When my cell rang, an unfamiliar number popped up on the screen. Normally I ignore these calls, certain my service provider has sold my information to half the country’s telemarketing companies. This time I picked up.

It was a therapist I had used as a source on a story about mental health. He had watched a couple of my recent appearances on CNN regarding the death of George Floyd and was worried about me. It was not only a kind gesture but one that carried with it a great deal of wisdom.

I was suppressing trauma and anger I didn’t even know I had.

I’ve been so busy covering the unjustifiable deaths, murders, of black and brown people over the years that I had grown accustomed to ignoring the toll it had taken on me as a black journalist. In journalism school they teach you the importance of removing yourself from the story. But there aren’t any courses on managing your mental health when you are repeatedly reflected in gut-wrenching stories.

Or, in the case of CNN’s Omar Jimenez — the black reporter who was arrested while covering the uprising in Minneapolis — you become part of the gut-wrenching story you’re covering.

Yamiche Alcindor of PBS told me on Saturday that she’s noticed a change in her own emotional connection to these particular tragedies over the years, beginning with the murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012.

“I’m from Miami and I have cousins who went to school with him, so I felt empathy,” she said. “At the same time, the journalist in me was covering George Zimmerman and his family with objectivity and professionalism. During Ferguson I started getting sadder. This time around, as someone who is married and wants to start a family one day, I feel like I got in a car accident. I survived, but I can see all of the air bag, which is unnerving. Then I get back in the car and get in another car accident, and the airbags go off again. They keep going off.”

“I feel this story in my bones. I wake up in the middle of the night crying at times.”

“I feel this story in my bones. I wake up in the middle of the night crying at times. I’m experiencing a different me.”

The sleepless nights are a recurring theme among journalists of color who have made deaths of persons of color their unofficial beat. I haven’t slept more than six hours in nearly a week. Suzette Hackney, director of opinion and community engagement for the Indianapolis Star, told me, “I walked six miles today trying to beat back the sorrow and depression.”

“I was on furlough this week,” she continued, citing a company mandate that takes her off the job for one week this month because of the financial shortfall created by the coronavirus. “Imagine being unable to write about this. Honestly, that’s another reason this has hit me so hard. I did some journaling but it’s not the same. My city was insane last night and I had to sit quiet.”

It has been a triple whammy for journalists like Hackney, Alcindor and others— covering a pandemic that is killing black and brown bodies at a disproportionately high rate; dealing with the economic fallout from COVID-19; and another cycle of violence that follows and results in more death to black and brown bodies.

“It is getting very difficult to tell the stories of black people dying on an emotional level,” said John Eligon, a national correspondent covering race for The New York Times. “People who look like me or family members of mine, and the practical weight that the police don’t see you as a journalist but as a black man in the street.

“I was walking around in Minneapolis where the protesters were, and these police floodlights came on. I didn’t know if they were pointing guns at us or not because none of us could see. I was holding my phone and press pass out away from my body hoping they wouldn’t think I was holding a weapon but at the same time I need to be reporting what’s going on. It was a very scary moment.”

I asked John if he had ever been to therapy to work out the lingering effects of covering these stories.

“Not for this,” he said. “I don’t know if I have it siloed somewhere in my mind and at some point there will be an explosion. I try decompressing by talking these things out with my wife and unwinding that way.”

It’s a unique balancing act, juggling your humanity with your profession against the backdrop of both being under relentless attack in today’s toxic political environment.

In 2016, when her fiancé proposed to her, Alcindor couldn’t help but think of Sean Bell, the black man New York City police shot and killed ten years earlier on the morning of his wedding.

“My journalism is about emotion and being attached,” Alcindor said. “The moment I cover a story and I don’t think about it nonstop, I need to find another story.”

Still, some topics force her to assume a heavier burden than others. In 2016, when her fiancé proposed to her, she couldn’t help but think of Sean Bell, the black man New York City police shot and killed 10 years earlier on the morning of his wedding. The three detectives charged in the shooting were all acquitted.

