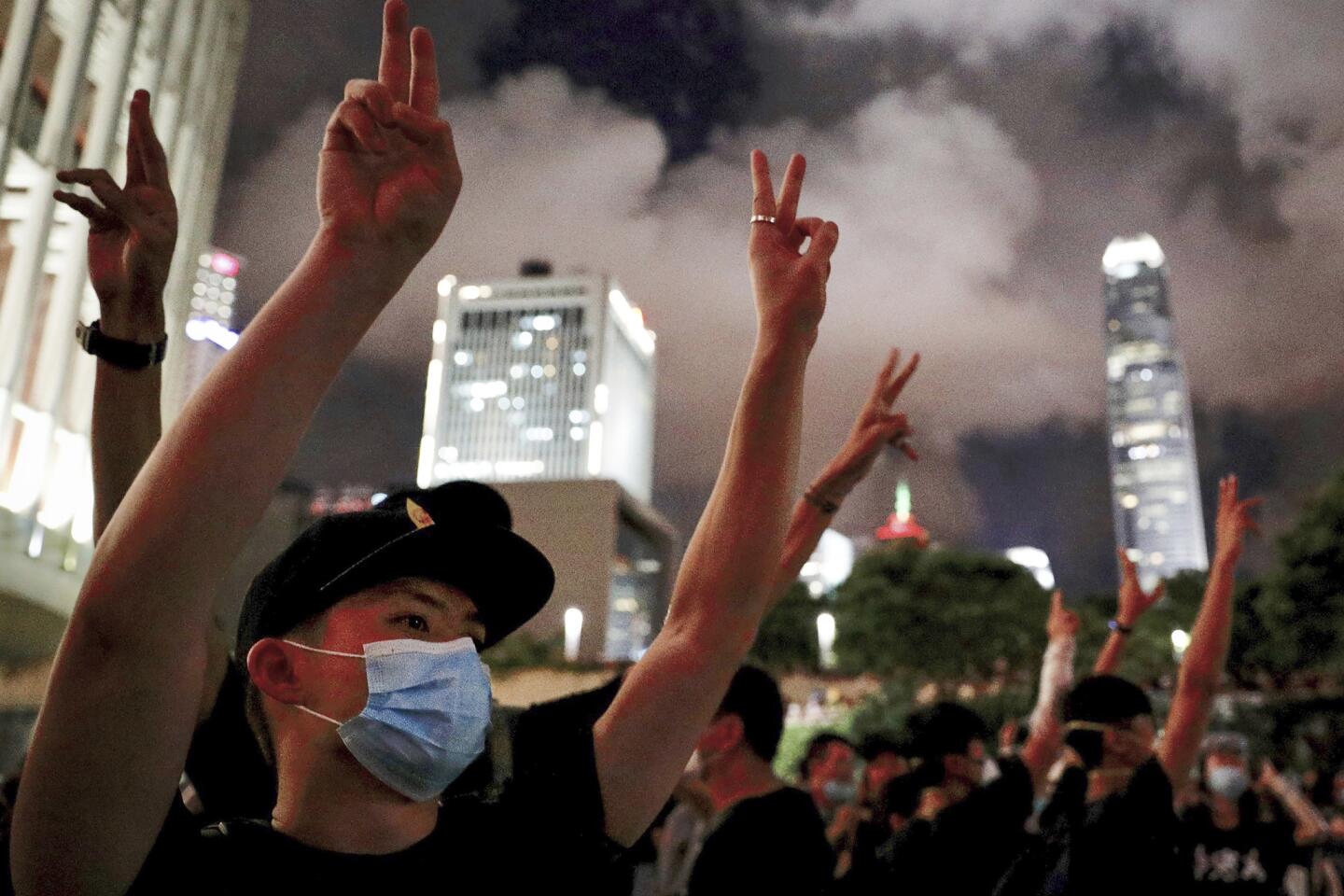

Hong Kong protests escalate as violent demonstrators overrun legislature building

- Share via

Reporting from Hong Kong — Protests in Hong Kong turned violent Monday when demonstrators stormed a legislative building, smashing its glass walls, dismantling fences and gates and vandalizing the inner chamber. It was a striking turn in what had been a largely nonviolent movement and raised questions about how much further dissent the mainland Chinese government will tolerate.

The demonstrators tore down portraits of legislative leaders and spray-painted pro-democracy slogans on the walls of the main chamber. They also raised a sign that read: “There are no violent rioters, only a violent regime.”

On this day, the anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover from Britain to China, hundreds of thousands tried to keep the protest peaceful, marching through the streets in an echo of two previous marches against an extradition bill that many believe reflects Beijing’s growing control over Hong Kong.

But some protesters had other ideas.

Agnes, Shing and their son Alex stared at a television screen in disbelief as protesters charged the legislative building.

