Russia may be on the verge of a debt default. Here’s what that would mean

- Share via

Ratings agencies say Russia is on the verge of defaulting on government bonds after its invasion of Ukraine, with billions of dollars owed to foreigners. That prospect recalls memories of a 1998 default by Moscow that helped fuel financial disruption worldwide.

The possibility has become more than market speculation after the head of the International Monetary Fund, Kristalina Georgieva, conceded that a Russian default is no longer an “improbable event.”

A look at possible consequences from a Russian default:

Why are people saying Russia is likely to default?

On Wednesday, Russia faces an interest payment of $117 million on two bonds denominated in dollars. Western sanctions over the war in Ukraine have placed severe restrictions on banks and their financial transactions with Russia. Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov has said the government has issued instructions to pay the coupons in dollars, but added that if banks are unable to do that because of sanctions, the payment would be made in rubles. There’s a 30-day grace period before Russia would be officially in default.

So, Russia has the money to pay but says it can’t because of sanctions that have restricted banks and frozen much of its foreign currency reserves. Ratings agencies have downgraded Russia’s credit rating to below investment grade, or “junk.” Fitch rates Russia “C,” meaning, in Fitch’s view, that “a sovereign default is imminent.”

What does the fine print say?

Some of Russia’s bonds allow payment in rubles under certain circumstances. But these bonds don’t. And indications are that the ruble amount would be determined by the current exchange rate, which has plunged, meaning investors would get a lot less money.

A sanctions regime aimed at putting pressure on Russia’s wealthiest citizens has put a spotlight on the global mega-yacht trade.

Even for bonds that allow ruble payments, things could be complicated.

“Rubles obviously aren’t worthless, but they’re depreciating rapidly,” said Clay Lowery, executive vice president at the Institute of International Finance, an association of financial institutions. “My guess is it could be a legal issue: Are these extraordinary circumstance, or were they brought on by the Russian government itself because the Russian government invaded Ukraine? That could be fought out in court.”

Ratings agency Moody’s says that “all else being equal,” payment in rubles on bonds that don’t permit it would be “a default under our definition.” But the agency added that “we would need to understand the facts and circumstances of particular transactions before making a default determination.”

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky will address the U.S. House and Senate on Wednesday morning in a virtual session. What will he ask for?

How much does Russia owe?

Russia as a whole has about $491 billion in foreign debts, with $80 billion due in the next 12 months, according to Algebris Investments. Of that, $20.5 billion is in dollar-denominated bonds held by nonresidents.

How do you know if a country is in default?

Ratings agencies can lower the rating to default, or a court can decide the issue. Bondholders who have credit default swaps — derivatives that act as insurance policies against default — can ask a “determinations committee” of financial firm representatives to decide whether the debtor’s failure to pay should trigger a payout of the swap, which still doesn’t count as a formal declaration of default.

It can be complex. “There will be a lot of lawyers involved,” Lowery said.

What would be the impact of a Russian default?

Investment analysts are cautiously reckoning that a Russia default would not have the kind of impact on global financial markets and institutions that Moscow’s 1998 default did. Back then, Russia’s default on ruble bonds came on top of a financial crisis in Asia. The U.S. government had to step in and get banks to bail out Long-Term Capital Management, a large U.S. hedge fund whose collapse, it was feared, could have threatened the stability of the wider financial and banking system.

Residents trying to leave Sumy and Mariupol are part of the exodus from Ukraine. But will sanctions stop Putin? Poland stuns U.S. with plane offer.

This time, however, “it’s hard to say ahead of time 100%, because every sovereign default is different and the global effects would only be seen once it has happened,” said Daniel Lenz, head of euro rates strategy at DZ Bank in Frankfurt, Germany. “That said, a Russian default would no longer be any great surprise for the market as a whole.

“If there were going to be big shock waves, you would see that already. That doesn’t mean that there won’t be significant problems in smaller sectors.”

The effect outside Russia could be lessened because foreign investors and companies have reduced or avoided dealings there since a round of sanctions imposed in 2014 by the U.S. and the European Union in response to Russia’s unrecognized annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula. IMF head Georgieva said that, although the war has devastating consequences in terms of human suffering and wide-ranging economic effects in terms of higher energy and food prices, a default by itself would be “definitely not systemically relevant” in terms of risks for banks around the world.

