A Buddhist-inspired climate activist’s self-immolation stirs questions on faith and protest

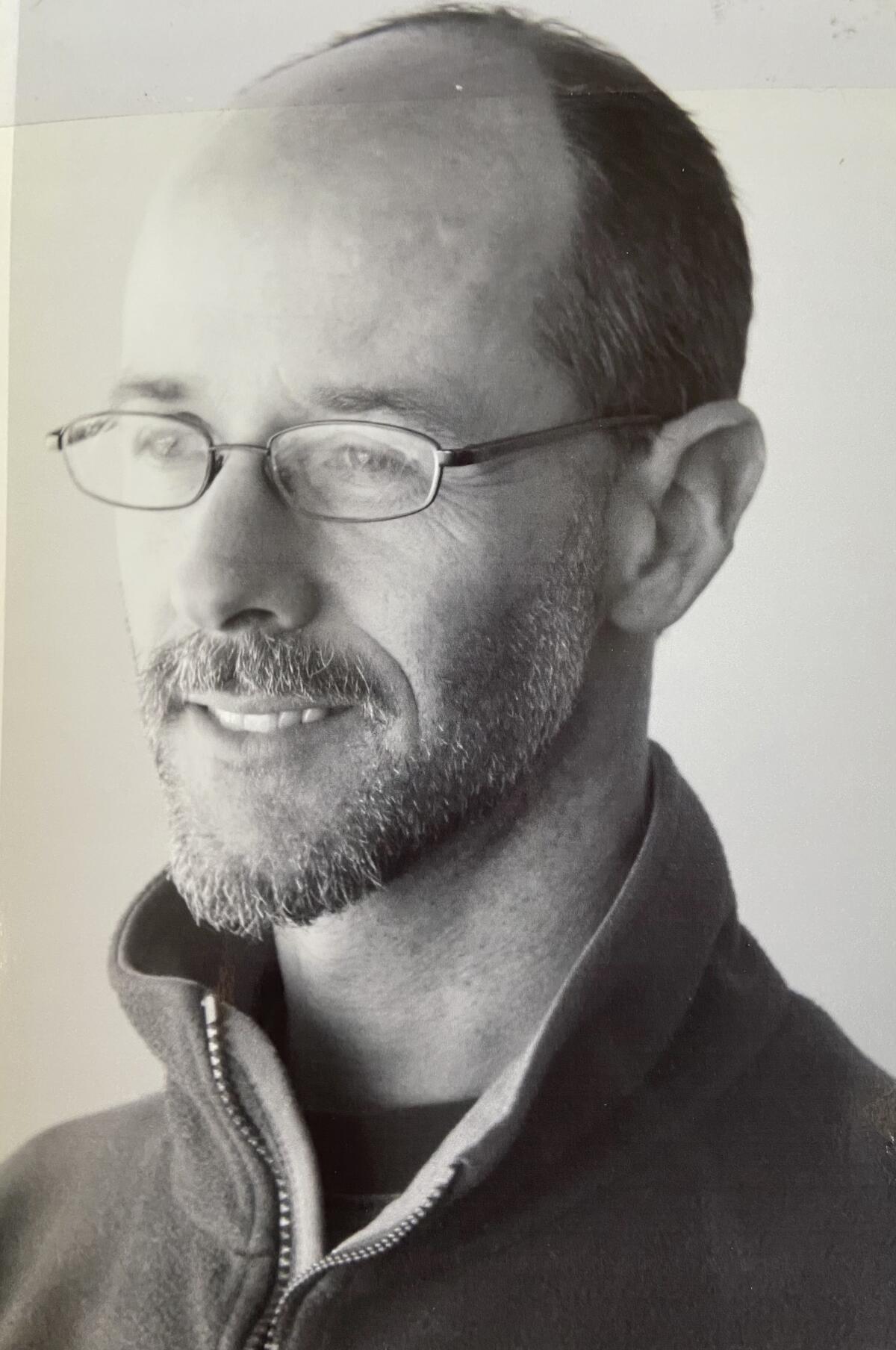

Wynn Bruce, a 50-year-old climate activist and Buddhist, set himself on fire in front of the U.S. Supreme Court last week, prompting a national conversation about his motivation and whether he may have been inspired by Buddhist monks who self-immolated in the past to protest government atrocities.

Bruce, a photographer from Boulder, Colo., walked up to the plaza of the Supreme Court around 6:30 p.m. on April 22 — Earth Day — then sat down and set himself ablaze, a law enforcement official said. Supreme Court police officers responded immediately but were unable to extinguish the blaze in time to save him.

Investigators, who spoke to the Associated Press on condition of anonymity, said that they did not immediately locate a manifesto or note at the scene and that officials were still working to determine a motive.

On April 23, Kritee Kanko, a Zen Buddhist priest who described herself as Bruce’s friend, shared an emotional post on her public Twitter account saying his self-immolation was “not suicide” but “a deeply fearless act of compassion to bring attention to climate crisis.”

