PUERTO VALLARTA, Mexico — Some of the pills looked just like antibiotics. Others were unlabeled white tablets. Several mimicked well-known American pills, and a few came in sealed bottles.

They were all purchased in Mexico, at legitimate pharmacies from Tulum, at the country’s southeast tip, to Tijuana, at the northwest border with California.

And at least half of them were fakes.

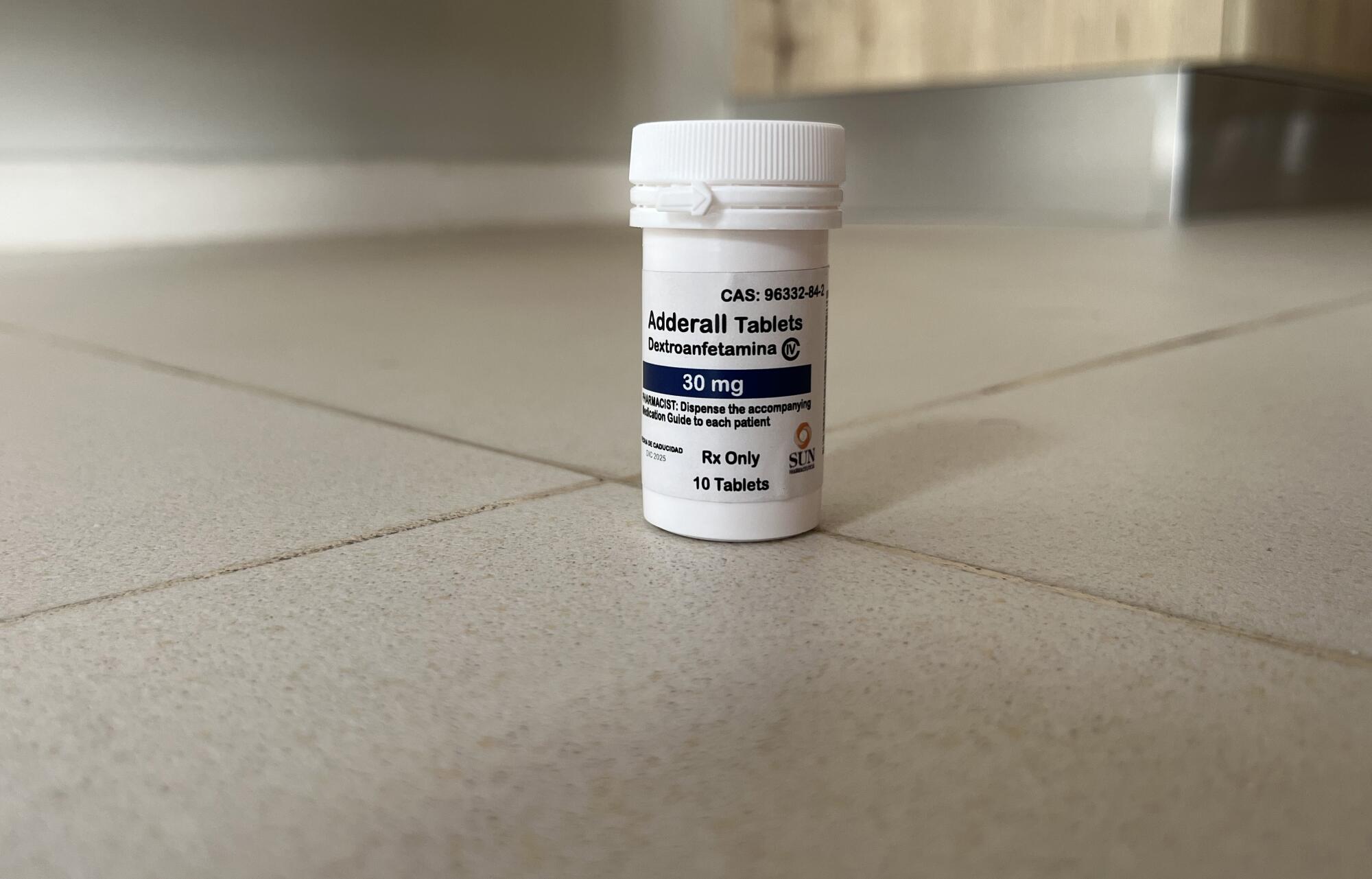

Earlier this year, The Times found that pharmacies in several northwestern Mexico cities were selling counterfeit pills over the counter, passing off powerful methamphetamine as Adderall and deadly fentanyl as Percocet and other opioid painkillers. But four more months of investigation showed the problem is much broader than previously understood.

It’s not just stray single pills that are laced with dangerous substances, but sometimes entire bottles that appear to be factory sealed. And the issue isn’t restricted to one area: It’s happening in tourist hot spots across the country, from the California border to the Yucatán Peninsula and from the southernmost edge of Texas to the Pacific Coast.