“The day he got down on one knee and proposed I started praying he would survive to the wedding day,” she said. “That’s not normal, but that’s what America has become.

“When I saw [Jimenez] getting arrested, my husband was standing in front of the TV with his mouth open. He’s a journalist like me and he couldn’t believe it. It felt very personal … the criminalization of a black journalist. [Jimenez] is an amazing reporter and was very professional, but he didn’t have a choice. In that moment, with all of those officers … it was shocking and scary to watch.”

In these moments, we don’t have a choice. Journalists of color recognize how important, essential, it is that we be there to bear witness. I do not look forward to going back into the streets to hear the cries of a hurting people. In fact, I dread it. But I do it because I recognize the melody. Their song is my song. Their pain is my pain. They have taken to the streets because they feel they have no other choice. So I, and others, follow, because neither do we.

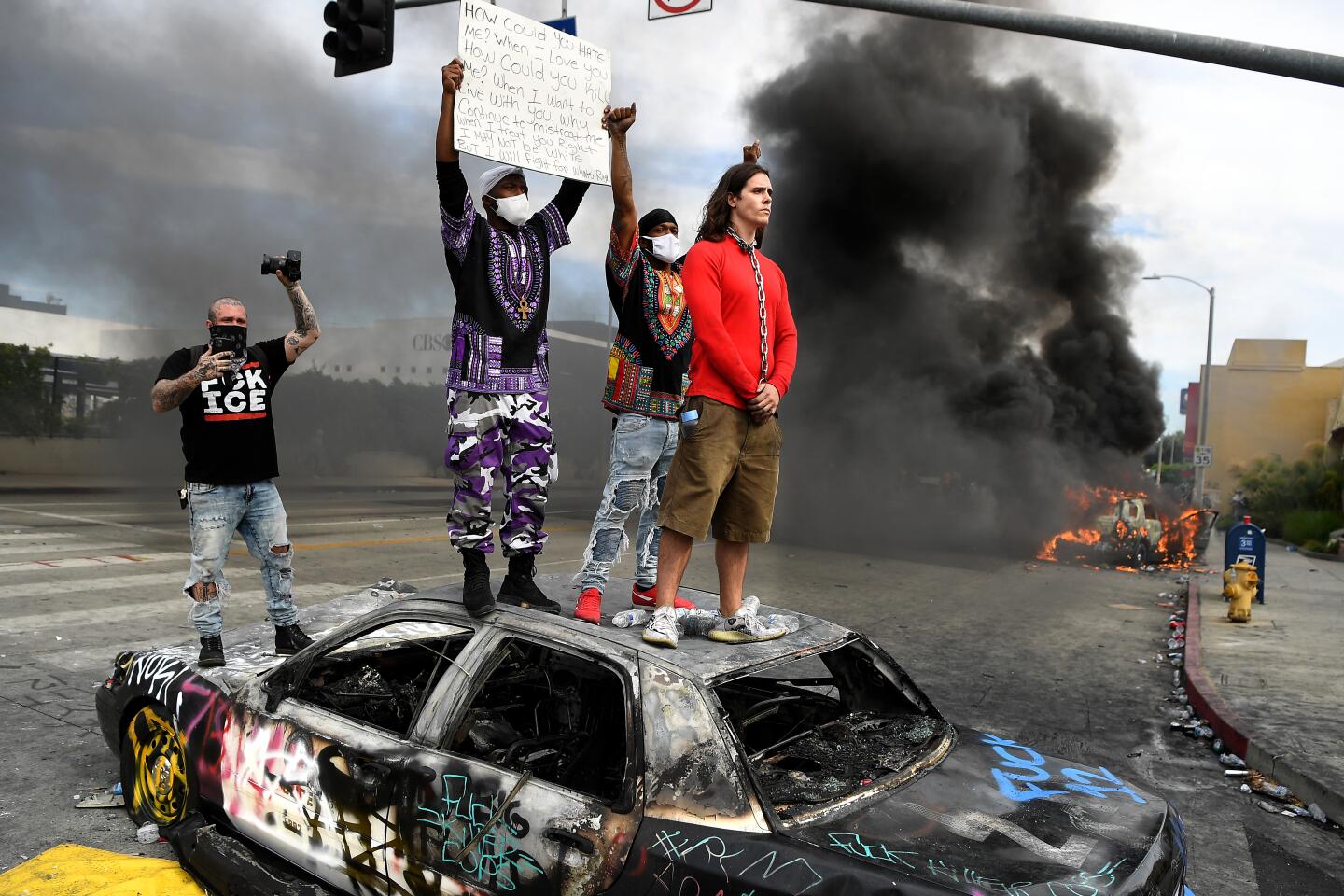

1/81

Protesters stand on top of a burned LAPD cruiser. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

2/81

Protesters stand on top of a bus stop at the Los Angeles Civic Center to demonstrate for justice Wednesday night. (Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times)

3/81

Protestors turn on their cell phone flashlights at Los Angeles City Hall at 9 pm on Wednesday as part of a silent protest against the death of George Floyd. (Gary Coronado/Los Angeles Times)

4/81

A protester confronts National Guardsmen as thousands of protesters march down Spring Street in Los Angeles to demonstrate for justice in the George Floyd murder by cop case Wednesday. (Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times)

5/81

Protesters dance on Spring Street in downtown Los Angeles Wednesday night. (Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times)

6/81

Thousands of protesters march down Spring Street in Los Angeles Wednesday night to demonstrate for justice in the killing of George Floyd. (Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times)

7/81

LAPD Cmdr. Gerald Woodyard takes a knee with protesters and L.A. clergy during a march in downtown Los Angeles on Tuesday. (Kent Nishimura/Los Angeles Times)

8/81

Khalil Mitchell speaks to protesters kneeling near a police line, preaching calm and working to preserve a peaceful protest on Monday. (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

9/81

In Hollywood, hundreds of protesters march Monday against police brutality. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

10/81

