SIEM REAP, Cambodia — The elderly woman was weaving baskets at home when a group of strangers arrived at her front gate, requesting her help on a national mission.

They spent the next two hours that January afternoon asking 74-year-old So Nin about growing up amid the ruins of the Angkor kingdom and her memories of the ancient monuments built by the Khmer empire before its collapse in the 15th century.

Four of the visitors returned a few weeks later, carrying books, binders and a laptop filled with photographs of artifacts from that era, many of which they believed to have been stolen and sold overseas.

They flipped through photographs — a Buddha, a stoic guardian, a three-eyed goddess — hoping So might recognize them. But she kept shaking her head no.

Then one gave her pause: a stone slab featuring the Hindu god Vishnu reclining against a giant snake, which today is on display in Pasadena as part of the Asian art collection at the Norton Simon Museum.

Her eyebrows furrowed as she leaned forward to contemplate the carving.

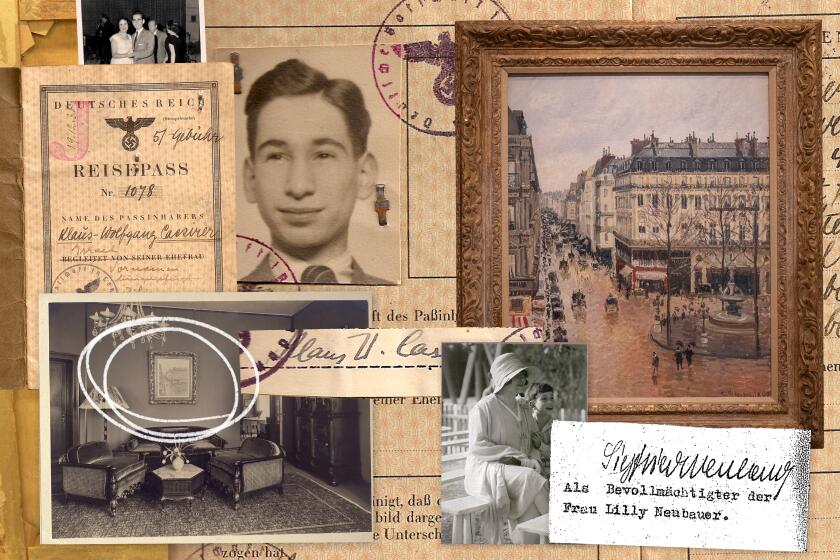

A Jewish family’s quest to reclaim a masterpiece painting stolen by the Nazis takes them across oceans and continents, into courts and back through time.

“Can you show us where you saw it?” asked one of the visitors.

The site was just a few miles away at the Ta Keo temple, but she hadn’t been there in more than 50 years. They agreed to visit it together the next morning.

The sleuths — a 55-year-old American attorney named Bradley J. Gordon and three Cambodian women working for him — are at the helm of a broadening expedition to recover thousands of artifacts that disappeared from the country’s temples during a civil war, genocide and decades of turmoil that followed.

The last time such artifacts were approved for export was during World War II, when Cambodia was occupied by Japanese forces. The government says any other objects outside Cambodia had been looted.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

The wholesale plunder started in the late 1960s, as soldiers and local gangs combed through the nation’s temples for statues, carvings and other objects of cultural significance to smuggle across the border to Thailand. From there, the objects were sold to art brokers, private collectors and the world’s largest museums in what the country regards as the biggest art heist in history.

Now Cambodia is accelerating its efforts to bring back the sacred artifacts.

“Our cultural heritage should be owned by us,” said Huot Samnang, director of antiquities at the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts. “They are our spiritual ancestors, so they should come home.”

The country scored a major victory in December, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City agreed to return 14 pieces from its collection.

Survivors of the Khmer Rouge are some of the most vocal opponents to the Cambodian People’s Party that has ruled the country for almost 40 years.

But there is much more work to be done. Working for the Culture Ministry, Gordon and his team have been scouring the sanctuaries and neighboring villages for evidence that hundreds of antiquities now on display in U.S. museums had left the country illegally.

The carving that caught So’s attention is one of 40 objects of interest at the Norton Simon. The team is also investigating 48 artifacts at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and 90 in other California institutions, including 81 at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco.

“This is a new chapter of our approach,” Gordon said.

As planned, So and the investigators climbed into a minivan for the 10-minute drive to Ta Keo, which was built for a boy king in the 10th century and abandoned after a lightning strike that was deemed an ill omen.

The last time So was there, the temple was surrounded by jungle foliage, and the stones were a glossy black.

Since then, most of the trees had been cleared. The crumbling stones had faded to brown and gray. The Vishnu carving that had impressed her as a young woman was missing from its spot above the temple entrance.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“It was beautiful,” she said. “I loved it.”

So’s recollection alone was not enough to request the return of the artifact from the Norton Simon.

But if villagers can identify where a sculpture or object once stood, Cambodia can conduct an excavation to look for physical proof of looting — a fragment or plinth or limb left behind like a missing piece of a jigsaw puzzle.

