U.S., Canada and Finland look to build more icebreakers to counter Russia in the Arctic

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The United States, Canada and Finland will work together to build up their icebreaker fleets as they look to bolster their defenses in the Arctic, where Russia has been increasingly active, the White House announced Thursday.

The pact announced at the NATO summit calls for enhanced information sharing on polar icebreaker production, allowing for workers and experts from each country to train in shipyards across all three, and promoting to allies the purchase of polar icebreakers from American, Finnish or Canadian shipyards for their own needs.

Daleep Singh, the White House deputy national security advisor for international economics, said the agreement would reinforce to adversaries Russia and China that the U.S. and its allies will “doggedly pursue collaboration on industrial policy to increase our competitive edge.”

A leaky, fire-prone icebreaking ship slogs 11,500 miles from Seattle to Antarctica yearly to reach scientific bases. This year’s trip was especially grueling.

Beijing has sought to tighten its relationship with Moscow as much of the West has tried to economically isolate Russia in the aftermath of its February 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

“Without this arrangement, we’d risk our adversaries developing an advantage in a specialized technology with vast geostrategic importance, which could also allow them to become the preferred supplier for countries that also have an interest in purchasing polar icebreakers,” Singh said. “We’re committed to projecting power into the high latitudes alongside our allies and partners. And, that requires a continuous surface presence in the polar regions, both to combat Russian aggression and to limit China’s ability to gain influence.”

Singh noted that the U.S. has only two icebreakers, and both are nearing the end of their usable life. Finland has 12 icebreakers and Canada has nine, while Russia has 36, according to U.S. Coast Guard data.

A reporter and photographer ride from Seattle to Vallejo, Calif., on the Polar Star, which falls apart on its round trip to Antarctica each year.

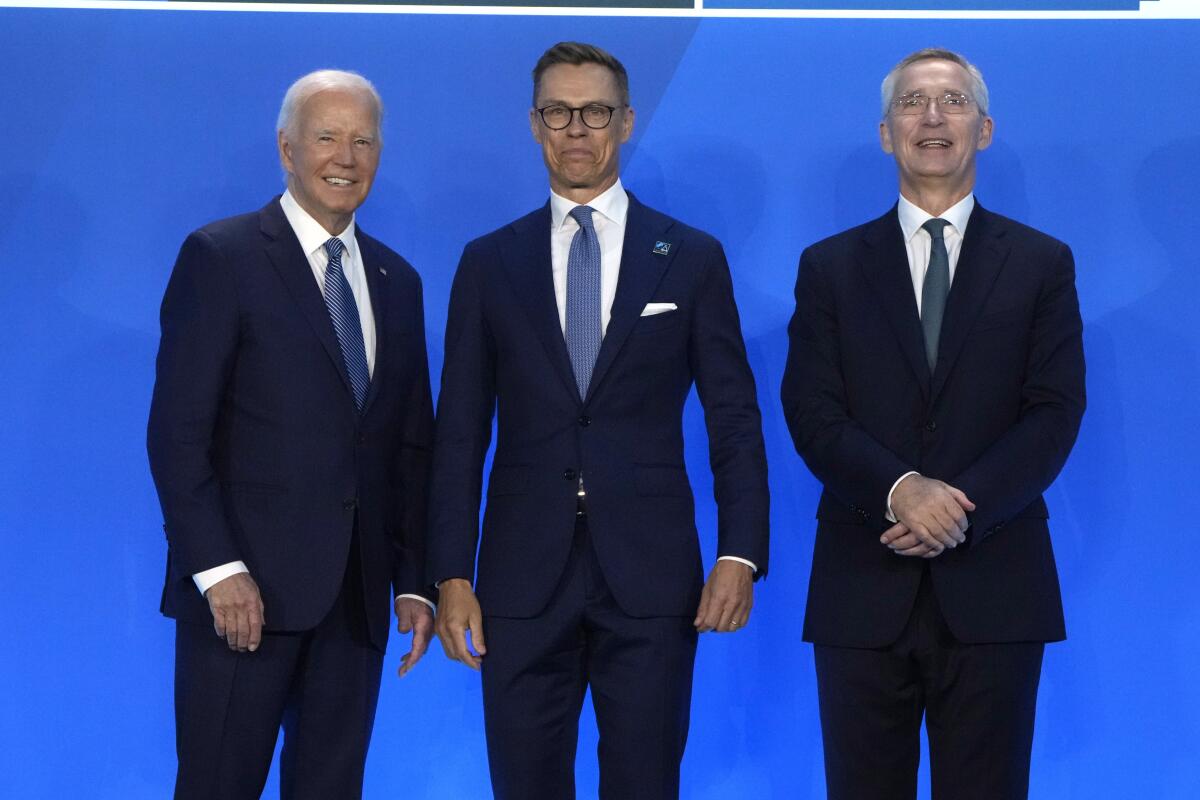

President Biden, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Finnish President Alexander Stubb discussed the pact on the sidelines of this week’s summit, which focused largely on the alliance’s efforts to counter Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

During a talk in February at Rand Corp., Coast Guard Vice Adm. Peter Gautier said the agency has determined it needs eight to nine icebreakers — a mix of heavy polar security cutters and medium Arctic security cutters. Gautier said some test panels were being built in Mississippi and full construction of an icebreaker is slated to begin this year.

As climate change has made it easier to access the Arctic region, the need for more American icebreakers has become more acute, especially when compared with the Russian fleet.

At the 75th anniversary meeting, Ukraine wins promise of new air defense systems and Europe-based military training. But not membership in the transatlantic alliance.

According to a Government Accountability Office report, the U.S. hasn’t built a heavy polar icebreaker in almost 50 years. The 399-foot Coast Guard Cutter Polar Star was commissioned in 1976 and the 420-foot Coast Guard Cutter Healy was commissioned in 1999.

Building an icebreaker can be challenging because it has to be able to withstand the brutal crashing through ice that can be as thick as 21 feet and wildly varying sea and air temperatures, the report said.

Singh said the U.S., Canada and Finland would sign a memorandum of understanding by the end of the year to formalize the pact.

Madhani and Santana write for the Associated Press.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.