Airtime for Israel’s Arabs

NAZARETH, ISRAEL — Maram frets that she’s fat. Tony says men don’t care how they look. Shahd thinks nose jobs are fine.

It may sound like usual talk-show blather until you consider that the three commentators are preteen children. And something far more unusual for Israeli television: They are Arabs.

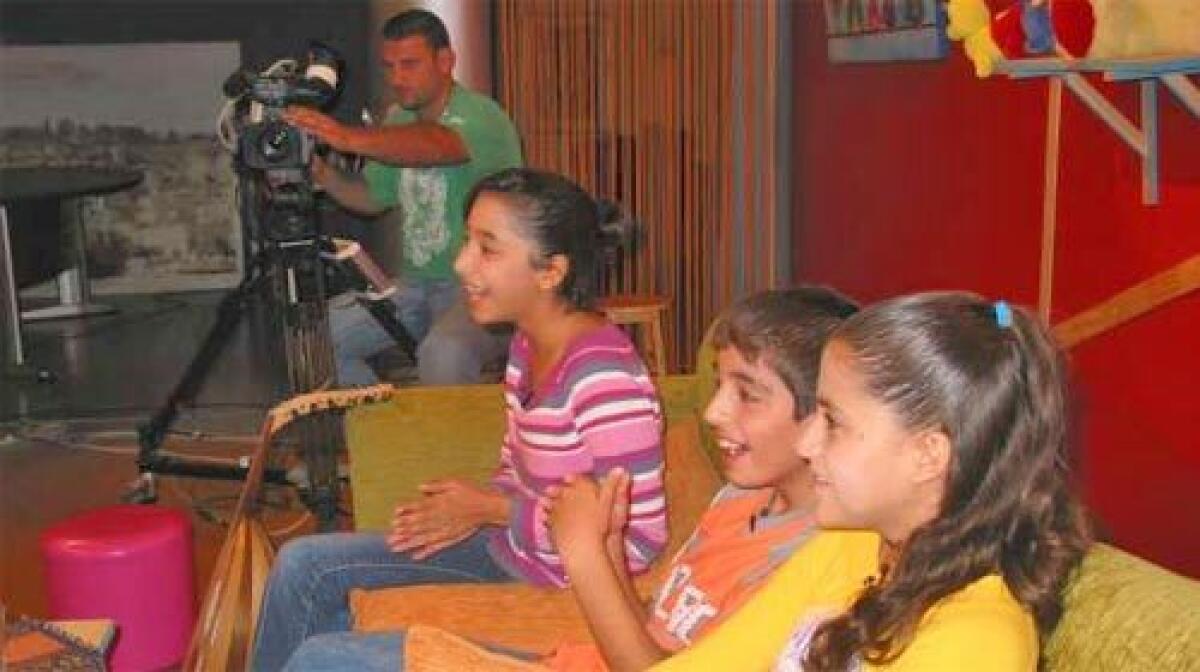

Every week, Maram abu Ahmad, 12; Tony Khleif, 11; and Shahd Shahbari, also 11, get together on camera with an adult host to discuss, in Arabic, their lives and views during freewheeling chats that regularly veer into the minefields of politics and identity.

The children have aired opinions on religion, their relations with Israel’s majority Jews and the ever-tricky issue of being Arabs who are citizens of the Jewish state. (Maram got in trouble with her mother by saying on air that she considered herself Israeli, not Palestinian.)

They also have discussed homosexuality, Iran and the United States. The children hammered President Bush for the Iraq war -- Tony declared him a “dictator” -- but they praised the United States for pretty landscapes, hamburgers and hip-hop. A recent taping focused on beauty and image, at one point delving into what physical characteristics Arabs prefer. (All three said blond hair and blue eyes.)

“I want everyone to hear my thoughts,” Maram, with lively brown eyes and braces, said before a recent taping. She writes songs in English and dreams of directing animated movies. Maram, who is Muslim, said she wants Jewish viewers “to think that we are smart, that we know how to express our feelings.”

The half-hour program, called “Haki Kibar,” or “Grown-Up Talk,” is part of a new effort by the country’s dominant commercial broadcaster, Channel 2, to put more Arab citizens on the small screen. Arabs make up a fifth of the Israeli population, but they are almost never seen on locally produced television.

Prodded by governmental regulators and by Arab-rights activists who have long complained of discrimination, the broadcaster has hired a full-time diversity director and, in addition to the children’s program, begun to add Arabs to some of its most popular shows, including Israel’s version of “American Idol.”

The children’s talk show, produced by an Arab-run company in the northern city of Nazareth, has aired weekly since late summer, albeit during a daytime slot when viewers are scarce. The program, which carries Hebrew subtitles, also features a separate segment with a trio of 8-year-olds with the same host, comedian Hanna Shammas.

The children sit snug on a couch, clutching pillows and fidgeting as they respond on the spot to improvised questions relayed to Shammas by an editor in the control room.

The studio, painted cherry red and canary yellow, is decorated with stuffed animals to evoke a playroom. But the subject matter is often startlingly grown-up, as when the younger threesome was asked which side was responsible for Israel’s war last year with Hezbollah guerrillas in southern Lebanon. A skinny boy named Fares blamed Israel, but botched the facts by saying the Israelis had kidnapped three soldiers from Lebanon. (The war began after Hezbollah captured two Israeli soldiers from Israeli territory.)

In what may prove a riskier television venture, Keshet Broadcasting, one of the two companies that operate Channel 2, is readying a drama written by Sayed Kashua, a noted satirist, that offers a wry take on the challenges and foibles of an Arab family loosely based on his own. Most of the dialogue will be in Arabic, with Hebrew subtitles. (Hebrew portions will carry Arabic subtitles.)

