First person: UCLA legend Ann Meyers Drysdale shares how Title IX changed her life

Ann Meyers Drysdale was the first woman to receive an athletic scholarship at UCLA. The Hall of Famer, longtime TV basketball analyst and mother of three shares how Title IX helped shape her life and career, and what needs to be done over the next 50 years for the law to continue to have a positive impact on young girls and women.

I am one of 11 children, with five sisters and five brothers. I was a 1972 sophomore in high school in La Habra, playing seven sports when Title IX was passed. A law of 37 words that became the calling card for girls and women in sports.

I knew nothing about what Title IX was or how important it would be for my future.

Heading into 1973, I was so wrapped up with school activities, thinking about boys, learning to drive, hearing about Vietnam War, ERA, civil rights, and watching my older sister Patty play sports to understand what Title IX would mean for me.

As many celebrate the Title IX 50th anniversary, transgender athlete rights are the next frontier proving immensely difficult to sort out.

But in the 50 years Title IX has been in existence, it has opened doors for me and thousands of other women, though a handful of women traveled a more difficult road to show what was possible before the legislation was passed.

I got to see women competing at a very high level because of my sister. She played three sports at Cal State Fullerton and won the 1970 national basketball championship under coach Billie Moore.

I remember Billie Jean King (BJK) beating Bobby Riggs in a historic nationally televised tennis match, which helped liberate women all over the country. BJK and Donna de Varona (UCLA and youngest Olympic swimmer) would start the Women’s Sports Foundation when I was a senior in 1974, and I was excited to be asked to be a part of it.

I was also excited about being the only high school player to be named to the U.S. women’s national basketball team.

It was all part of a life-changing year for me because of Title IX.

My brother David played basketball at UCLA, and he came home one summer weekend in 1974 with his roommate Kenny Washington, who had returned to UCLA to go to law school before being named the new Bruins women’s basketball coach. They asked me whether I wanted to go to UCLA on a basketball scholarship.

