KYIV, Ukraine — As night fell, a lone street performer in a pool of lantern light raised her voice in song. In an inky pedestrian underpass, the only illumination was a flower seller’s display of blooms, backlit by LED lights. Dog walkers carefully affixed glowsticks to their pets’ collars. Passersby picked their way over rough cobblestones, wielding cellphone flashlights as they went.

With winter’s gloom beginning to settle over the country, Ukraine’s capital is plunged nightly into near-darkness by rolling power cuts meant to help preserve an energy infrastructure devastated in recent weeks by Russian drone and missile strikes.

As the war nears its nine-month mark, President Volodymyr Zelensky has accused his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, of “energy terrorism” — trying to break his compatriots’ spirits by plunging them into cold and darkness.

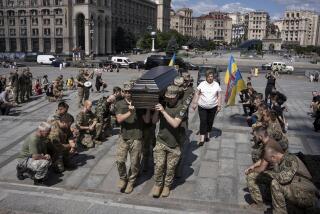

Instead, morale has soared. On Friday, rejoicing broke out across Ukraine as a Russian pullback from the strategic southern city of Kherson — and the entry of a vanguard of Ukrainian troops into the city — marked the latest in a string of humiliating defeats for Moscow’s forces.

Although Ukrainian officials warn that it could take days or weeks to clear remaining Russian troops and booby traps, the impending recapture of Kherson, the only regional capital Russia had managed to seize, marked a “historic day,” Zelensky said in his nightly address.

In Kherson, locals greeted arriving Ukrainian troops with cheers, tears and ecstatic embraces. Hundreds of miles away in Kyiv, the main square erupted in celebration — in darkness broken only by television news crew lights.

“There are grannies in cold cellars, kids who’ve forgotten what toys even look like.”

— Olena Tymchenko, a 63-year-old single mother of a teen-ager

Putin’s government has alternated between declaring that the electrical grid that powers cities and towns is a legitimate military target and denying that it deliberately takes aim at civilian infrastructure. Kremlin-linked propagandists, meanwhile, have openly gloated over the prospect of sowing hardship in a capital that Russian forces tried and failed to seize early in the war — a city where life had resumed many trappings of normality in the late summer and early fall.

Although civilian infrastructure across the country has taken heavy hits throughout the conflict, the campaign to starve Ukraine of power came to a head last month, with a blitz of missile and drone strikes hitting Kyiv and its environs. Nationwide, energy-production capacity was cut by about 40%, leaving millions facing outages.

In Kyiv and elsewhere, that has led to regular rolling blackouts meant to stabilize the grid. In some districts, scheduled cutoffs lasting four hours at a time leave people without power for up to 12 hours a day. Even in neighborhoods that have electricity, closed stores turn off their lights and extinguish most neon signage. Entire office towers and apartment blocks go dark.

In many cafes and restaurants, dining by candlelight is a matter of practical necessity rather than romance. A plethora of city landmarks usually proudly spotlighted — the golden spires of centuries-old cathedrals, the soaring column commemorating Ukraine’s 1991 independence — are ghostly silhouettes, dark outlines against a darker sky.

Dusk falls hard and early, with the sun setting a bit after 4 p.m. But earlier this week in a Kyiv park, a couple strolling hand-in-hand stood in the evening chill, gazing at a luminous full moon. Against a dark hillside backdrop, the tilting, lit-up windows of passing buses resembled some kind of avant-garde mobile art installation. Headlights pierced the murk, and just as swiftly faded.

Ukraine’s president has hinted at the possibility of peace talks with Russia, but his preconditions would appear to be nonstarters for the Kremlin.

Although the lack of power disrupts daily lives — commerce curtailed, home-schooling knocked offline, homemade meals left half-baked when the electric oven suddenly shuts down — Kyiv residents tend to stress their awareness that people living in battle zones in the country’s south and east suffer far harsher privations.

“There are grannies in cold cellars, kids who’ve forgotten what toys even look like,” said Olena Tymchenko, a 63-year-old single mother of a teenager. “How can I complain? We’re managing.”

With streetlights few and far between, a busy multilane road leading into the city turns into a white-knuckle speedway at nightfall. The accident rate has risen by a fifth; police implore pedestrians to wear a safety vest or carry a flashlight, and for drivers to stay below the speed limit.

“You need to remember that you need enough time to stop the car,” regional Police Chief Andriy Nebytov said at a briefing last week. “Please remember that it is dark on the streets!”

The Times’ Carolyn Cole is on the ground in Ukraine as residents prepare for winter’s cold amid Russian missile strikes against the nation’s infrastructure.

The biting cold of Ukrainian winter is still weeks away, although lowering gray skies, chilly fog and temperatures dipping into the 40s are a harbinger. The Kyiv municipality aims to set up 1,000 shelters that will be able to offer not only protection against bombs, but a place to warm up.

Kyiv municipal authorities caused a stir last week when they said that if the grid were to break down completely, the city of some 3 million people might have to be evacuated, primarily because water taps and sewage treatment depend on electricity. But they quickly tempered that warning with upbeat assurances that hundreds of foreign-donated generators were arriving, and repairs to airstrike-damaged power installations were proceeding as quickly as possible.

Even so, authorities urged people to think about a countryside sojourn, if they could.

“If you have extended family or friends outside Kyiv, where there is autonomous water supply, an oven, heating, please bear in mind the possibility of staying there for a while,” said Vitali Klitschko, the heavyweight boxer turned mayor.

Earlier this week, Yaroslav Boydyanski and his girlfriend, Yulia Khumara, both 20, were inspecting a popular attraction: a display of wrecked, captured Russian military vehicles set up by authorities in the square fronting the sky-blue monastery of St. Michael.

Visiting from the central city of Dnipro, the two wanted to fit in some sightseeing before dark. They weren’t bothered by the recent missile strikes or ongoing power outages, they said.

President Volodymyr Zelensky made the announcement hours after Russia said it had completed withdrawing troops from the strategically key city.

“We’re a strong people,” Boydyanski said. “We’ll survive this, and everything else.”

“We will,” Khumara said. “But you look at these things” — she gestured toward a ruined, rusted tank turret — “and you don’t forget that war is always close by.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.