In Hong Kong, a single mom faces a bitter backlash against mainland Chinese

- Share via

Reporting from Hong Kong — The only person Mai Han couldn’t hide her mood swings from was her 10-year-old daughter, Alice. The anxiety came in bursts; depression sucked at her like quicksand.

Outside, Han kept a calm face. She was an outsider in Hong Kong, where many locals already resented mainland Chinese. She had to blend in, speak Cantonese, pretend that they were a normal mother and child like everyone else.

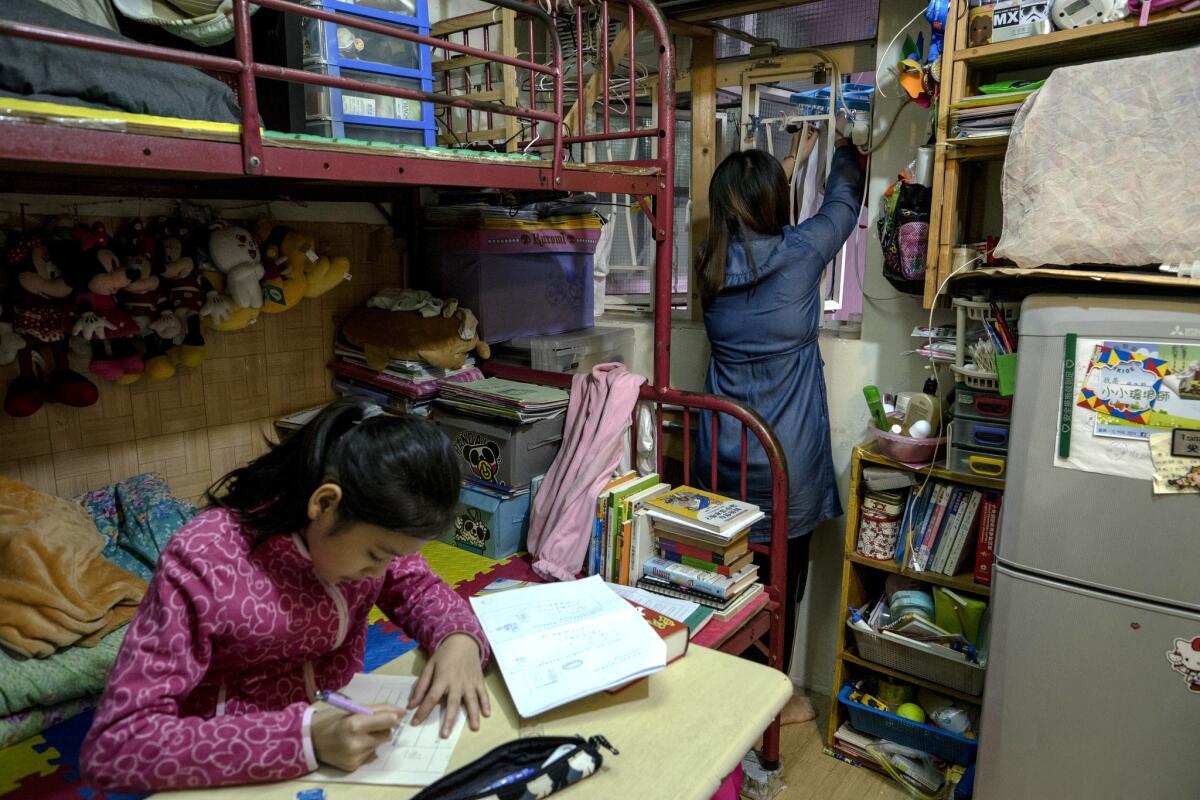

But at home, where Han cooked next to a toilet while Alice practiced piano on the top of a bunk bed in their rented 49-square-foot room, Han sometimes exploded.

They were living off Alice’s welfare, $520 a month, because Han couldn’t work. Divorced from her Hong Kong husband before she got a one-way permit, the document that allows people from mainland China to move to Hong Kong through family reunion, she was ineligible for working rights.

Many Hong Kong locals oppose the one-way permit system, claiming mainlanders are overcrowding housing and welfare systems; one lawmaker recently pushed to slash the number of permits in half.

Hong Kongers also worry that allowing in more people with allegiance to the Communist Party will enable slow erasure of the rule of law and freedoms of speech, press and assembly that set Hong Kong apart from mainland China.

Beneath the public’s anxieties about migrants lies a deeper fear that losing control of the border means losing control of Hong Kong’s future, as mainland China exerts greater control. For mothers like Han, that burden is hard to bear.

“We’re not just sitting and waiting to be fed,” Han said. “I can do any work. I’m not picky, as long as I can take care of her.”

Han, 45, has been hoping for a one-way permit since 2006, when she got married and left Hainan, China. But Han says her ex-husband — with whom she’s cut off contact — was unreliable and would disappear, leaving her alone with the baby to face debt collectors. “Strange men come to my house to ask for money…. You’re just afraid,” Han said.

After six years of marriage, the couple divorced. Han decided to stay in Hong Kong because there were better opportunities for Alice, who was born into residency.