Tracking down each artifact is a demanding task. Some were unknown to most of the country until they showed up in photos of art collections overseas. Cambodia’s own written records of the spiritual objects that once adorned its 4,000 sacred temples disappeared during the war.

Were there any other elderly villagers who might corroborate So’s account?

“They’re all dead,” she told the researchers.

The quest to retrieve the country’s lost antiquities began with two mythical warriors locked in combat.

The stone characters from the ancient Hindu epic of Mahabharata had once stood in a sanctuary in the 10th century temple complex of Koh Ker, surrounded by jungle in northern Cambodia. But by the time Simon Warrack, a British stonemason with a fascination for ancient ruins, stumbled upon the scene in 2007, all that remained of them were the four feet, still attached to pedestals.

Based on the unique wide-set positioning of the feet and a dangling strip of carved cloth, Warrack traced one of the missing figures — the divine fighter Bhima — to the Norton Simon, which had purchased it from a New York art dealer in 1976. Warrack sent his findings to Cambodian authorities, but the government was hesitant to act on his research alone.

“The whole idea of restitution was a gray area — who owned things and who had stolen things, and why things were where they were,” he said. “People stepped very carefully at the beginning, because they didn’t want to make things worse.”

In 2011, a French archaeologist identified the other missing warrior as Duryodhana — a statue Sotheby’s had planned to auction off for at least $2 million until Cambodia alleged it was stolen and asked the U.S. government for help getting it back.

That was when Gordon got involved in tracking down Cambodia’s lost treasures.

The Connecticut native and Harvard Law graduate had run a Bangkok art gallery and two vegetarian restaurants in Cambodia before opening a law practice there. When he read about Cambodia’s difficulties getting back the Duryodhana, he offered his help and got a job as a consultant for the U.S. Department of Justice.

“The Duryodhana was really the beginning of the restitution renaissance,” Gordon said. “At that point, we were a small part of the story.”

For the last six months of 2012, Gordon searched Koh Ker for witnesses who might remember the disputed sandstone statue, conducting more than 100 interviews to uncover the local smuggling network responsible for the theft.

After a lengthy court battle, Sotheby’s agreed to return the Duryodhana. Taking a cue, the Norton Simon agreed to give back the Bhima.

In June of 2014, both sculptures — along with another god from the scene, Balarama, that was recovered from Christie’s auction house — were unloaded at the airport in Phnom Pehn, decorated with flowers and driven through the streets of the capital on the flatbed of a truck under “welcome home” banners.

Warrack, who attended the homecoming, explained its significance for Cambodians: “They lost 20% of the population during the genocide. None of those people are coming back. They also lost thousands of statues and sculptures. Those can come back.”

One of the people Gordon interviewed in the Duryodhana case was a former Khmer Rouge foot soldier named Toek Tik, who confessed to stealing hundreds of sacred objects and said he wanted to repent by helping retrieve them.

Soon he would become a key informant for the Cambodian government, under the code name Lion.

In 2018, after the Cambodian government made Gordon a legal advisor on repatriation, the two men began meeting frequently, often traveling to temples where Lion pointed out the former locations of artifacts he had looted.

Danny Kim, a Fresno police sergeant, was inspired to start a traditional Khmer night market after a trip back to Cambodia with his father.

In the summer of 2021, the meetings took on a greater urgency: Lion was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

“He made this decision to just transfer everything he had in his mind to us,” said Gordon, recounting how he and Lion would meet for days on end in Gordon’s apartment in Siem Reap.

Before his death later that year, Lion was able to point authorities to dozens of looted artifacts he recognized from museum catalogs and other photographs.

Many of those pieces passed through another known linchpin in the illicit antiquities trade, the British art dealer Douglas Latchford.

Cambodia’s looted treasures

For decades, Latchford had enjoyed a reputation as a dedicated patron and scholar of Cambodian art, but he came under scrutiny by U.S. federal prosecutors for his role in supplying the Duryodhana statue.

In 2019, he was indicted for trafficking looted objects and falsifying documents to cover their tracks. He died before trial the following year.

His personal collection of antiquities, valued at more than $50 million, was passed to his daughter, who agreed to give it back to Cambodia. In 2021, the Denver Art Museum returned four other pieces linked to Latchford.

Netscape founder Jim Clark agreed to send back 35 artifacts worth more than $35 million, and the family of pipeline billionaire George Lindemann returned 33 items worth $20 million.

The returns have united most of the supporting cast of the stone showdown between Duryodhana and Bhima, which are now on display at the National Museum in Phnom Penh.

Gordon is still seeking the ninth and final figure from the tableau, a statue of the Hindu deity Krishna.

“This whole project means so much to the Cambodians in terms of healing, what you do after war and how do you recover,” he said. “Now that I’ve spent so much of my life on this, it just makes sense to continue.”

Between visits with So, Gordon stopped by a two-story house along the Siem Reap River.