During five trips to Mexico, Times reporters purchased and tested 55 pills from 29 pharmacies in eight cities. A little more than 50% — 28 pills — were counterfeit.

More than a third of the opioid painkillers tested — 15 out of 40 — were counterfeit, the vast majority positive for fentanyl. One tested positive for a weaker medication and another tested positive for no drugs at all. Meanwhile, 12 of 15 Adderall samples tested positive for other substances, including methamphetamine and, in one case, MDMA, the designer drug commonly known as ecstasy.

Some of the pills came from drugstores in seaside destinations including Playa del Carmen, Cozumel, Tulum, Los Cabos and Puerto Vallarta. Others were purchased in Tijuana and Nuevo Progreso, border towns with booming medical and pharmaceutical tourism sectors.

In most of those locations, the pills that tested positive came from independent pharmacies, where workers sold them over the counter, one tablet at a time. But in Puerto Vallarta, counterfeits were available even at one regional pharmacy chain — the sort of place where people might expect more quality control. Both there and in Nuevo Progreso, pills purchased in sealed bottles tested positive for more powerful drugs, a possible sign of the sophistication of fakes made by cartels, which experts say are likely the source.

“This is just terrible — it shows an utter lack of control in pharmacies,” said Vanda Felbab-Brown, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who has studied drug cartels. “It’s institutionalized murder.”

It is unclear how high the death toll might actually be. Times reporting confirmed that at least half a dozen Americans have overdosed or died after taking counterfeit pills purchased from pharmacies. But because authorities in Mexico do not routinely do detailed toxicology testing, it’s impossible to know how many more people have been adversely affected.

An alert by the U.S. State Department urges American travelers to “exercise caution” when purchasing drugs from pharmacies in Mexico.

Now, given the new testing that shows how common tainted pills are in stores throughout the country, some drug-market experts worry the problem could have a far broader reach, to include tourists from outside of the Americas.

It’s often not clear whether pharmacy clerks and owners know they are selling deadly counterfeits. Some drugstore workers warned about the risk of laced pills and “homemade Adderall,” but none offered any explanation when they were contacted later.

Mexican government officials have ignored repeated requests for comment, except for one federal prosecutor who said this month that her office would comment only if reporters revealed the names and locations of the pharmacies they visited.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration has known about the problem since at least 2019.

Last month, after speaking for half an hour at a business conference in Beverly Hills, DEA Administrator Anne Milgram refused to answer questions from Times reporters. When asked whether she was aware of reporting about Mexican pharmacies selling fentanyl- and methamphetamine-tainted pills, she left without responding.

Later, she offered comment through a spokeswoman via email, without addressing the specific questions posed.

“One of the greatest threats to the safety and health of Americans today are fake prescription pills sold as legitimate medication when in fact they are not — they are fentanyl,” Milgram’s statement said. “In 2022, the DEA seized over 58 million pills containing fentanyl in the United States. We are continuing our enforcement and education efforts on this important issue to save lives.”

On a late spring day in Puerto Vallarta, tourists carrying Starbucks cups and cans of Michelob Ultra strolled along the bougainvillea-lined avenues of the bustling Zona Romantica. The city of nearly a quarter of a million people is on the Pacific Coast, roughly halfway between Mexico’s northern and southern borders.

It’s better-known as a resort town for gay men than a hot spot for medical tourism. But in between its bars and boutiques are dozens of drugstores, many willing to sell powerful medications over the counter.

Mexico has long been a mecca for Americans seeking easier and cheaper access to medications that require a prescription in the U.S. — drugs such as Viagra, Xanax and tramadol. In theory, oxycodone and amphetamines are much more tightly controlled. If a store is even willing to sell them over the counter at all, that’s a red flag that they might not be authentic.

Between the time U.S. officials knew about counterfeit meds at Mexican pharmacies and the time they posted a warning about the threat, Americans died.

And yet, in the cities reporters visited, finding stores that would sell them without a prescription proved easy. Sometimes, reporters compiled a list of potential pharmacies to visit by scouring Reddit, following emailed tips or browsing online pharmacy reviews. Other times, the starting point was a Google Maps search for nearby pharmacies.

To buy pills for testing, reporters walked into drugstores in tourist areas and asked — usually in English — for Adderall and either Percocet or oxycodone. Sometimes clerks would say they didn’t have the pills, but often they would pull out a chart of offerings.

The laminated charts didn’t always include the requested medications, but typically workers would then go into a backroom or reach under a counter to grab hidden pill containers. In some cases, pharmacy employees said to come back after the daily delivery came in, or they made a quick call to have tablets brought over from off-site.

