Wreckage from Tuskegee airman’s plane that crashed during WWII training recovered from Lake Huron

DETROIT — A team of divers have been trolling the deep, cold waters of Lake Huron off Michigan’s Thumb for several weeks each of the past few years searching for scattered pieces of aviation — and Black military — history.

Their target is the wreckage of a World War II-era fighter plane flown by a member of the famed Tuskegee Airmen that crashed during training nearly 80 years ago near Port Huron, about 60 miles northeast of Detroit.

So far, the plane’s bullet-riddled propeller and hundreds of other pieces have been recovered. Organizers this week hauled the P-39’s 1,200-pound mussel-encrusted engine from about 30 feet below the surface of the the lake, which is home to scores of sailing vessels, tankers and other ships that sank over the last several centuries.

Once restored, the engine, like other parts of the plane, eventually will be exhibited at the Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum at the Coleman A. Young International Airport on Detroit’s east side.

“We’re doing some finalizing of mapping things in terms of what all is there,” said Carrie Sowden, archaeological and research director at the National Museum of the Great Lakes in Toledo, Ohio. “As we prepare for these major lifts, we’re finding all these small pieces. When we’re done we’re going to have a complete understanding where every single piece came from.”

This article was originally on a blog post platform and may be missing photos, graphics or links.

The airmen were the nation’s first all-Black air fighter squadron. They trained and fought separately from white fighter units because of segregation in the U.S. military. Their unit was based in Tuskegee, Ala., but Michigan served as an advanced training ground during the war.

On April 11, 1944, 2nd Lt. Frank Moody, 22, of Los Angeles was flying over Lake Huron. It’s believed his machine guns were not in sync with the rotation of the P-39’s propeller. When Moody fired the guns, the slugs struck the propeller, causing the plane to crash into the waters below.

His body washed ashore a few months later, but the plane’s wreckage lay scattered along the lake bottom, only disturbed by the movement of the waves and water until 2014 when it was discovered.

In 2018, the state issued an archaeological recovery permit to the museum. Later that year, dive and recovery teams began mapping and bringing pieces of the plane up, including the tail, guns, gauges and munitions.

“The aircraft is largely disarticulated,” according to Wayne Lusardi, Michigan’s state maritime archaeologist with the Department of Natural Resources and organizer of the recovery effort.

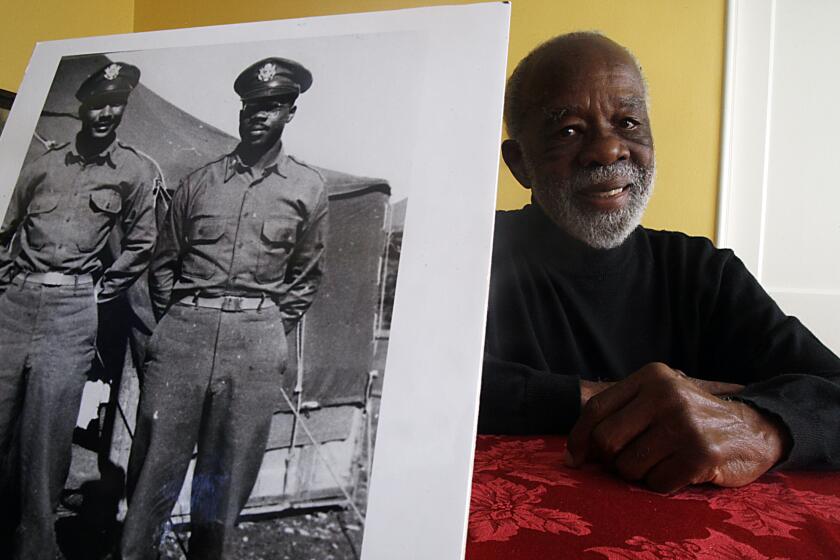

Lumpkin, a native Angeleno, was an intelligence officer with the famed squadron of Black aviators known as the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II.

“It’s broken, spread out over almost a half-a-mile underwater and consists of thousands of pieces,” he told the Associated Press on Thursday after the engine was lowered into a chemical solution inside the Tuskegee Airmen museum’s hangar. “There’s still a good amount of the plane that’s still on the bottom.”

The Detroit News reported that divers also located part of the plane’s landing gear wheel well and wing flap motor.

Depending on the condition of the artifacts, restoration could take years, according to Isis Gillespie, the museum’s conservator of the P-39.

“Because the engine is intact, you know it crashed very shallow in the lake ... and it was in fresh water so it helped preserve it a lot more,” Gillespie said. “This find is so important for Black history to find out how Tuskegee airmen fought for this country and how they fought a war at home,” Gillespie said Thursday.

Moody’s sacrifice in Lake Huron also should be remembered, added Lusardi.

“It’s sometimes very easy to forget that this was a place where a young man died who gave his life for this country,” Lusardi said. “It really is going to be a memorial to the African American airmen that died here, that trained here in Michigan.”

* Pride and painful memories mix as members of the Tuskegee Airmen head to the inauguration.

Fifteen Tuskegee airmen were killed while training in Michigan, including five pilots lost in Lake Huron and one in the St. Clair River, according to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

At least three other planes flown by Tuskegee Airmen remain in Lake Huron, according to Diving With a Purpose, a Tennessee-based group that focuses on the maritime history of Black Americans.

A monument dedicated to Moody and other Tuskegee Airmen who died in Michigan during World War II training was unveiled in 2021 near the international Blue Water Bridge in Port Huron.

Tuskegee Airmen and their aircraft have been referred to as “Red Tails” for the red-painted wings of their airplanes. Hollywood producers used the name as the title of a 2012 film showcasing the unit’s struggles and its accomplishments.

President George W. Bush awarded the Tuskegee Airmen the Congressional Gold Medal in a ceremony at the Capitol Rotunda in 2007.

The Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum is working to start a capital campaign to raise funds for a new building with room to display aircraft flown by the airmen, said Brian Smith, the museum’s president and chief executive.

“Tuskegee Airmen are known for their valor and excellence in fighting the Germans in the air war over Germany in World War II,” Smith said. “That story is being told, and has been told, but what we haven’t heard are about the accidents in training that the airmen suffered. This is an exhibit that’s when it’s conserved can tell the story of African Americans — the complete story — from training, combat, then what they did after the war.”

Associated Press writer Ken Kusmer in Indianapolis contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.