She added that Bruce had been planning the act for at least a year. She wrote: “#wynnbruce I am so moved.” She got sympathetic responses as well as backlash.

Kanko and other members of the Rocky Mountain Ecodharma Retreat Center in Boulder released a statement Monday saying that “none of the Buddhist teachers in the Boulder area knew about [Bruce’s] plans to self-immolate on this Earth Day,” and that had they known about his plan, they would have stopped him. Bruce was a frequent visitor to the Buddhist retreat center in the mountains near Boulder where he meditated with the community, Kanko said.

“We have never talked about self-immolation, and we do not think self-immolation is a climate action,” the statement said. “Nevertheless, given the dire state of the planet and worsening climate crisis, we understand why someone might do that.”

On Facebook, Bruce wrote about following the spiritual tradition of Shambhala, which combines Tibetan Buddhism with the principles of living “an uplifted life, fully engaged with the world,” according to the Boulder Shambhala Center. Bruce also posted praise for Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh, a leader of engaged Buddhism, around the time of his death in January.

Bruce’s act of sitting down and setting himself on fire was reminiscent of the events of June 11, 1963, when Thich Quang Duc, a Vietnamese monk, seated cross-legged, burned himself to death at a busy Saigon intersection. He was protesting the persecution of Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government led by Ngo Dinh Diem, a staunch Catholic.

In a letter to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., whom Hanh counted as a friend, Hanh wrote that he drew inspiration from the Vietnamese monk’s self-sacrifice, saying: “To burn oneself by fire is to prove what one is saying is of the utmost importance. There is nothing more painful than burning oneself. To say something while experiencing this kind of pain is to say it with utmost courage, frankness, determination and sincerity.”

In Tibet, anti-Chinese activists have employed self-immolation as a form of protest. The International Campaign for Tibet says 131 men and 28 women — monks, nuns and laypeople among them — have self-immolated since 2009 to protest Beijing’s strict controls over the region and their religion.

Buddhism as a religion does not unilaterally condone the act of self-immolation or taking one’s life, said Robert Barnett, a London-based researcher of modern Tibetan history and politics.

“Killing yourself is considered damaging in Buddhism because life is precious,” he said. “But if a person self-immolates because of a higher motivation and it’s not out of a negative emotion such as depression or sadness, then the Buddhist position becomes far more complex.”

If self-immolation is done to help the world, it might be accepted as a positive action, Barnett said. He cited a story from the “Jataka Tales,” a body of South Asian literature concerning the prior incarnations of the Buddha in human and animal form. In that particular tale, an incarnation of the Buddha, in an act of selfless compassion, offers himself to an emaciated tigress who was so hungry that she was ready to devour her own cubs.

“But that kind of self-sacrifice is not encouraged, developed or talked about for normal people,” other than the Buddha. he said, adding that this is because of “the immense difficulty of cultivating positive motivation in any situation, let alone maintaining it under stress or in conditions of extreme pain.”

Buddhism emphasizes emotional balance, inclusiveness, kindness, compassion and wisdom, said Roshi Joan Halifax, an environmental activist and abbot of the Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe, N.M. .

“What we’re seeing today among many people is hopelessness,” she said. “What we are called to do is not to be disabled by that sense of futility, but to transform our moral suffering into wise hope and courageous action.”

Despite the pessimism that some climate activists may feel, there is reason to remain hopeful, Halifax said.

“You see that people are waking up to the magnitude of the climate catastrophe,” she said, noting that countries and corporations are moving away from damaging practices and toward clean energy.

“I feel inspired and hopeful by our ability to change and adapt in this ever-changing world,” she said. “My heart is heavy that [Bruce] did not have that kind of optimism.”

Those who knew Bruce saw a man who was kind, playful and idealistic — an avid dancer who participated in weekly events. He was also known for biking and embracing public transportation.

Bruce, who enjoyed the outdoors, brought an intensity to whatever he did, said his friend Jeffry Buechler. On Buechler’s wedding day in 2014, Bruce, on a whim, decided to go for a dip in a cold mountain lake early in the morning, he said.

Bruce also suffered lasting effects from a brain injury he sustained in a car wreck that killed his best friend about 30 years ago, Buechler said.

Marco DeGaetano, who met Bruce in the 1990s when they both attended a Universalist church in Denver, said, “Wynn seemed to have an affinity for people who needed help.”

He recalled Bruce being kind to a church member with a mental illness when others distanced themselves.

DeGaetano said he last saw Bruce about a month ago, and he seemed outgoing and friendly as always — every time he saw Bruce, “he had a smile on his face.”

Bharath reported from Los Angeles and Slevin from Denver. Associated Press writer Michael Balsamo in Washington, D.C., and researcher Rhonda Shafner in New York contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.