Holders of the bonds — for instance, funds that invest in emerging market bonds — could take serious losses. Moody’s current rating implies that creditors would experience losses of 35% to 65% on their investment if there’s a default.

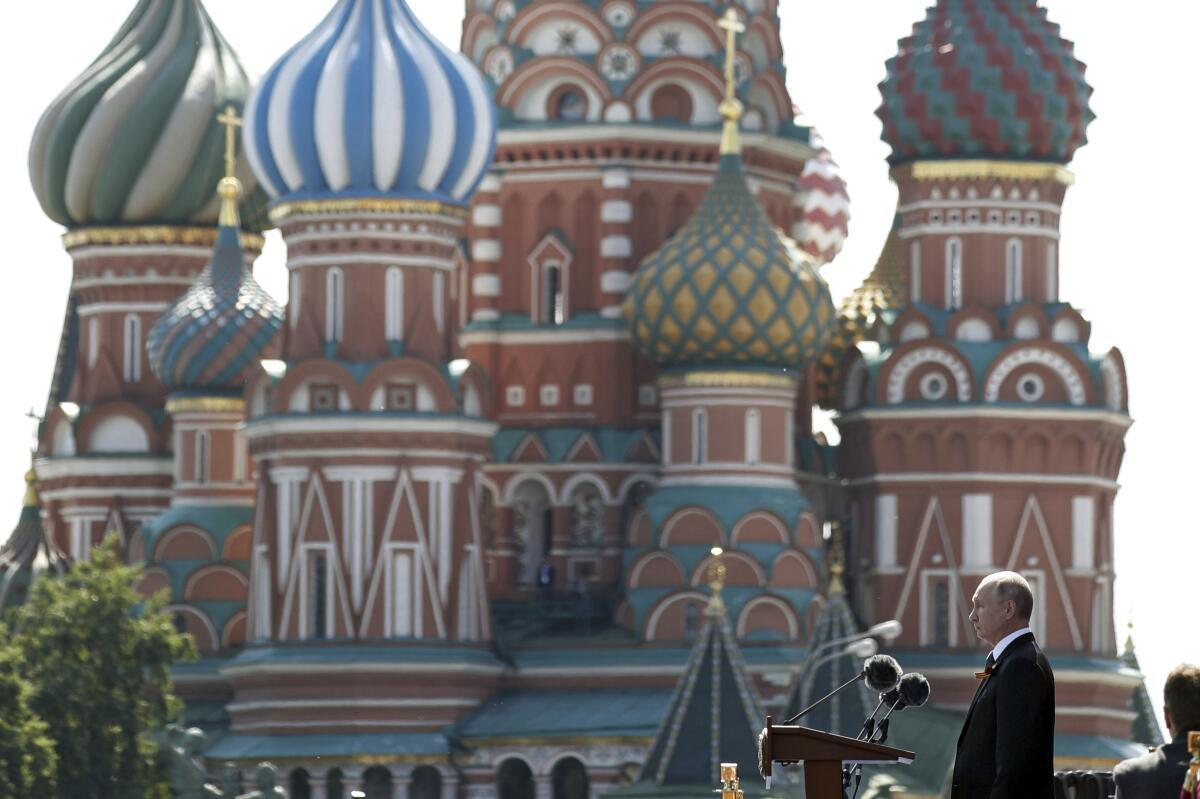

As the war in Ukraine rages, ordinary Russians face a degree of international isolation not seen in decades. What will Putin do next?

What happens when a country defaults?

Often investors and the defaulting government will negotiate a settlement in which bondholders are given new bonds that are worth less but at least give them some partial compensation. It’s hard, however, to see how that could be the case now with the war going on and Western sanctions barring many dealings with Russia, its banks and companies.

In some cases, creditors can sue. In this case, Russian bonds are believed to come with clauses that permit a majority of creditors to agree to a settlement and then force that settlement on the minority, forestalling lawsuits. Again, it’s unclear how that would work when many law firms are now leery of dealing with Russia.

Once a country defaults, it can be cut off from bond market borrowing until the default is sorted out and investors regain confidence in the government’s ability and willingness to pay. Russia’s government can still borrow rubles at home, where it mostly relies on Russian banks to buy its bonds.

Russia is already suffering severe economic impacts from the sanctions, which have sent the ruble plunging and disrupted trade and financial ties with the rest of the world.

So the default would be one more result of Moscow’s political and financial isolation after its invasion of Ukraine.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.