The family had come to Causeway Bay to join a third peaceful march against the extradition bill. They were standing at an electronics shop next to the road among growing crowds before the march began. But its planned ending point seemed to already be in chaos.

“A lot of Hong Kong people are very peaceful. They don’t want to see this kind of violence,” said Agnes, 45, who declined to give their family’s last name for privacy reasons. “We feel very heartbroken to see these teenagers.”

July 1 is Establishment Day in Hong Kong, an official holiday meant for celebrating the territory’s handover in 1997 from British to Chinese rule. But it’s also a protest day for civil society and pro-democracy groups, with particular momentum this year from growing public anger against the extradition bill.

Hong Kong’s government has suspended the bill, but protesters are demanding total withdrawal to ensure it isn’t reintroduced. In addition to an independent investigation of both police and protester violence over the last few weeks, many also want Chief Executive Carrie Lam to take responsibility for ongoing unrest, or to step down altogether.

Monday’s protesters split into two groups: One comprising hundreds of thousands who marched peacefully and the other consisting of those who besieged and then stormed the legislative building, using metal bars and trolleys to smash its glass walls, pushing aside legislators attempting to de-escalate the situation. The protesters also dismantled a fence around the building and raised a black version of the Hong Kong flag, featuring a bloodied, withering flower at its center.

“If we burn, you burn with us,” read a red banner hung over one side of the legislative building.

Lam held a news conference at 4 a.m. Tuesday condemning the “extreme use of violence and vandalism by protesters who stormed into the Legislative Council building” while affirming the march as reflective of Hong Kong’s “core values” of peace and order.

“Nothing is more important than the rule of law in Hong Kong,” Lam said, adding that the government had responded to protests against an extradition bill by suspending the bill.

Protesters’ other demands — such as releasing demonstrators arrested without an investigation — would violate the rule of law, Lam said.

Police Commissioner Stephen Lo defended the police as having been under siege for nearly eight hours without responding to the protesters.

Secretary for Security John Lee read out potential charges for the protesters arrested, including breaking and entering and possession of weapons.

The Civil Human Rights Front and pan-democratic legislators released a joint statement saying legislators had requested to meet with Lam on Monday, only to be rejected.

“We cannot be angrier at her rejection to the request, which proves her ‘willingness to listen’ to be the ugliest political lie. Lam’s arrogance revealed by her public responses since June 9 have only poured fuel [onto] the flame, and [led] to the crisis today. Lam is the culprit,” the statement read.

Just after 10 p.m., police announced on Facebook that they were planning to clear the legislative building and would use “appropriate force in the event of obstruction and resistance.”

Inside the chamber, protester Brian Leung climbed onto a table and removed his mask, calling on protesters to stay.

“We’ve come too far. This is our final chance. We can’t afford to lose,” he said, asking protesters to either stay inside or surround the building, in hopes that larger numbers of demonstrators would deter the police.

Outside, some protesters left while others continued to pass supplies and barriers into the building through assembly lines.

At 11 p.m., multiple protesters’ groups made different statements. One group stood at the front of the chamber, asking to meet with Lam and reiterating five demands: withdrawing the extradition bill, revoking the classification of protests as riots, dropping all charges against all extradition bill protesters, investigating police violence, and instating universal suffrage in 2020.

Some groups on the messaging app Telegram shared another statement they called the “Admiralty Declaration,” calling for classification of recent protests as “democratic movements instead of riots.”

“On behalf of all HKers, we shall never cease pursuing universal values and rule of law,” the statement read. “HKers can no longer stand the injustice that is our government. We shall raise our shields and arms to overthrow the puppet Legislative Council and the Government.”

As midnight approached, most protesters exited the building after a tearful debate over whether to stay or go. A handful remained, one of whom told local media that his father had fled the Cultural Revolution in China to Hong Kong for his sake. Now he wanted to take a stand for his own kids, he said.

Hundreds of armored riot police officers bearing shields and batons, backed up by dozens of police vans flashing sirens, marched toward the legislative building at midnight. They surrounded the remaining protesters, who opened umbrellas.

A group of protesters rushed back into the chamber and dragged out those who had wanted to stay. “We leave together!” they shouted.

Outside, police fired tear gas canisters at the protesters, acrid smoke billowing into the air.

Violence had broken out Monday morning as hundreds of police officers used tear gas and batons against thousands of protesters occupying the legislative complex in the lead-up to a flag-raising ceremony that Lam and other officials attended indoors under high security.

Tensions were high after hundreds of thousands of pro-police demonstrators clashed with extradition bill protesters Sunday afternoon, spitting and throwing mud at a group of protesters under the legislative building.

