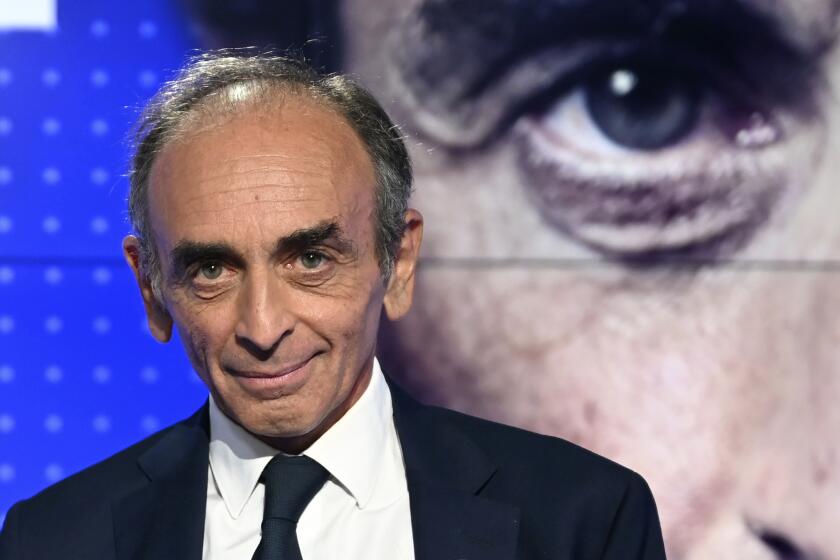

Far-right French candidate turns a racist, taboo phrase into his mantra

- Share via

PARIS — Two words — taboo for many in France because they evoke a conspiracy theory embraced by white supremacists — have been haunting the French presidential campaign.

“Great replacement” rolls off the tongue of far-right presidential candidate Eric Zemmour, who has unashamedly made the phrase the core of his campaign. It’s the false claim that the native populations of France and other Western countries are being overrun by nonwhite immigrants — notably Muslims — who are purportedly supplanting, and will one day erase, Christian civilization and its values.

But when conservative presidential candidate Valerie Pecresse used the same phrase at her first major rally last weekend, politicians and pundits cried foul, saying she had crossed a red line.

Critics said Pecresse, as a mainstream political figure in a way that Zemmour is not, was normalizing a dangerous falsehood that immigration figures in France do not support. The claim of “replacement,” popularized by a French author, has inspired deadly attacks in recent years from New Zealand to El Paso.

Pecresse later denied she was venturing into Zemmour’s far-right territory, contending that her brief remark was misconstrued. Still, the dispute focused attention on Zemmour’s campaign mantra and underscored the threat he represents to mainstream conservatives.

“If I’m a candidate in the presidential election, it is firstly and above all to stop the ‘great replacement’ and to fight immigration,” Zemmour — whose upstart party is named Reconquest — told France 2 TV.

A rabble-rousing TV pundit and author with repeated convictions for hate speech is rocking the early stages of France’s coming presidential election.

Numerous polls place Zemmour fourth among a bevy of candidates for France’s April 10 presidential vote, behind poll leader President Emmanuel Macron — who has yet to formally declare his candidacy — and slightly behind far-right candidate Marine Le Pen and Pecresse. A presidential runoff will be held among the top two candidates April 24 if no one wins outright.

Zemmour, 63, a controversial talk show pundit before entering the presidential race, has been convicted multiple times of inciting racist or religious hatred.

He has, for instance, drawn ire for falsely stating that Marshal Philippe Petain, who led France’s collaborationist World War II Vichy government, saved Jews from deportation to Nazi death camps. Under Petain’s leadership, about 76,000 French Jews were sent to camps; very few survived.

The “great replacement” theory was formulated in 2011 by writer Renaud Camus. But the notion dates to writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, according to Jean-Yves Camus, a French expert on the far right who is not related to the writer.

At the makeshift camps in France near Calais and Dunkirk, migrants are digging in, waiting for their chance to make a dash across the English Channel.

Both Renaud Camus and Zemmour base their unfounded claims that Muslims are already supplanting native French on visual indicators such as Islamic head scarves. Yet less than 10% of France’s population is Muslim.

“Every day when I go to work, I say, ‘Hey, this is France,’” said Jean-Yves Camus. “When Zemmour goes out from his flat ... he says, ‘Wow, this is not France anymore.’”

Polls suggest that between Le Pen and Zemmour, the far right has gained traction in France since the 2017 presidential race, when the centrist Macron beat Le Pen in a landslide in the presidential runoff. Together, the two far-right candidates represent 30% of potential French voters, the polls show, compared with up to 25% for Macron.

One reason for the ground gained by far-right ideology is France’s “difficulty adjusting to a multicultural society,” Jean-Yves Camus said.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In France, where assimilation is the watchword and officials are banned from counting people by origin, “we are supposed to be equal but only if we are identical,” he said.

“There is certainly some kind of mainstreaming of many issues that were only fringe topics, let’s say 10 or 15 years ago,” Jean-Yves Camus said. “It’s not only about the great replacement. ... [It’s] anything that has to do with immigration and French identity and the roots of the French nation.”

He also cites an amorphous fear of Muslims, viewed by some as “the enemy within” because of several terrorist attacks carried out by Muslim French citizens. That is devastating for the nation’s Muslim population, estimated at 5 million, which is overwhelmingly peaceful but often unfairly stigmatized.

The rector of Paris’ Grand Mosque urged Muslim citizens to vote, asking them to “sanction the apostles of racism and those who look down on French of the Muslim faith.”

French President Emmanuel Macron has provoked protests by using a vulgarity to describe his strategy for pressuring holdouts to get COVID-19 shots.

Without naming names, rector Chems-Eddine Hafiz denounced the far right in a commentary in the newspaper Le Monde, saying the movement’s “extremist speech” must be disavowed just as Islamist extremists are.

Le Pen, once best known for her anti-immigration portrayals of a France with minarets dotting the countryside where church steeples once stood, has softened her image to broaden her voter base. She has not uttered the controversial words that are Zemmour’s mantra. Several figures in her far-right National Rally party have complained, saying that Le Pen has gone off-message, and have defected to Zemmour’s camp.

Zemmour’s latest far-right achievement was a phone conversation Monday evening with former President Trump. Zemmour, who reportedly requested the chat, told reporters that the two discussed the “destiny and perspectives” of the U.S. and France, which he claimed are both “in the torment of a war of civilizations.”

Le Pen was philosophical. She had hoped, but failed, to meet with Trump during her 2017 campaign.

“I hope that Donald Trump is doing well,” she told reporters in Villers-Cotterets, where she was promoting the French language against an Anglo-Saxon “invasion.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.