African leaders amp up pressure on the International Criminal Court, with a plan for mass exit

- Share via

Reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa — African leaders have agreed to a plan for a mass withdrawal from the International Criminal Court, amid criticisms its prosecutions focused too heavily on Africans.

But the “strategy for mass withdrawal” agreed on at the African Union summit in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, is not binding, and individual countries can decide whether to leave.

East African countries, particularly Kenya and Uganda, have been campaigning strongly for mass withdrawal, but the court has support among some West African nations.

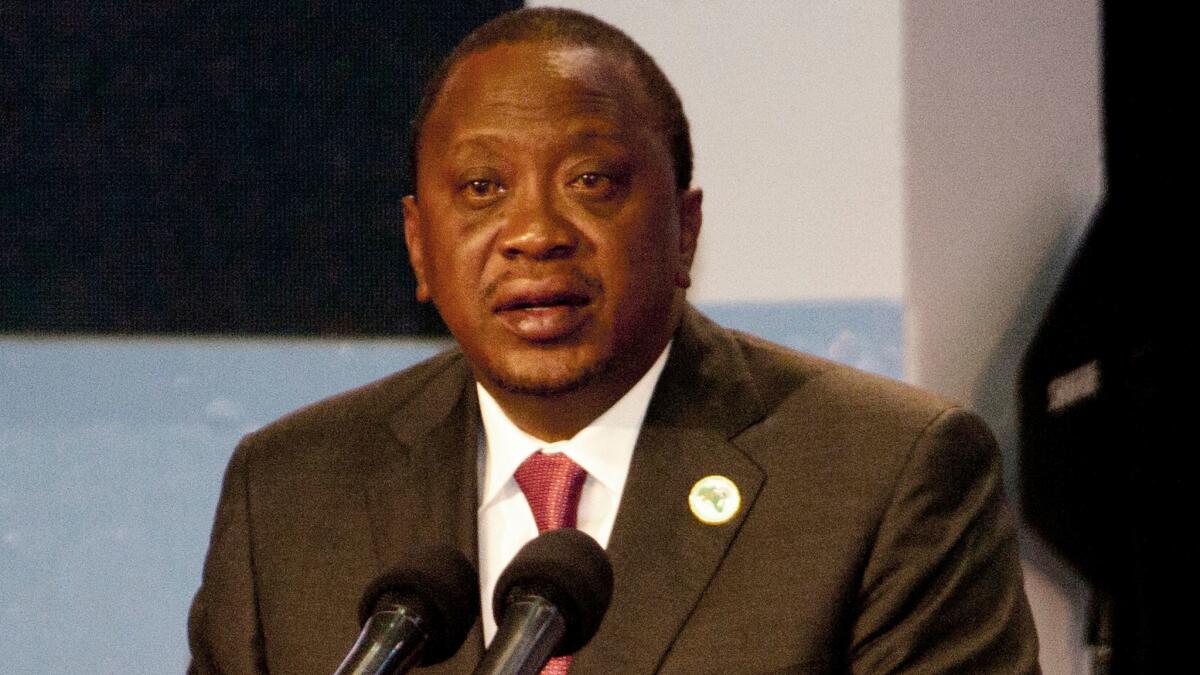

Many African leaders believe the court has unfairly singled out Africa, and question why there has been so little attention focused on other parts of the world where crimes against humanity have taken place. In December, Kenya’s president, Uhuru Kenyatta, said the court was “not impartial,” and was “a tool of global power politics.”

Some African leaders, including Kenyatta, have expressed concern that the court impinges on national sovereignty.

Should multiple African countries pull out, the court’s credibility would be seriously weakened. There has been talk of a pan-African court to carry out the international court’s functions, but such a court would probably offer immunity to sitting presidents, weakening its ability to go after powerful perpetrators of violence.

The move to pull out of the International Criminal Court, or ICC, comes as an era of globalism, optimism and internationalism gives way to more inward-looking populist nationalism, exemplified by the election of President Trump and Britain’s exit from the European Union.

The court has been one of the most ambitious symbols of globalism and international cooperation, but has been embroiled in controversy in recent years after it pursued two sitting African leaders.

The decision by African leaders to stage a mass exit has been some time in coming, with announced departures of South Africa, Burundi and Gambia from the court last year, after criticisms on the continent that the court is biased and anti-African.

Gambia’s new president, Adama Barrow, has said he will reverse Gambia’s departure from the court.

Anti-ICC sentiment in Africa was led by Kenya, after Kenyatta came to power in 2013 with ICC charges of crimes against humanity hanging over his head. The charges were related to his suspected role in inciting postelection violence in disputed elections in 2008. But the court withdrew the charges after the ICC prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, declared that obstruction by Kenyan authorities made it impossible to pursue the case.

The court is seen by supporters and human rights groups as a means to ensure that leaders, military commanders and rebel militias who killed and persecuted people would have no place to hide from international law, and that victims, often powerless and impoverished villagers, would get justice.

South Africa’s elder statesman, Nelson Mandela, who died in 2013, was one of the leading proponents of the court before it came into force in 2002, encouraging African leaders to support it.

The hope was that the court would lead to a new era, end impunity for the world’s worst criminals, and send a chilling message to discourage politicians and armed figures from committing genocide, war crimes and atrocities against civilians and political opponents.

When he signed the Rome Statute founding the court in 1998, Mandela referred to the atrocities that had occurred across Africa as one of his reasons for supporting it.

“Our own continent has suffered enough horrors emanating from the inhumanity of human beings towards human beings. Who knows, many of these might not have occurred, or at least been minimized, had there been an effectively functioning International Criminal Court,” he said at the time, supporting a court with strong independent powers to go after even the most powerful perpetrators.

One of the court’s stumbling blocks, however, was that the U.S., China, Israel, Russia and others either refused to sign, failed to ratify the treaty, or initially signed but later unsigned it.

All but one of the cases opened by the court’s first prosecutor, Luis Moreno Ocampo, were in Africa, most of them at the request of African governments. But later, as the court pursued sitting African leaders, including Sudan’s President Omar Hassan Ahmed Bashir and Kenya’s Kenyatta, African leaders’ opposition to the court hardened and many of them accused the court of pursuing an “imperialist” anti-African agenda.

More recently, the court has opened investigations in other parts of the world, such as Afghanistan.

It was a major blow for the court last year when South Africa announced it would leave. The decision came after the court criticized the government for failing to arrest Bashir when he visited South Africa for an African Union summit. South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeal ruled last year the government acted illegally by failing to make the arrest.

Bashir has been indicted on charges of genocide and war crimes but numerous African signatories to the Rome Statute in Africa have declined to arrest him. Since the court doesn’t have its own police force, it relies on its signatories to enforce its arrest warrants.

South African Justice Minister Michael Masutha called into question this key tenet of the court’s procedures, telling lawmakers Tuesday that the ICC call for South Africa to arrest Bashir undermined the country’s independence and made it difficult to invite foreign leaders to visit.

South Africa is pressing ahead with its withdrawal, in what may become a catalyst for other African nations.

Masutha told the parliamentary committee on justice that “if you indict a sitting president of another country, you are effectively indicting that state itself.”

Twitter: @RobynDixon_LAT

ALSO

In a final insult, Gambia’s ex-leader looted millions of dollars, his successor says

Border walls aren’t unheard of, but today they increasingly divide friends, not enemies

Who’s tracking casualties in Iraq? A California high school teacher

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.