Three protesters have died in the last two weeks, leaving messages opposing the extradition bill before jumping off tall buildings, including two on Saturday and Sunday nights. Although civil society organizations spread mental health warnings to prevent copycat suicides, protesters have called the deceased “martyrs,” laying flowers and candles at shrines to their memory.

Crowds began gathering for the march at 1 p.m.

Thousands streamed past a mostly empty pro-Beijing festival, ignoring its booths and waiting for the march to begin. Groups of Christians prayed and sang hymns.

At the same time, pro-democracy legislators were arguing with a small group of young, angry protesters at the legislative building. The protesters wanted to charge into the building. The legislators tried to persuade them not to.

Leung Yiu-chung, a 66-year-old legislator, threw himself in front of a glass wall, holding out his arms. A masked protester tackled him to the floor. Within seconds, protesters managed to bash a heavy metal trolley into the glass wall.

The protests escalated from there, though many of the people marching just over a mile away disagreed with what was happening at the legislative building.

“Obviously we don’t support this kind of violent activity,” Agnes said. “It seems like it’s totally out of control.”

“We don’t want to risk exposure to danger. We want to have a peaceful protest, to make the government have a positive reaction.”

Her son Alex, 14, said he disagreed with protesters breaking the glass walls because it would give the government an excuse to label all demonstrators violent.

“The government can use this as an excuse,” he said. “You take a minority and treat them as the majority and say everyone is very violent.”

But the government should de-escalate the situation by responding more fully to people’s protests, said Alex’s father, Shing, 54.

“The government is in a monologue. They are really representing the central government [in Beijing], when they should speak from Hong Kong people’s side,” he said, adding that he didn’t support protester violence, but also distrusted the Chinese government.

Monday’s march was smaller than the last two — 550,000 participated, according to organizers — in part because many of the younger protesters, those in their 20s and younger, were busy besieging and charging the legislative complex.

Some older protesters who chose to march instead of charge said they understood why the younger protesters had become violent.

“They’re so angry. They don’t have votes or any actions that count. They don’t have another way to do this,” said Au Yung Man-ong, 68, waving a sign that said “Struggle Until the End.” He’d come out Monday because he felt in pain, he said, pointing to his chest.

“Three young people committed suicide,” he said. “I’m hoping Lam can step down and withdraw the bill. It’s a small act, easily solved. But she thinks saving her face is more important than people’s lives.”

Organizers changed the marching route to avoid the legislative complex because of the violence. But as the march reached Admiralty district, younger protesters ran out to the main road, waving their arms and calling for the approaching crowd to turn and join their occupation.

Some split while others marched on. The government “strongly condemned” the protesters who’d charged, calling them “extremely violent.”

As the afternoon progressed, more and more demonstrators from the march began streaming into the legislative building area, joining the young protesters — though many newcomers kept a safe distance by watching and supporting from pedestrian overpasses.

Ronnie Chow, 25, sat on the floor with his friend Edward Tsang, also 25. They’d covered their arms and legs with cling wrap as protection from pepper spray and tear gas.

“We’re here to free Hong Kong,” Chow said. He’d arrived at 6:30 a.m. without a plan, he said, except to make the government hear the protesters’ voices.

“A million people on the street, and the government ignores us. Two million people on the street, and the government ignores us. So we agreed on action to show the government we want to be free. We want our own future,” Chow said.

Tsang and Chow didn’t participate in smashing the glass walls, but didn’t oppose the violence either.

“We don’t say we support them, but we don’t blame them. Everyone is just doing what they can,” Tsang said. He’d participated in the Umbrella Movement five years ago, but thought it was a failure, as were the nonviolent methods protesters have used so far.

“We tried peaceful protesting. We sang songs. Today, we don’t sing songs. We don’t walk peacefully,” Tsang said. “The government just ignores us. No matter how many people, no matter what generation. Teenagers, old men, they don’t care.”

They didn’t have a strategy or an idea of what methods might work better than peaceful protest.

“Three people committed suicide. Hong Kong people are desperate. My generation is desperate,” Tsang said. “We don’t know what to do. We just try our best.”

As dusk fell, protesters dismantled a metal fence outside the legislative building, pulling its bars down like spears that they added to makeshift barricades.

They began ramming the building’s doors, breaking more and more glass panes, then bashing a metal screen inside as police yelled at them from behind it.

“Hong Kongers, add oil!” a growing mass of protesters chanted in rhythm with those ramming the doors in the front.

By 9 p.m., the protesters had stormed the building. A fire alarm blared nonstop as they surged inside, charging through the building with metal barricades and spraying anti-government graffiti on the walls.

Police were nowhere to be seen as the protesters entered the legislature’s main chamber, spraying “Withdraw the evil law,” “Anti-extradition” and “Carrie Lam step down” on the walls.

They hung a British version of the Hong Kong flag over the speaker’s chair.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.