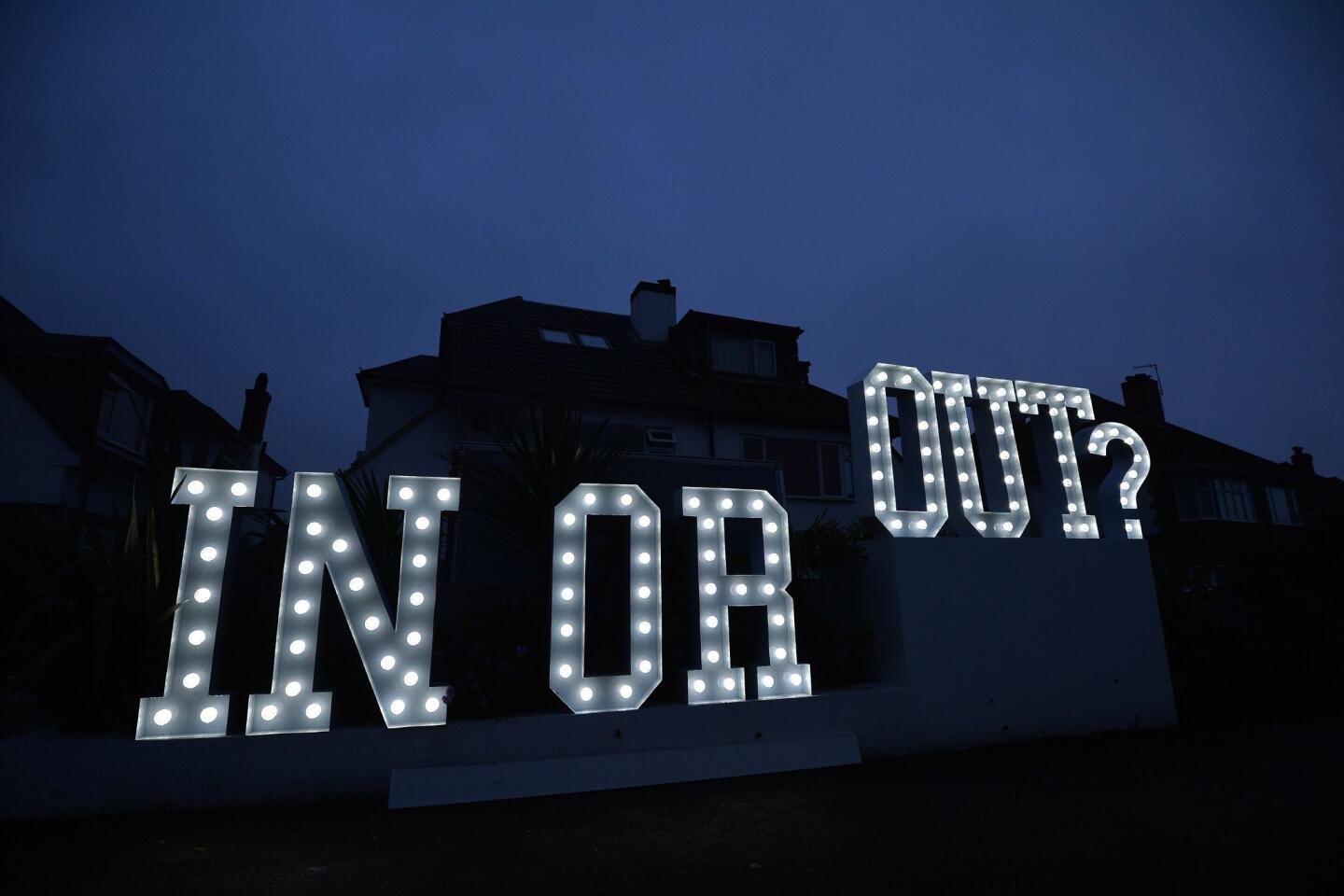

Confused? We break down the ‘Brexit’ vote for you

Britons voted Thursday to leave the 28-nation European Union, a historic vote that sent shock waves across the continent.

- Share via

Reporting from Paris — It was a contentious campaign, and in the end, a stunning outcome. Britain voted to leave the European Union on Thursday, by a 51.9% to 48.1% margin.

What happens next, and what does it mean for Britain, which has been a key member of the EU, an organization created after World War II to generate economic cooperation and avoid war?

What were the main points of contention?

The campaign covered many issues, including widespread disillusionment with EU regulations by those who wanted to leave. But it ended up focusing on sovereignty and immigration. “Brexit” campaigners — Britons who favor exiting the union — claimed their that country was being ruled by faceless bureaucrats in Brussels and that the free movement of Europeans to live and work across the 28 EU member states had led to an influx of migrants. Britons who favored remaining in the EU countered that only about 13% of British acts of parliament and statues were to implement EU laws and many EU regulations do not affect the United Kingdom. Moreover, they maintain that immigrants contribute more in taxes than they cost in welfare or public services and have brought Britain the fourth lowest unemployment rate in the EU, at just 5%.

