Africans, three Ebola experts call for access to trial drug

Reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa — The president of Liberia called Wednesday for three days of prayer and fasting as “the ultimate solution” to the Ebola virus ravaging West Africa. But many people in Africa and elsewhere called for another potential solution: wider distribution of an experimental drug given only to two American health workers.

As the regional death toll continued to rise, some doctors said it would be immoral to deny the experimental drug to African physicians who contract the virus while treating patients, especially because it was offered to the two Americans, Dr. Kent Brantly and hygienist Nancy Writebol, who contracted Ebola at a Liberian hospital.

The decision to offer them the experimental treatment — while dozens of African doctors and nurses have perished — has provoked outrage, feeding into African perceptions of Western insensitivity and arrogance, with a deep sense of mistrust and betrayal still lingering over the exploitation and abuses of the colonial era.

“It’s very important that our doctors get access to the antiserum,” said professor Alani Sulaimon Akanmu of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, saying it would be scandalous and criminal to deny West African doctors the drug.

He said the drug was an important development that could help reduce the number of Africans dying, in particular the health workers who treated a Liberian, Patrick Sawyer, who flew to Lagos, Nigeria, and died of Ebola. According to Nigerian news reports, Sawyer initially told health workers that he had not come into contact with Ebola, although his sister had died of the disease.

“The young doctor who was caring for him has been discovered to be infected,” Akanmu said. “He’s getting only supportive treatment. We don’t have access to the experimental drug. He’s just waiting. How I wish that the antiserum can be shipped to Nigeria now so that young doctor can be treated.”

In Washington, President Obama said at a news conference that he would need more information about the experimental drug before advocating its wider use.

Some Liberians criticized President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf’s call for three days of prayer and fasting, saying it would only weaken people and make them more susceptible to the virus.

The World Health Organization said Wednesday that it was convening a panel of medical ethicists early next week to consider whether experimental drugs should be more widely released. A two-day WHO crisis meeting over Ebola began in Geneva on Wednesday.

And three leading experts on the Ebola virus said that experimental drugs should be provided to Africa, and that if the deadly virus was rampant in Western countries it would be “highly likely” that authorities would speed access to the medications despite the risks inherent in an untested drug.

“We expect it is a risk we would take if one of us were exposed to Ebola,” the statement from the three researchers said.

The three are Peter Piot, who co-discovered the Ebola virus in 1976 and is director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; David L. Heymann of the Chatham House Center on Global Health Security; and Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust, a British health charity.

“African governments should be allowed to make informed decisions about whether or not to use these products, for example to protect and treat healthcare workers who run especially high risks of infection,” they said, adding that “dire circumstances call for a more robust international response.”

However, Jimmy Whitworth, head of population health at the Wellcome Trust, said only limited amounts of the drug were available. He called for the experimental drug to at least be made available to West African doctors treating Ebola patients.

As for wider distribution, he said, “We simply don’t have enough of the material available.”

One argument mounted by those opposed to offering the drug to Africans is that ordinary patients in a desperate situation might struggle to understand the full implications of the trial of an untested drug. Even so, at some point a testing on Ebola patients — probably Africans, because all outbreaks have been in Africa — will be necessary to determine the drug’s safety.