Accompanying him were three of his researchers, who didn’t want their names published because of the sensitivity of cases they are investigating. In the field, they go by code names: Tida, or beautiful woman; Kanha, which means September; and Sralao, a reference to the slender trees that grow around the temples.

They had come to the Angkor research center of the French School of the Far East to talk with one of its experts, Sophie Biard, and show her the photograph of the Vishnu that So had pinpointed.

“The style is not accurate for Ta Keo,” Biard said. “It’s possible it’s just the same iconography.”

Gordon and his researchers digested the information: The carving So had remembered from the temple probably wasn’t the piece in Pasadena. Vishnu depictions were common across Cambodia.

Biard promised to investigate further, and a few days later, she messaged Gordon with some surprising news.

While combing through the organization’s archives, she had discovered a photograph taken in 1969 at Preah Vihear, a temple complex near the borders of Thailand and Laos. It was a carving that looked identical to the one at the Norton Simon.

So had inadvertently led Gordon and his team to photographic evidence that the piece they were looking for had been in Cambodia long after the end of the legal export market.

“This job takes tremendous patience,” Gordon said. “After five or six times, you’ll hit something.”

With the archival photograph as proof, the piece has become a priority in Cambodia’s repatriation efforts. In March, Gordon requested all provenance documents — the recorded ownership history of a piece of art — for Cambodian objects at the Norton Simon and Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Leslie Denk, Norton Simon’s vice president of external affairs, said the museum is researching the ownership histories of its Southeast Asian art and plans to make the information available online next year.

She directed The Times to a 2010 book on the Norton Simon collection, which said the museum had purchased the Vishnu carving in 1975 for $4,000. The seller: Latchford, the disgraced dealer who died before his trafficking trial could begin.

A spokesperson for LACMA said the museum is reviewing Gordon’s inquiry. The museum declined to provide provenance documents to The Times.

A spokesperson for the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco said the institution has been working with Cambodia to identify art that may have been stolen.

The growing scrutiny over looted objects worldwide has broadened the debate on ownership from a purely legal quandary into a moral one.

“It’s become clear over the last 15 or 20 or 25 years that some dealers are extraordinarily scrupulous, and some dealers are not,” said Chase Robinson, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art, which in 2022 adopted a new ethics policy under which it will repatriate stolen objects. “The standards have really changed.”

Gordon said he’s hoping that will lead to more cooperation from art institutions to actively identify stolen objects in their collections and lower the burden of proof placed on Cambodia.

Two architectural lintels have been part of the Asian Art Museum’s collection in San Francisco since the 1960s. Now they are being returned to their homeland.

“We don’t want to have to show evidence for every single statue in order to get it back,” Gordon said. “Our message to the museums is that this is hard work. We need to do a lot of interviews. But in the meantime, they should help us.”

As more cultural artifacts have arrived back in Cambodia, the Ministry of Culture has debated what to do with them. Space is running out, with more than 33,000 in storage or on display at museums around the country.

Gordon said the country plans to expand its museums and train its first curators. Some Cambodians are also hopeful that spiritually significant figures can eventually be returned to the temples they once occupied.

But while the recent repatriations have stymied the black market, looters are still active, Gordon said. That has prevented Gordon and his team from divulging too much information publicly.

LACMA and UCLA’s Fowler Museum ponder repatriation of so-called Benin bronzes stolen during an 1897 slaughter by British colonists.

At each new site, the team approaches the guards and guides to ask about the nearest village, looking for residents in their 70s and 80s who may remember seeing statues before they were looted. Some give vague answers, while others shrug before offering one name. Not many of that generation are left.

With locals at their sides, Gordon and his team page through the photographs, hoping to find another source as open and knowledgeable as Lion.

“We need to find the people who dug stuff up, put it on trucks and took it out,” Gordon said. “We just haven’t broken the code yet.”

On the day So visited the Ta Keo temple with Gordon and his researchers, she told them that ancient statues appear in her dreams. Her memories are so vivid that when she closes her eyes, she can see the gods of her childhood.

Still, she mourns the loss of the Vishnu carving.

“I can’t believe someone would take it,” she said.

But, it turned out, whoever had carried it away all those years ago likely had more benevolent motives than a thief.

During the civil war, workers from the Ministry of Culture and the French School of the Far East took hundreds of pieces from local temples and stashed them away nearby at the Angkor conservatory. Behind barbed wire and watchtowers, the ancient treasures remained there for decades, despite a few armed break-ins over the years.

The Vishnu was almost certainly one of them and now appears to be on display at the Angkor National Museum. Biard told Gordon that it perfectly matched So’s description and that documents said it was taken from the Ta Keo temple.

But So wasn’t entirely certain when one of Gordon’s researchers recently stopped by her house with a photograph of the carving.

The team plans to take her to the museum — just a 20-minute drive from where she lives — to see the Vishnu in person and confirm whether it is indeed the one she remembers from all those decades ago.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.