AJ Lovelace, a director and writer, and others keep potential looters from entering a dry cleaning store as they attempt to march peacefully. “We need peace and we need someone to talk to each other,” he said after the looters fled the scene. (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

11/81

Demonstrators in Riverside retreat as county sheriff’s deputies fire nonlethal rounds on Monday after law enforcement announced an unlawful assembly. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

12/81

Protesters in Riverside. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

13/81

An arrest in Hollywood during a protest Monday. (Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

14/81

A demonstrator, injured while trying to flee the firing of nonlethal rounds, lies on the ground in Riverside. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

15/81

An LAPD officer arrests a looting suspect in an alley behind a Hollywood Boulevard store. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

16/81

Riverside County deputies advance on demonstrators on Monday. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

17/81

Fireworks thrown by a protester explode at the feet of Riverside police. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

18/81

Riverside County Sheriff Chad Bianco takes a knee with demonstrators. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

19/81

A watch and jewelry store is looted in Van Nuys on Monday. (Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

20/81

A looting arrest in Van Nuys. (Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

21/81

AJ Lovelace, director and writer, tries to stop looters from breaking into a Walgreens in Hollywood. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

22/81

An LAPD officer arrests a suspected looter in an alley behind a Hollywood Boulevard store. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

23/81

Police advance on a line of protesters in Hollywood, firing rubber bullets. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

24/81

Arrests are made of those out after curfew in Hollywood. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

25/81

Protesters in Hollywood. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

26/81

A store is looted in Hollywood. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

27/81

Protesters in Hollywood. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

28/81

People out after curfew are arrested Monday at Sunset Boulevard and Gower Street. (Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

29/81

Arrests in Hollywood. (Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

30/81

Protests in Westwood. (Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

31/81

Volunteers help clean up the mess left by looters in Long Beach. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