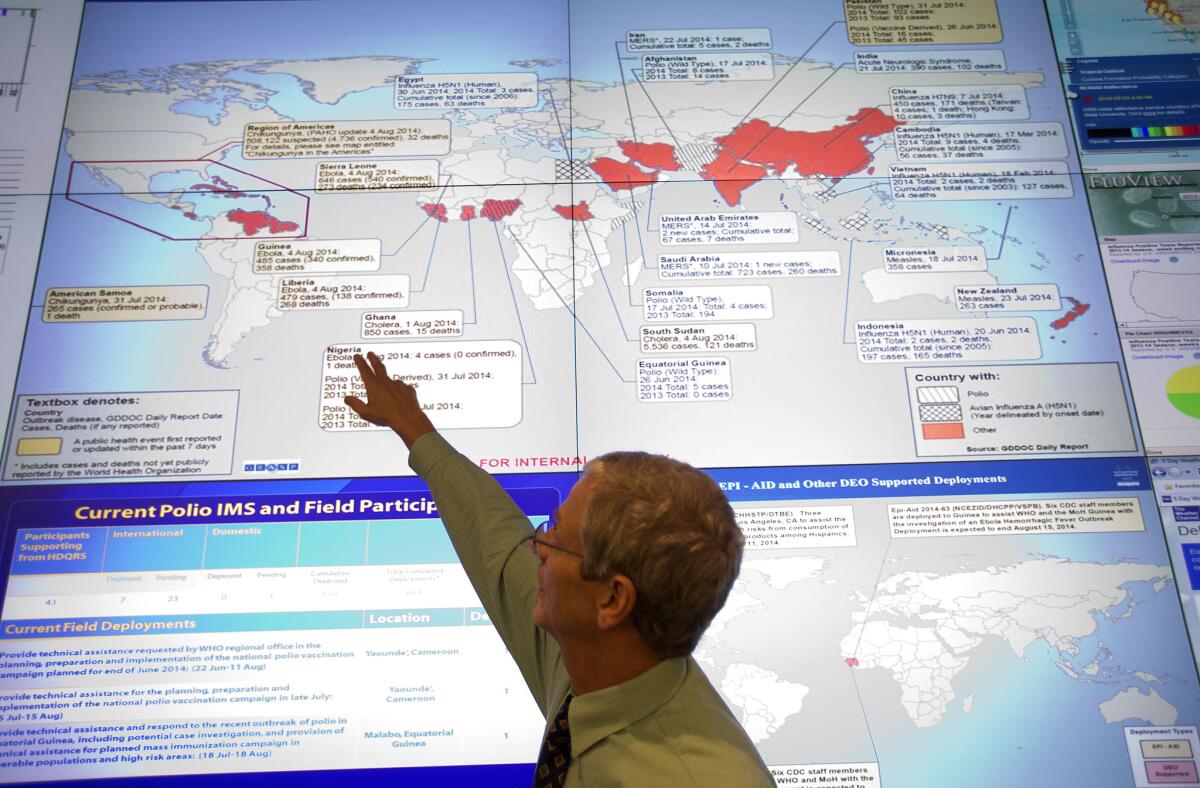

The latest figures, through Monday, show that 1,711 people in West Africa have been diagnosed with the disease and 932 have died, the WHO announced.

The largest number of deaths, 363, have been in Guinea, followed by 286 in Sierra Leone and 282 in Liberia.

A Saudi Arabian man who visited Sierra Leone contracted Ebola and died in a hospital in the city of Jidda, Saudi authorities confirmed Tuesday.

Nigerian authorities Wednesday announced five new Ebola cases, for a total of seven, and two deaths.

In the United States, an unidentified man who was hospitalized in New York with Ebola-like symptoms after returning from a trip to West Africa tested negative for the disease, hospital officials said.

The two Americans who have been confirmed with the virus, Writebol, 59, and Brantly, 33, remained hospitalized at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta after being flown to the U.S. separately on a specially equipped aircraft.

A hospital representative would not confirm their conditions Wednesday, citing patient privacy, but Writebol’s son released a statement saying his mother was tired “but continues to fight the virus and strengthen her faith in her Redeemer, Jesus.”

The WHO said the treatment of the two Americans “has raised questions about whether medicine that has never been tested and shown to be safe in people should be used in the outbreak and, given the extremely limited amount of medicine available, if it is used, who should receive

it.”

“We are in an unusual situation in this outbreak,” Dr. Marie-Paule Kieny, the WHO’s assistant director-general, said in a statement on the organization website. “We have a disease with a high fatality rate without any proven treatment or vaccine. We need to ask the medical ethicists to give us guidance on what the responsible thing to do is.”

On Twitter, some Africans were critical of the decision to provide the drug, untested on humans, to Brantly and Writebol but not to Africans.

“Americans are just wicked and selfish. Secret serum shows up as soon as two of their people get it. What is humanity?” tweeted Uwani Aliyu, who described herself as a makeup artist from Abuja, Nigeria.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.