China’s Xi Jinping is on the cusp of gaining power unseen since Mao Tse-tung

- Share via

Chinese President

Xi and his Communist Party cadres are reinforcing their ideological rigor ahead of China’s most important political event: the twice-a-decade party congress, scheduled to begin Oct. 18.

It’s a giant power struggle among the nation’s elite, with twists that topple careers. This year carries even more weight because the event is expected to replace about half the country’s top leadership and reveal the true extent of Xi’s influence — potentially endowing him with a status akin to that of Mao Tse-tung, the founder of the People’s Republic.

“What we haven’t seen in the post-Mao era is such a clear consolidation of power by one figure,” said Trey McArver, co-founder of Trivium China, a Beijing research firm. “It just feels to everybody this is the Xi Jinping show now. Whatever he wants he gets.”

Top leaders appointed Xi five years ago at the 18th party congress, and the upcoming one the halfway point of his decade-long tenure. Analysts say Xi’s penchant for control — he holds at least a dozen oversight positions — signals he might seek to stay in power and expand his vision of a resurgent China.

Xi launched his presidency with a visit to the National Museum’s modern Chinese history exhibit, where he pledged a “great renewal of the Chinese nation.”

He has sought to do so by weaving the party ever more deeply into society, from corporations to religion. His anti-corruption campaign helped reduce officials’ extravagances such as mistresses and Ferraris and was heralded as lifesaving shock treatment for a toxic societal cancer. It also sidelined his challengers.

And he’s projected a more assertive global role for China, including an international development institution modeled after the World Bank and expansive territorial claims in the South China Sea.

“Xi’s experience, commitment, determination and ability to govern and lead have become something of a rarity on the global political stage,” the official New China News Agency affirmed in an editorial.

Already leader of the party, government and military, Xi received another title in October 2016 when officials elevated him to “core leader.” The label, while symbolic, gives him added stature. His predecessor,

The fact that Xi has assumed dominant control over the propaganda machinery says a lot.

— Willy Lam, a leading China expert at the Chinese University of Hong Kong

Next month’s congress will determine whether Xi’s ideas become enshrined in the party orthodoxy under his name, like Mao Tse-tung Thought or Deng Xiaoping Theory. Only those two leaders reached that level of power.

This conclave will play out in closed-door meetings that determine the next party leaders and policies that will shape everything from China’s banking system to its tactics in dealing with President Trump.

And yet North Korea’s recent nuclear test, which Pyongyang claimed involved a hydrogen bomb, threatens to upstage the meetings. The Communist Party always seeks to avoid any incidents in the run-up to the congress that could trigger surprises or suggest Xi lacks control. China's belligerent ally has the potential to do both.