Afterward, reporters ground up a portion of each pill and used test strips to determine whether they contained fentanyl or methamphetamine, following a protocol recommended by UCLA researchers who conducted their own testing earlier this year.

Samples of about one-third of the medications were later tested at a laboratory with a mass spectrometer, which helped confirm initial results and identify other adulterants — including MDMA and caffeine.

The results expand on findings released earlier this year by the UCLA research team, which used an infrared spectrometer to show that 20 out of 45 pills purchased in four northwestern Mexico cities were counterfeits containing fentanyl, methamphetamine or heroin.

“We don’t know exactly when this started, and we don’t know how widespread it is,” Chelsea Shover, the study’s senior researcher, told The Times in February. “The most important unknown is probably how many people have died or had serious health consequences from it, and we don’t have any idea.”

Since then, reporters have worked to answer some of those questions, first by uncovering evidence of multiple overdoses and several deaths, and now by showing the problem is far more widespread than was previously known.

Though The Times found counterfeits in each of the eight cities where they did testing, there were major variations when it came to availability, cost and the odds of a given pill being fake.

In popular areas of the northernmost cities reporters visited — Cabo San Lucas, San José del Cabo, Tijuana and Nuevo Progreso — there were often multiple pharmacies per block. Most of those visited were willing to sell oxycodone, Percocet or Adderall over the counter, one pill at a time, typically for less than $20 each. In Nuevo Progreso, entire bottles of oxycodone that turned out to be counterfeit could be bought for as little as $40.

Farther south, in the upscale resort cities of the Riviera Maya, fewer pharmacies would sell powerful narcotics without a prescription. Many of those that did would only sell multi-tablet blister packs or entire bottles of pills marketed as Percocet or Adderall, sometimes at exorbitant prices topping $700 U.S. per bottle.

Reporters bought and tested pills in three cities in the region: Cozumel, Playa del Carmen and Tulum, where pharmacies that were willing to sell individual pills typically charged between $15 and $40 each.

Pills sold as Adderall proved consistently unreliable across the country, but the odds of a tablet sold by a pharmacy as oxycodone or hydrocodone being a dangerous fake varied from city to city.

Each of the several opioids reporters tested in Cabo San Lucas came up positive for fentanyl; none did in Puerto Vallarta. In Puerto Vallarta, one sample of hydrocodone — commonly known by the brand name Vicodin — turned out to be a weaker medication instead.

In 2018, the family of a man killed by a fentanyl pill from a Mexican pharmacy called on U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein and then-Sen. Kamala Harris to act. Little has been done in the intervening years.

UCLA researchers earlier this year purchased one sample of supposed oxycodone that turned out to be heroin, also from a drugstore in an unnamed city along the western coast.

At one pharmacy near Tijuana’s red light district — in a store where none of the medications tested positive for fentanyl — a friendly clerk in a college sweatshirt even warned visitors that other shops sold laced pills.

Just 15% of the opioids that reporters tested in the Yucatán Peninsula turned out to be fentanyl. That was partly because some stores there appeared to be getting legitimate pills from nearby Guatemala and reselling them. Several pharmacies offered purple oxycodone in blister packs bearing the name of a Guatemalan drugmaker, along with a Guatemalan drug register number.

None of the blister packs reporters purchased in any city tested positive for other drugs. But in Nuevo Progreso, a sealed bottle of Percocet tested positive for fentanyl. Even more troubling, in Puerto Vallarta every sealed bottle of medication reporters purchased — including four bottles of supposed Adderall and one of supposed hydrocodone — was counterfeit, testing positive for methamphetamine and tramadol, respectively.

Usually, there were obvious red flags: Several had typos in their labels, and a few were entirely in English with complete American National Drug Code, or NDC, numbers.

To Felbab-Brown, the Brookings Institution cartel expert, the sophistication and prevalence of counterfeit drugs at pharmacies is reminiscent of the way Mexican criminal organizations infiltrated the fishing industry a few years ago. The Sinaloa cartel “would go to processing plants and they would say, ‘Look, we’ll burn down your plant and kill your family if you don’t sell our fish,’” Felbab-Brown explained.

Other cartels copied Sinaloa’s move, and the problem spread across the country. Now, Felbab-Brown worries that something similar may be happening in Mexico’s pharmacies — and that there could be implications outside the Americas.

When The Times’ initial reporting in February uncovered a counterfeiting problem on Mexico’s western coast, it was American and Canadian tourists who were most likely to be affected, she said. But because the problem is not limited to that region, it could affect a different population of visitors.

“The whole Mayan Riviera is huge for European tourists,” Felbab-Brown said. “How much is this going to expose them?”

In light of The Times’ findings in Mexico, she said, governments in Europe should be proactive.

“They need to mount a really serious warning campaign,” she said, “as opposed to erring on the side of not informing people about a major risk.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.