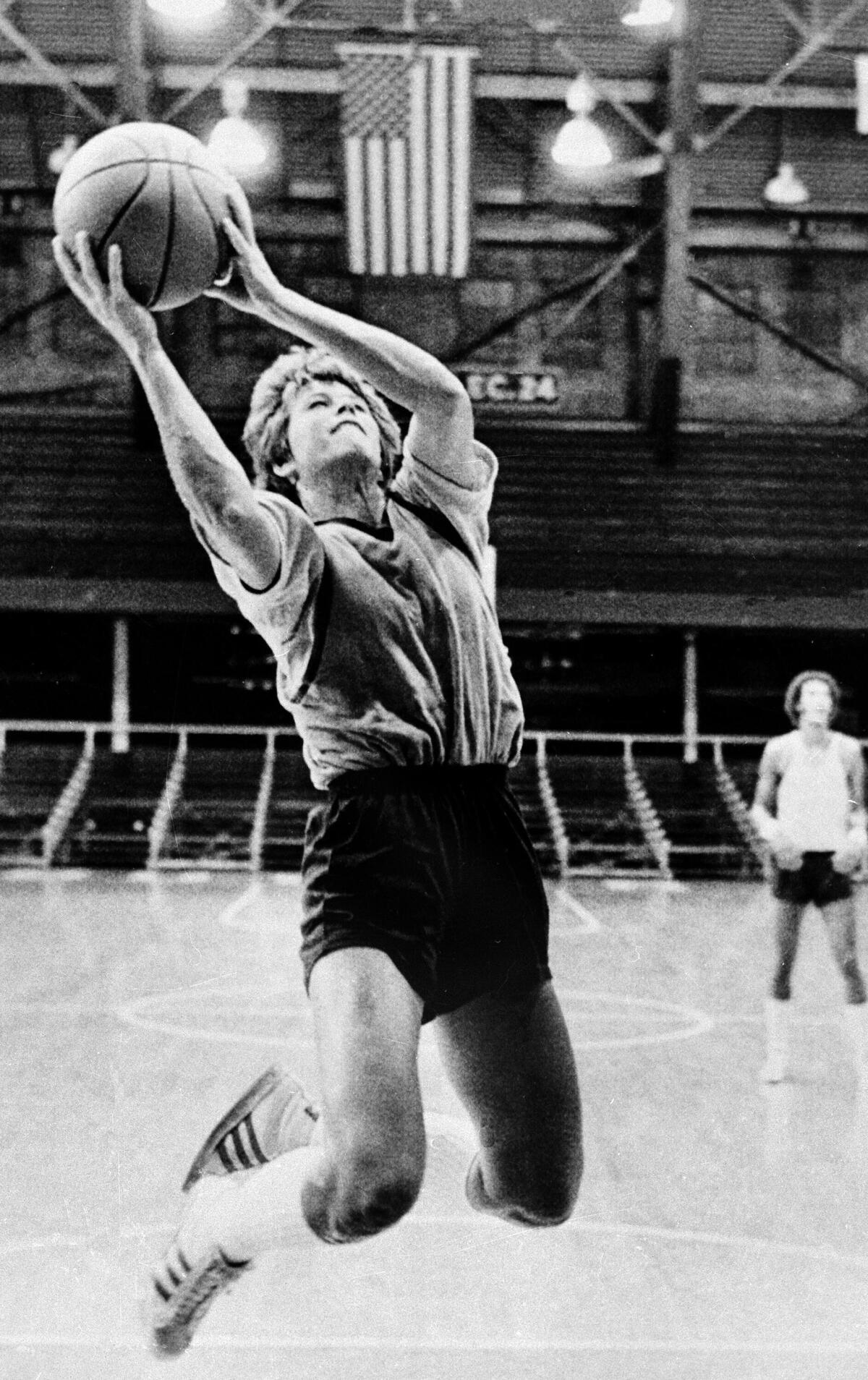

With Title IX, I became the first woman to receive a full athletic scholarship to UCLA. I would also compete in track (my first love) and volleyball.

Both David and Kenny played for “Papa” (coach John Wooden): Kenny on the first UCLA championship teams (1964, ’65), and David on the 1973 championship team.

I was playing on the national team — that would become the first U.S. women’s basketball team to play in the Olympics, at the 1976 Montreal Games — when I got to watch the Bruins and my brother win the 1975 NCAA championship. I wanted to have the same excited feeling.

I believe to this day that if I had gone anywhere else but UCLA, women’s basketball and I would NOT have received the attention that we did back in the 1970s.

At that time, UCLA men’s basketball was winning championships under Wooden (I would become an all-American like David, me a four-time selection). We became a media “human interest” story.

Yes, my brother and I made for a good story, but my teammates and I were much more than a feel-good story — we could play. And coach Wooden, who validated the women’s game, gave our program credibility.

In 1976, I was able to follow in the footsteps of Olympic greats such as Babe Didrikson, Wilma Rudolph and Wyomia Tyus. I won a silver at the Montreal Games, playing for Moore, my sister Patty’s former coach. We would win the AIAW [Assn. for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women] championship in my senior year in Pauley Pavilion with Moore as my new college coach.

In the Maryland title game, I scored 20 points, with 11 rebounds, 9 assists, and 8 steals. I held 12 of the 13 school records when I graduated with a sociology degree, and had won championships in both track and basketball.

I would become the No. 1 pick of the Women’s Basketball League, the first women’s professional league. I would stay amateur to play in the 1980 Olympics, but then I was invited to have an NBA tryout with the Indiana Pacers. David was playing then for the Milwaukee Bucks.

What an opportunity of a lifetime!

And one that would not have been possible without Title IX.

I went through the tryouts, did not make the team, but so many doors opened up for me, including being the MVP of the WBL when I played.

But Title IX isn’t just about sports. It’s about equal education and opportunity, prohibiting sex-based discrimination.

Women in sports often use social media to work around limited traditional media exposure, forge strong bonds with fans and earn endorsement money.