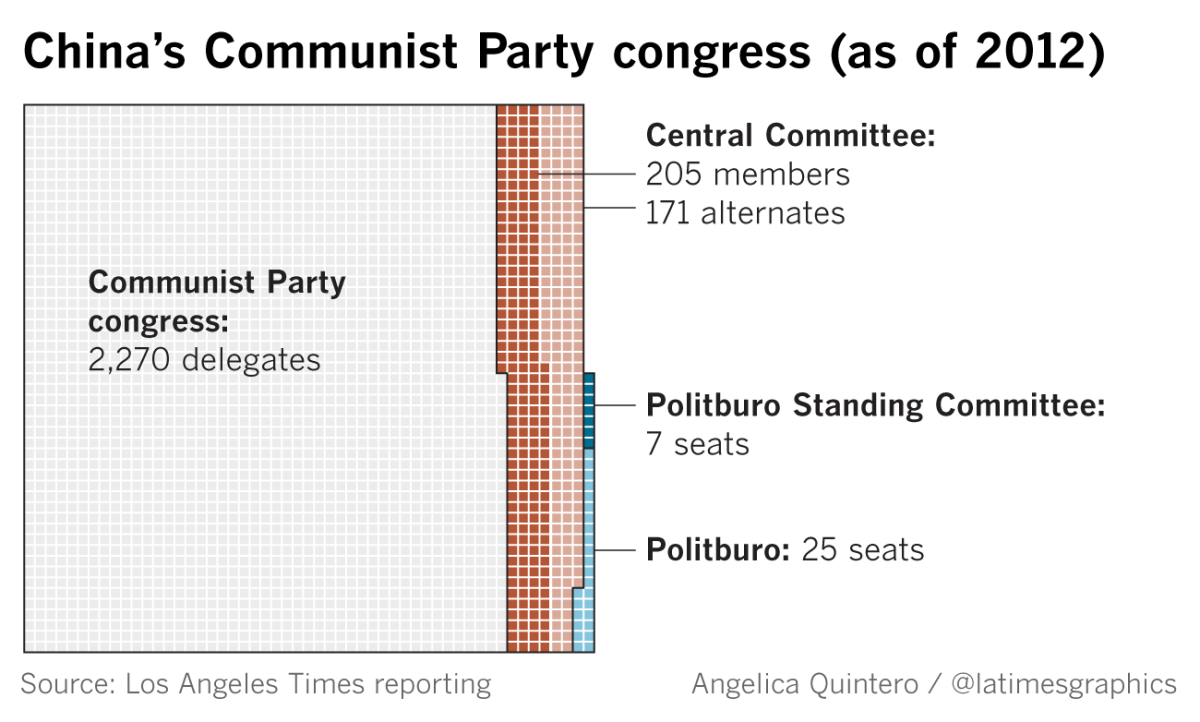

The entire event is cloaked in secrecy. About 2,300 delegates — military generals, heads of state-run chemical companies, village leaders — will applaud decisions hashed out earlier by party chiefs.

It also sets up a crucial five-year period before the 100th anniversary of the party’s first gathering, when a cluster of revolutionaries met inside a small building near Shanghai’s French Concession. The party, whose numbers are dwindling, is determined to survive.

China’ state media are doing their part with unrestrained, unrelenting praise across platforms and in multiple languages.

China Daily, the official English-language newspaper, offered readers the chance to win a Kindle by answering questions about the biggest advancements under Xi.

“What has impressed you the most?” it asked. “The record-setting bridges and tunnels, the convenience of mobile payments, or the scientific achievements?”

A new documentary broadcast on state-run television extols his ideas. It’s 10 episodes long.

Meanwhile, China’s broadcast regulator has temporarily banned TV stations from airing dramas during prime time that contain sensitive material or are “too entertaining.” Internet monitors have shut down more than 3,000 sites for showing violence, porn or threatening national security. The government is reportedly taking steps to block an online tool used to breach China’s “Great Firewall.”

These recent actions highlight party control, but they also foreshadow how Xi plans to rule. Cambridge University Press, the world’s oldest publishing house, recently complied with Beijing’s request to remove hundreds of articles from the Chinese website of a leading academic journal, China Quarterly. These included descriptions of the Tiananmen Square protests and analysis of the Cultural Revolution. The organization reversed its decision in late August after academics decried the move.

“The fact that Xi has assumed dominant control over the propaganda machinery says a lot,” said Willy Lam, who studies the country’s elite politics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “Most likely, Xi wants to stay in power.”

Some look for clues in the hilly southern metropolis of Chongqing.

Just before the last congress, the city’s telegenic party secretary was kicked out for “disciplinary violations” and his wife was convicted of murdering a British businessman. Once destined for a top party position,

Sun Zhengcai, his successor, also looked set to assume a top party post this fall. Then, in July, he disappeared. Officials have since put him under investigation for violation of party rules. The one-time presidential contender was replaced by a Xi ally.

Sun’s dismissal suggests Xi desires a different succession strategy than the approach of previous leaders, said Zhang Lifan, a prominent party historian in Beijing.

“He basically broke the rules,” he said. “He doesn’t want his successor to be determined by someone else.”