32/81

Protest in Hollywood. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

33/81

National Guardsmen outside Santa Monica Place. (Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

34/81

Gilbert Haro and sons Richard, 8, and James, 6, help clean up in Santa Monica. (Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

35/81

Protesters face off with police in Santa Monica on Sunday. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

36/81

Santa Monica stores were the target of looting on Sunday. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

37/81

Suspected looters in custody in Santa Monica on Sunday. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

38/81

L.A. County sheriff’s deputies in Santa Monica on Sunday. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

39/81

Sake House employee Jared Settles can’t bear to watch as the restaurant burns in Santa Monica on Sunday. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

40/81

An arrest in Santa Monica on Sunday. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

41/81

Broken glass from a looted store covers the sidewalk in Santa Monica. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

42/81

Cecelia Rosales, who said she was homeless, walks past a line of police officers in Santa Monica on Sunday. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

43/81

A man guards a convenience store in Santa Monica. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

44/81

Looting erupted Sunday in Long Beach. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

45/81

Police and protesters face off in Santa Monica on Sunday. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

46/81

A police officer inspects the damage to a Santa Monica supermarket. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

47/81

A protester is treated after being struck by a rubber bullet. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

48/81

Looting in Long Beach on Sunday. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

49/81

Looting in Long Beach. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

50/81

A suspected looter in Long Beach. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

51/81

Smashing windows in Santa Monica. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

52/81

An arrest in Santa Monica on Sunday. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

53/81

People walk away with surfboards in Santa Monica on Sunday. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

54/81

People rush out of a looted store in Santa Monica. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

55/81

Protesters in downtown Los Angeles on Sunday. (Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

56/81

Cheers for protesters in downtown Los Angeles. (Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

57/81

City Hall on Sunday. (Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

58/81

A shattered storefront on Melrose Avenue on Sunday. (Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

59/81

Smashed windows on La Cienega Boulevard. (Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

60/81

Downtown L.A. on Sunday. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

61/81

People carry merchandise from a looted store. (Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

62/81

A person carries items from a looted store in the Fairfax District on Saturday. (Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

63/81

A couple of protesters embrace on Fairfax Avenue in Los Angeles Saturday. (Wally Skalij/Los Angeles Times)

64/81

People protest Saturday at Pan Pacific Park. (Kent Nishimura/Los Angeles Times)

65/81

Protesters gather around a fire in the middle of a downtown L.A. street on Friday. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

66/81

Police fire percussion rounds to clear protesters from Grand Avenue in in downtown Los Angeles on Friday. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

67/81

A protester remains defiant after being pushed to the ground by police on Grand Avenue in downtown Los Angeles on Friday. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

68/81

Protesters are arrested by Los Angeles police in front of City Hall on Saturday. (Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

69/81

Protesters block the 110 Freeway. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

70/81

Protesters take to the streets Friday in downtown L.A. (Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

71/81

Protesters are escorted off the northbound 110 Freeway in downtown Los Angeles. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

72/81

A protester is escorted off the northbound 110 Freeway in downtown Los Angeles. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

73/81

Protesters climb over a barrier during the May 29 protest in downtown L.A. (Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

74/81

Protesters block the 110 Freeway northbound and southbound in downtown Los Angeles. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

75/81

Police officers assume a defensive stance as a protester approaches them on the 110 Freeway on May 29. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

76/81

During a May 29 protest, Los Angeles police patrol the 110 after having moved protesters off the freeway. (Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

77/81

A protester rides a skateboard on the 110 Freeway. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

78/81

Protesters block the 110 Freeway northbound and southbound in downtown Los Angeles. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

79/81

A protester confronts LAPD officers on Friday in downtown L.A. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

80/81

A protester lies hurt on the 101 Freeway near downtown Los Angeles on May 27. (Gabriella Angotti-Jones / Los Angeles Times)

81/81

An injured man gets up with the help of emergency workers during a protest May 27 in downtown L.A. (Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)