One subplot will be a budding romance between a Jewish man and an Arab woman -- incendiary stuff for Israeli television. Even the show’s title, “Arab Work,” walks the edge by playing on a Hebrew phrase used to refer to slipshod work.

“It’s a crazy adventure,” said Udi Lion, an observant Jew who as director of special programming at Keshet oversees efforts to get more TV time for Israel’s various underrepresented groups, including Ethiopian and Russian-speaking immigrants and devout Jews. “It can only be a hit or a catastrophe.”

Still, these are baby steps in a land where Arab citizens complain of discrimination and social inequities extending far beyond their role on television. Advocates for Israel’s 1.4 million Arabs say the reforms at Channel 2 are insufficient to reverse decades of media neglect.

Most Arabs in Israel skip local television and instead tune in shows via satellite from Arabic-speaking countries, such as Syria and Egypt, said Jafar Farah, director of the Mossawa Center, a Haifa-based advocacy group for Arabs in Israel.

The result is that ordinary Jews and Arabs, who don’t talk to each other much in daily life anymore, are increasingly alienated from each other on television, he said.

“Jews don’t see Arabs in media, and Arabs don’t watch Israeli media,” Farah said.

Few in Israeli television disagree with that assessment. Studies by private groups and the governmental agency that oversees the nation’s two commercial television stations, Channels 2 and 10, have found an almost complete absence of Arabs on Israeli shows. Most of the time, a recent study found, Arabs are presented in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and thus in a threatening manner. A few Arab lawmakers are featured regularly to criticize Israel’s policies, bringing them frequently into Israeli living rooms but gaining little affection for Arabs among Jewish viewers.

Israelis are unlikely to see ordinary Arabs talking about healthcare or raising children, said Dror Sternschuss, a former advertising executive who is chairman of Agenda, the Israeli group that did the study.

“If we want the Israeli Arabs to be and feel part of the Israeli community, they should see themselves on TV,” said Sternschuss, who is Jewish. “If we want our children to have the ability to understand and live together with Arabs, they have to see them on TV.”

Israeli regulators in recent years have imposed content quotas aimed at forcing broadcasters to air Arabs and other minorities more often, part of a wider effort to show a fuller picture of Israeli society.

The Mossawa Center went to court in 2003 to demand more Arabic- language productions and an increase in the number of Arab employees at the two commercial TV stations. In response to this and its own findings of neglect by television stations, the authority that oversees Channel 2 imposed as a requirement of the broadcaster’s sale in 2005 that it commit at least 60 hours of airtime yearly to “peripheral” segments of the Israeli population. Regulators hope to make similar restrictions part of the operating rules for Channel 10 when it next comes up for bid in 2012.

That quota represents a tiny share of the total broadcast time. But perhaps more significant are the groundbreaking ways that Channel 2 is integrating Arabs into its programming. It has begun featuring them in popular prime-time shows, noted Ayelet Metzger, deputy director-general in charge of television at the Israeli agency responsible for the commercial stations.

At the urging of Keshet’s Lion, the broadcaster wrote Arab families into two reality-type shows, “Wife Swap” and “Supernanny.” The “Wife Swap” episode with the Arab family was the series’ highest rated of the season. In that episode, the Jewish wife was treated warmly by an Arab family she went to live with, while the transplanted Arab wife and Jewish husband sniped at each other, which produced a wave of Internet chatter castigating the man’s behavior toward her.

“This was a tremendous breakthrough,” Metzger said. “A lot of this is happening because of what the regulation instructed.”

This year, Arab singer Miriam Tukan drew a following by singing in Hebrew on “A Star is Born,” a popularity contest modeled after “American Idol.”

Tukan, with waist-length black hair and a lilting delivery that gave the songs an Arabic flavor, was voted off after making it to the pool of 10 finalists, much further than Lion had imagined possible when he first pushed the idea of an Arab contestant to skeptical executives at Keshet.

“I was surprised the Israeli public was mature enough to support her,” Lion said.

He said that experience, along with favorable viewer response to a drama that has Russian-immigrant and ultra-Orthodox characters, is proof that offering a broader palette might also make shrewd business sense by helping Israeli television improve ratings.

Lion said Israel lags far behind U.S. television when it comes to diversity, even when compared with the age when blacks held only secondary roles.

“Until ‘[The] Cosby [Show]’ came, and suddenly there was a doctor and in the program there could be adult black Americans -- we are behind that,” he said.

Skeptics say Lion means well, but that the steps taken by Channel 2 are not ambitious enough to begin closing the gap between Jews and Arabs in the Israeli media. Few Arabs work in Israeli news departments, for example, and Lion said his assistant is the broadcaster’s only Arab employee.

Even those who welcome the changes at Channel 2 say its efforts can seem halfhearted. Alarz, the company that produces “Grown-Up Talk,” is paid only $2,000 per half-hour episode, according to company officials, too little even to cover its costs of taping and editing.

The program’s time slot, at 1 p.m. on Fridays, is a ratings wasteland in Israel. Lion and the show’s producers have desperately sought viewers by posting clips on YouTube (one example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= os9zhlZNsbc) and distributing the Web links to friends and anyone else who might want to see them.

Nizar Younes, general manager of Alarz, said the company hoped to sell the program to a broadcaster in the Arab world, such as Al Jazeera. Yet some of the show’s subject matter, acceptable by Israeli standards, may be too racy for more conservative Arab societies.

The children say they hope to project an image of Arabs that is progressive, open-minded and modern. Whether they can change the minds of Jewish Israelis through a little-watched, half-hour show remains to be seen -- they see the limitations but insist on trying.

Jews think that “only they are supposed to be on TV, not us,” Maram said. “If they see our show on Friday, maybe this will change their idea.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.