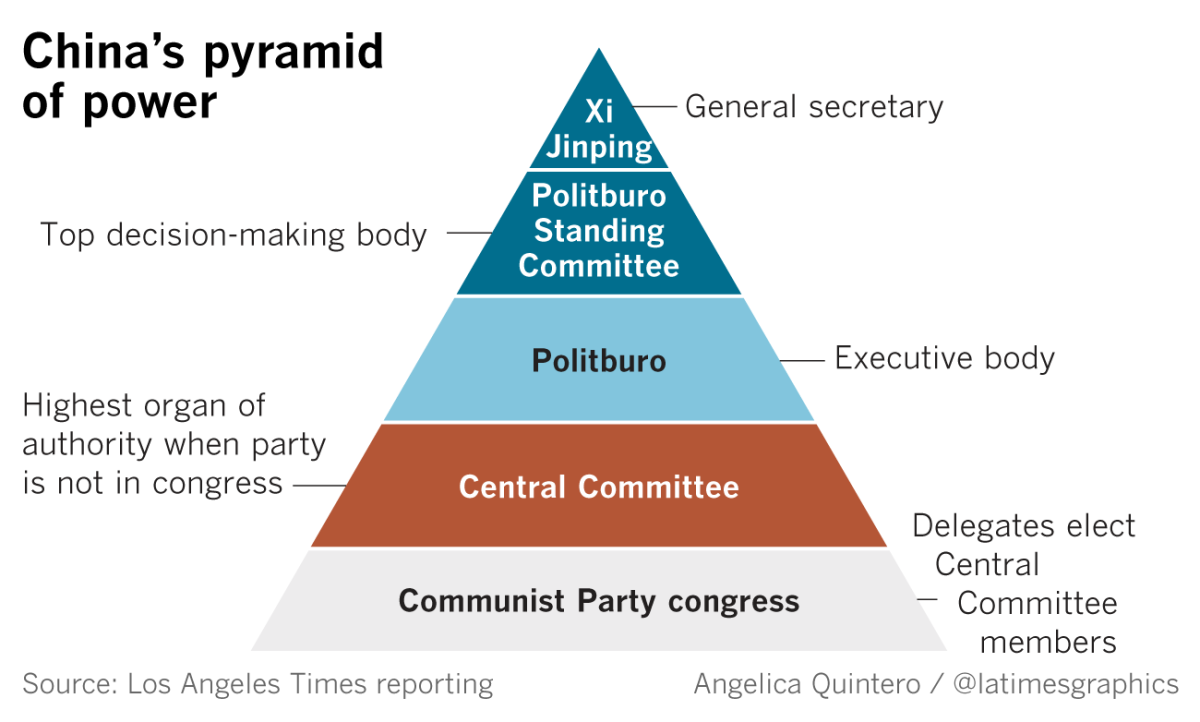

The party will replace up to five of seven members on its Politburo Standing Committee, the top decision-making body -- unless Xi bends retirement norms. The chosen males walk on stage at its conclusion in nearly matching black suits, a dramatic unveiling of the next generation of leaders.

Experts are watching whether a successor will appear at all. They’re also eyeing the fate of Wang Qishan, 69, a Xi associate and head of his anti-graft campaign. If Wang doesn’t step down, it may indicate Xi has abandoned traditional retirement practices so he can score a third term.

The Congress showcases the strength of Communist Party governance, so officials spend months proving their loyalty and warding off drama. China just announced a raft of new financial regulations, including curbs on overseas investments in sports and entertainment to ensure money doesn’t pour out of the country and threaten economic stability.

Even booze is a casualty. Guizhou province, home to Moutai, the country’s most famous brand of baijiu, a potent liquor, recently banned government employees from drinking alcohol at official events.

The party congress, at some level, affects everyone.

“My life is certainly getting less convenient,” said Chen Xuan, 29, a sales consultant who complained of increased security checks on Beijing’s subway.

Chen, headed to work downtown, reckoned he could handle the frustration. “I hope we all have a better future in five years,” he said.

Red banners fluttered in the wind nearby, praising Xi and the party.

Nicole Liu and Gaochao Zhang in The Times’ Beijing bureau contributed to this report.

Meyers is a special correspondent.

Twitter: @jessicameyers

ALSO

China's Belt and Road Forum lays groundwork for a new global order

To understand China's President Xi Jinping, don't look to Mao Tse-tung, look to Chiang Kai-shek

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.