As parts of Zambia beat back malaria, the nation sets a lofty goal: zero transmissions

- Share via

Wearing blue overalls, green rubber gloves and a helmet while hauling a 22-pound canister of insecticide on her back, Emely Mwale stood inside a small hut and took aim.

“One kwacha, two kwacha, three kwacha,” she counted. The kwacha is the national currency of Zambia, and saying it aloud was her method for dosing out the chemical mist, slowly and evenly.

Mwale, 23, earns $6 a day on the front lines of Zambia’s efforts to eradicate malaria within its borders.

Infections used to be rampant here in the country’s Eastern Province. But residents such as 40-year-old Dailes Phiri — whose 10 children used to contract it routinely, sometimes pushing them to the brink of death — said the spraying has dramatically improved the situation.

“I can’t remember the last time one of the kids got malaria,” she said in the Chewa language through a translator. “Maybe it was five years ago.”

On a continent that has been ravaged by the mosquito-borne disease — and that has been losing ground recently despite expansive internationally funded efforts — the Eastern Province of Zambia stands out for its success.

Between 2010 and 2016, the number of infections here fell 42% from 1.4 million to just under 805,000, and the number of deaths fell 91% from 2,862 to 248. It was here — along with Southern Province, which has seen even bigger improvements — where the government has carried out its most intensive campaigns against the disease.

Now Zambia hopes to replicate those successes nationwide with what experts say is starting to take shape as one of the most comprehensive assaults on malaria in Africa. The effort has a lofty goal: zero new transmissions by 2021.

There is much work to be done. While Zambia, a Texas-sized nation of nearly 16 million people, has seen big drops in malaria deaths, it recorded 6.1 million infections last year. That’s up 36% from 2010 — and part of a trend in Africa that has derailed the World Health Organization from its goal of major reductions in infections and deaths worldwide this decade. Africa accounted for the vast majority of the 216 million malaria cases and 445,000 deaths worldwide last year.

Estimated number of malaria deaths by World Health Organization region

| WHO Region | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO RegionAfrican | 2010 538,000 | 2011 484,000 | 2012 445,000 | 2013 430,000 | 2014 423,000 | 2015 409,000 | 2016 407,000 |

| WHO RegionEastern Mediterranean | 2010 7,200 | 2011 7,100 | 2012 7,700 | 2013 7,800 | 2014 7,800 | 2015 7,600 | 2016 8,200 |

| WHO RegionEuropean | 2010 - | 2011 - | 2012 - | 2013 - | 2014 - | 2015 - | 2016 - |

| WHO RegionAmericas | 2010 830 | 2011 790 | 2012 630 | 2013 620 | 2014 420 | 2015 450 | 2016 650 |

| WHO RegionSoutheast Asia | 2010 41,700 | 2011 34,000 | 2012 29,000 | 2013 22,000 | 2014 25,000 | 2015 26,000 | 2016 27,000 |

| WHO RegionWestern Pacific | 2010 3,800 | 2011 3,300 | 2012 4,000 | 2013 4,300 | 2014 2,900 | 2015 2,600 | 2016 3,300 |

| WHO RegionWorld | 2010 591,000 | 2011 529,000 | 2012 487,000 | 2013 465,000 | 2014 459,000 | 2015 446,000 | 2016 445,000 |

Source: World Health Organization estimates

Zambia’s localized efforts began about a decade ago with a variety of tactics aimed at killing mosquitoes that carry the malaria parasite and transfer it from one victim to the next, preventing people from being bitten and infected and treating them promptly when they do contract the disease.

The campaigns included distributing mosquito nets to cover every bed, increasing the availability of tests to rapidly diagnose infections, mass distribution of anti-malaria drugs, and prophylactic treatment of pregnant women.

The nationwide effort launched last spring is funded with nearly $100 million in international aid, though Zambia has dramatically increased its own spending on malaria — from $1 million in 2010 to $17 million this year.

The campaign is now in full force. Nurses have joined doctors in being authorized to prescribe anti-malaria treatment. Health officials trace people who are infected but who have no symptoms, then test and treat everyone living within 140 meters. Data is shared on mobile phone networks. Spraying programs have increased in intensity and sophistication.

Border checks have been instituted to prevent people with infections from entering the country. At the Kazungula crossing from Botswana, officials use a thermal scanner to take the temperature of each person arriving by ferry across the Zambezi River. A fever triggers an alarm and a malaria test. Those who test positive are sent to a clinic on the Zambia side.

Inside the country, volunteer field workers fan out on foot to distribute information about malaria, lead community education meetings on the importance of spraying, sleeping under nets and removing stagnant water where mosquitoes breed.

Carol Mbewe, 37, a community health worker in Eastern Province, said that in the not-so-distant past, many who fell sick with symptoms of malaria would seek help from traditional healers. Now, if they are stricken with fever they contact her.

One of her colleagues, Adrian Banda, 34, whose territory includes around 1,700 people in 11 villages, said the declining number of cases keeps him motivated.

“It gives me more hope that we can eliminate the disease,” he said.

The government and its supporters insist that is possible by 2021.

“We have the political will,” Chitalu Chilufya, the health minister, told reporters during a recent briefing in the country’s capital, Lusaka.