About 30% of Hong Kong marriages are “cross-border” unions with a mainland spouse. Their children are residents upon birth, but the mainland spouses wait an average of four years to get a one-way permit. In the meantime, they cannot work legally and must travel back to mainland China every few months to renew visitor visas.

Han’s application was rejected after she divorced, and there’s no allowance for parents to get a permit through resident children. But some single mothers have managed to get permits.

Beijing decides who gets the permits, a fact that rankles many in Hong Kong, a special administrative region with some autonomy from China.

Lawmaker Gary Fan recently proposed Hong Kong assert authority over approvals, halve the number of permits and require applicants to show financial stability. Fan’s motion on March 22 failed, but it stoked a clash over whether mainlanders pose a threat to Hong Kong’s identity.

On the morning Fan made his motion, supporters stood in front of Hong Kong’s legislature holding pictures of the Titanic. “Too many people, the boat will sink,” their signs read.

Chan King-ming, a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, came to support the motion. He said Hong Kong should control the permits and recruit professionals.

“The number of, I wouldn’t call that low quality, but substandard people coming down — they cannot really make Hong Kong excel,” Chan said.

Most of Hong Kong’s population are Han Chinese who came from the mainland before 1997, when the region reverted from British to Chinese rule. Ethnically, the newcomers and locals are mostly the same. But they diverge when it comes to identity and relationship to Communist Party-governed China.

Claudia Mo’s family came to Hong Kong in the 1950s, fleeing communist rule at the end of the Chinese civil war. Now the newcomers come with the party’s approval, she said in an interview. “You can’t help thinking they are recolonizing Hong Kong.”

Mainland newcomers — Chinese migrants who have lived in Hong Kong for less than seven years — account for just over 2% of Hong Kong’s 7.4 million residents, down from previous years, according to Hong Kong census statistics from 2016. Last year, 42,331 one-way permits were issued, a decrease from the two previous years. But local hostility has increased.

Mo said she isn’t opposed to “real” family reunions, but believes Beijing turns a blind eye to marriage and immigration fraud for political reasons.

“They’re here to change Hong Kong,” Mo said of migrants, “to disappear Hong Kong.”

The day Fan proposed cutting permits, Han marched in front of the legislature building with other mainland women, some pushing babies in strollers. They waved signs reading, “Family is the foundation of society” and “Reunion is a human right.”

Sze Lai-shan, a social worker with the Society for Community Organization, wielded a megaphone: “These people are Hong Kong people’s family.”

Hong Kong has an aging population and a labor shortage, and mainland migrants are filling that gap, Sze said later in an interview.

The elderly accounted for 60% of Hong Kong’s welfare recipients from 2017 to 2018, according to government statistics. New migrants made up 4.8% of welfare recipients, even though their average poverty rate was higher than that of locals.

“If you’re lower class, wherever you go, no place welcomes you,” Sze said.

Sze, who moved at age 11 to Hong Kong from Fujian province in 1982 to join her grandmother, agreed that Hong Kong’s government should have authority over one-way permits — to expedite the family reunion process for the most vulnerable.

Hong Kong aims to solve its housing crisis with an $80-billion artificial island »

“We don’t have enough housing or medical workers, but these are not the fault of immigrants,” the social worker said. “This is the government’s problem.”

Lawmaker Fernando Cheung agrees. Hong Kong’s population growth has been below 1% for the last two decades, and poor planning has caused the shortages, he said. “The culprit is not immigrants.”

Name-calling feud escalates between Hong Kong and mainland China »

But since Hong Kong’s handover in 1997, an uncontrolled influx of Chinese tourists — a record high of 65.1 million in 2018 — has angered locals, who have called mainlanders “locusts.”

Many Hong Kong natives, raised with British sensibilities, resent what they see as uncouth mainland behavior: littering, spitting, urinating in public, smoking and dropping unseemly sums of money on gaudy luxury shopping sprees.

In retort, mainlanders have called Hong Kongers the “running dogs” of the British.

Hostility toward tourists has spilled into attitudes toward migrants, said Kai-chi Leung, a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong who studies mainland-Hong Kong relations.

“People don’t distinguish between different types of mainlanders,” Leung said.

“For a long time, Hong Kong welcomed immigrants from mainland China,” he said. But the power differential between Beijing and Hong Kong has changed that.

Leaders of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy Umbrella Movement have been imprisoned. Booksellers who sold controversial titles about mainland politicians have disappeared into Chinese detention. Locals now make comparisons with Tibet or Xinjiang, also supposedly autonomous regions that Beijing strictly controls.

“The fear of being unable to control the border is a manifestation of being unable to control the future of Hong Kong,” Leung said. “That fear is very real.”

Mai Han has seen discrimination against mainlanders. In response, she tries harder to integrate — to stand in line, to be polite, to be self-aware.

“I can only take care of my own behavior. If I can fix my own actions, fewer people will look down on me,” she said. “People will change their views of you if you keep doing the right thing.”

That’s what Han taught her daughter, so that no one would treat her as if she wasn’t from Hong Kong.

“She is a Hong Konger,” Han said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.