Updates: Britain votes to leave European Union »

Who wanted to remain, and who wanted to leave?

The outcome reflected deep social, economic and generational divisions in Britain between those who have benefited most from being part of the EU and those who perceive they haven’t. The business class, intelligentsia and many politicians — including the majority of the 650 members of Parliament — favored remaining in Europe. London, a city with an international flavor whose economy has boomed thanks to ties to Europe, voted 60% to 40% to stay. Scotland voted strongly to remain, as well, as it has benefited from EU programs. But most other parts of England that are economically weaker voted to leave. Around 58% of voters older than 65 wanted to leave, while 75% of those younger than 24 voted to remain.

What does the vote mean for Britain?

Technically, it will be up to two years before Britain officially exits the EU, so membership and all that comes with it doesn’t change right away. But political and financial repercussions were felt immediately. British Prime Minister David Cameron, who called the referendum and supported Britain’s remaining in Europe, resigned. The ruling Conservative Party now must choose another leader. The British currency, the pound, plummeted to its lowest level against the dollar since 1985, and shares dropped on European and Asian financial markets over worries that Brexit could weaken trade and add uncertainty at a time when economies worldwide already are struggling. The ratings agency Standard and Poor’s removed Britain’s AAA economic rating, meaning it will have to pay higher borrowing costs, because it could slow the nation’s economy.

How might the vote affect the makeup of the United Kingdom and Europe?

Scottish leaders suggested they could push for another referendum on the country’s independence from Britain, just two years after Scots voted in September 2014 to remain in the U.K. Leaving Britain might be a way for Scotland to stay in the EU. In Ireland, there were calls for Northern Ireland to join the Irish Republic, an EU member state, to create a reunited island, though that would be contentious because many Northern Irish Protestants oppose becoming part of Ireland. More broadly, the successful “Leave” campaign in Britain might encourage strong Euro-skeptic movements in other EU member states, including France, Italy and Denmark. After the Brexit victory, France’s far-right Front National demanded a similar referendum in France. So the big question is whether Britain’s vote might lead to the dismantlement of the EU, or even a reversal of the steady move toward more political union.

What happens next?

No one knows for sure, as this is the first time a country has decided to leave the European Union. But the withdrawal almost certainly will be prolonged and divisive, with recriminations internally in Britain and between British and European political leaders. The next British prime minister — whomever it may be — must evoke Article 50 of the 2009 Lisbon Treaty, which sets in motion the process of withdrawing from the EU. Cameron has said he will leave this to his successor. The favorite is Boris Johnson, a Conservative member of Parliament who once was a Europhile but helped lead the campaign to leave the EU. The terms of Britain’s leaving have to be negotiated with the remaining EU member states, and the issues will be complicated. Under Article 50, negotiations should be finalized within two years.

Specifically, what needs to be negotiated?

Britain will try to maintain access to the European trade market on similar terms as other member states — which means the free flow of goods and services. But France and Germany have warned that the U.K. cannot leave and retain the advantages of membership. Adding to the complexity, the European Parliament can veto any agreements between the EU and Britain. And the British parliament will have to rescind the European Communities Act, which gives EU law primacy in the U.K. Britain has to extricate itself from various EU agreements, running to 80,000 pages, that will need to be repealed, amended or kept by the British Parliament. If there is no agreement at the end of two years of negotiations with the EU, the U.K. will be subject to World Trade Organization rules, which means trade tariffs on all goods sold to the EU. Though WTO tariffs generally have fallen substantially over the years, business still will see them as a burden.

How will this affect the daily lives of Britons and Europeans living in the U.K.?

Britons living in European countries at some point could find themselves in limbo over whether they will have a reciprocal healthcare provision, which generally is free from national health services in Europe; the right to travel and live in EU countries without visas and permits; and when they will need to join the “Non-EU” immigration queues at airports and stations. Similarly, many Europeans who are free to work and live in Britain may find obstacles to remaining.

Can Britain change its mind?

Referendums are not legally binding in Britain, so Parliament could ignore the result of the vote. As a practical matter, that is considered unlikely, though one possibility is that a general election could be called with the main issue being whether the newly elected Parliament should reconsider the decision. But those who voted to exit Europe would fiercely oppose this.

If Britain does leave the EU, could it rejoin?

Not easily. There is no way back into the European Union unless there is unanimous agreement from all other member states, many of whom will be angry at Britain’s departure and most likely unwilling to let the country back in.

Willsher is a special correspondent.

MORE ON ‘BREXIT’

What was the breakdown in ‘Brexit’ votes?

‘Brexit’ shock waves rock Germany and the rest of Europe

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.