After playing, I started a sports broadcasting career that has spanned almost 45 years, including broadcasting six Olympics (1984, 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012, 2016). I also covered men’s and women’s Final Fours, plus volleyball, softball and other sports. I was invited to compete in four ABC-TV “Women’s Superstar” competitions (won 3 three in a row) and one “Men’s Superstars.”

I would meet my future husband, Don Drysdale, and have three children (our two sons, DJ and Darren, plus our daughter Drew). Our daughter would compete on UCLA’s track team.

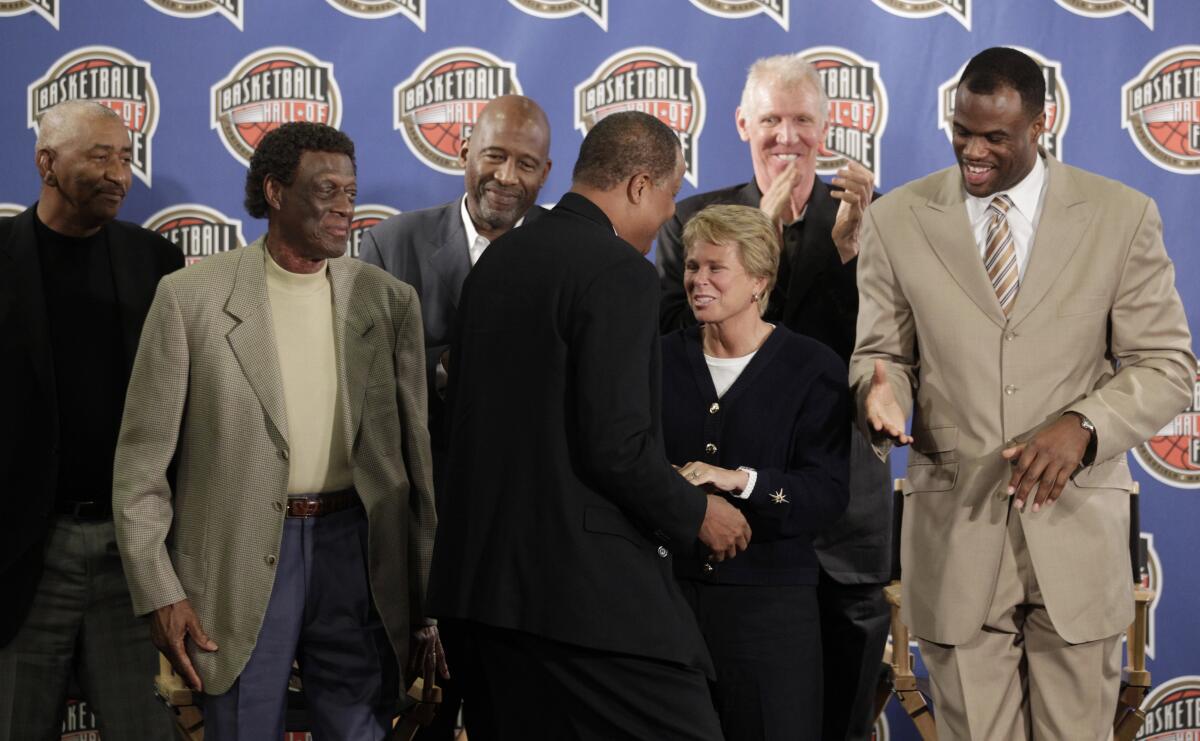

I am in 20 Halls of Fame, a national speaker on women’s sports, and continue to work in the game I love. In 2007, I was hired by the WNBA’s Phoenix Mercury to be their general manager. The team would win two titles and a third when I was Mercury vice president, while also working with the NBA’s Phoenix Suns.

Today, I broadcast for both teams.

I have much to thank Title IX for, and because of the law, so many more young girls and women now have the chance to pursue an education and play sports they love, plus they have a voice because of the legislation. There are more successful women today in corporate America that started as college athletes.

I believe in order for Title IX to continue for another 50 years that parents and coaches need to educate their daughters and sons, on what this law means and the importance of its existence for their futures.

The equality fight for women’s sports continues today as many colleges and universities are still not in Title IX compliance.

Don’t ignore its importance.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.