Success in Eastern Province and Southern Province have fueled a sense of optimism.

“The timeline is ambitious,” said Melanie Luick-Martins, head of health programs in Zambia for the U.S. Agency for International Development, which leads a U.S. malaria initiative launched in 2005 by President George W. Bush. “But the goal is within their reach.”

But other experts pointed to many reasons to be skeptical.

“They’ve made progress throughout the country, I think the government is genuine in its commitment, but I think it is an unrealistic goal to eliminate malaria in the country by 2021,” said Dr. William Moss, a pediatrician at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health who has conducted malaria research in Zambia for several years.

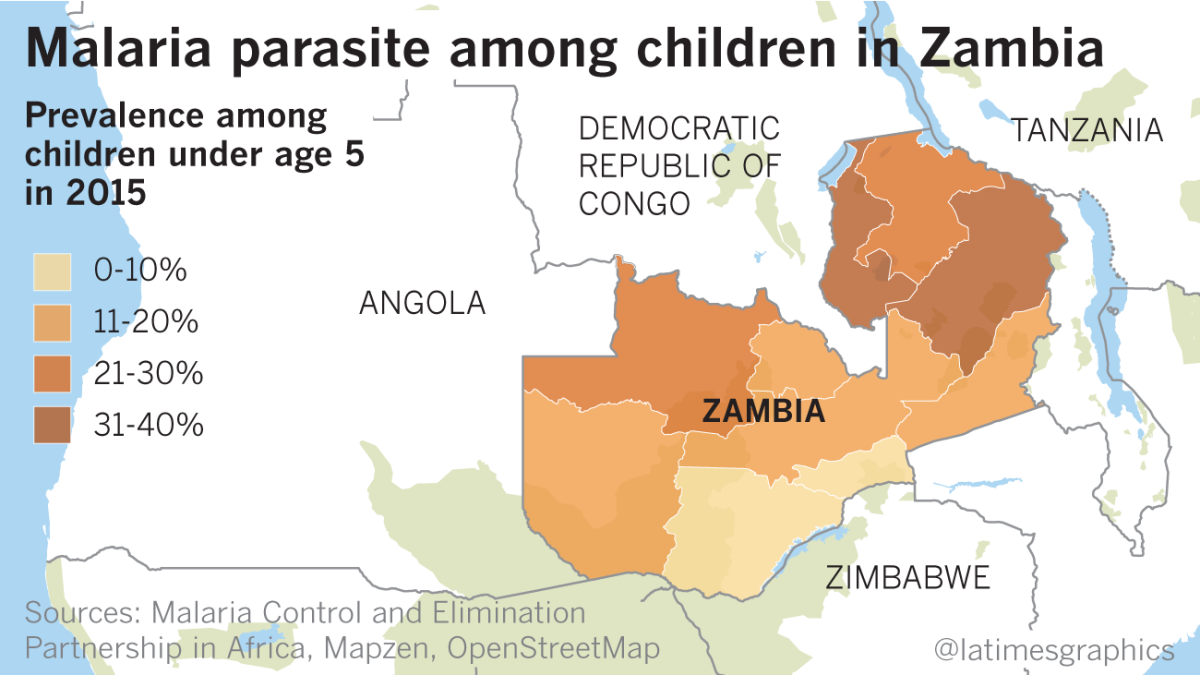

Moss said that while Southern Province has recorded dramatic declines in malaria transmission, other parts of Zambia, such as Luapula Province in the northern region, continue to see “very high and very intense” transmission.

With its lush swamps, the north offers mosquitoes year-round breeding sites.

“The standard package of control efforts … have not had a discernible impact on malaria transmission,” Moss said. “They can’t even control [it].”

Roger Bate, an economist who researches international health policy at the Washington-based American Enterprise Institute, said that because Zambia is landlocked, any malaria-elimination program depends on similar efforts by its neighbors, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, where malaria is especially rampant.

“You could actually achieve elimination and then see malaria come back in a couple of years quite easily,” he said.

Local officials also point to other obstacles.

Resistance to insecticides and anti-malarial medicines is growing. Some residents object to spraying because it forces them to temporarily vacate their homes and sends rats and other vermin scampering through their living space. Malaria tests are rumored to be a trick used to collect blood for witchcraft. Mosquito nets are sometimes refashioned for fishing, wedding dress veils or to hang between soccer goal posts.

Still, fighting malaria has largely become a community project.

One recent night, at a small mud and thatch hut in the Southern Province village of Sikaneka, two men supported the cause by volunteering to be human bait in a research project.

Design Simushu, 31, and Omega Khalama, 27, wore shorts and flip-flops to expose their limbs to mosquitoes at the height of feeding time.

The men used a suction device to catch the mosquitoes that landed on their skin and deposited them in Styrofoam cups while collecting data on the time of each catch and the species of each insect. The bugs are later tested to determine if they are carrying the malaria parasite.

Scientists use all that information to study mosquito behavior — research that helps health officials develop malaria-control strategies.

Using human bait offers the most accurate picture. The men were protected with anti-malaria drugs.

Reporting of this article was sponsored by the Washington Global Health Alliance in partnership with Malaria No More.

For more on global development news, see our Global Development Watch page, and follow me @AMSimmons1 on Twitter.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.