In Sinaloa, the drug trade has infiltrated ‘every corner of life’

- Share via

Reporting from Culiacan, Mexico — Yudit del Rincon, a 44-year-old lawmaker, went before the state legislature this year with a proposition: Let’s require lawmakers to take drug tests to prove they are clean.

Her colleagues greeted the idea with applause. Then she sprang a surprise on them: Two lab technicians waited in the audience to administer drug tests to every state lawmaker. We should set the example, she said.

They nearly trampled one another in the stampede to the door, Del Rincon recalled.

Del Rincon wasn’t all that shocked. She was born and bred here in the Pacific Coast state of Sinaloa, home of the drug racket’s top leaders, its most talented impresarios and some of its dirtiest government and police officials.

Swaths of Sinaloa periodically become no-go zones for outsiders; the central government abdicated control long ago. By one estimate, 32 towns are run by gangsters.

In Culiacan, the capital, casinos outnumber libraries, and dealerships for yachts and Hummers cater to the inexplicably wealthy.

This is where narco folklore started, with songs and icons that pay homage to gangsters, and where children want to grow up to be traffickers. How Sinaloa confronts its own divided soul offers insight on where the drug war may be going for Mexico, where more than 5,000 people have been killed in drug-related violence this year.

“The monster has lost all proportion,” said Del Rincon, who is a member of the conservative National Action Party.

A spunky woman with large eyes and hands that seem to be in constant motion, Del Rincon scans other tables at cafes where she meets people, making sure she knows who is within earshot; she lowers her voice when she names names. Her husband and closest confidant keeps tabs on her whereabouts throughout each day.

Such are the risks of speaking out.

“The narcos have networks meshed into the fabric of business, culture, politics -- every corner of life.”

Drug crops

Poppies and marijuana have been cultivated in the mountains of Sinaloa since the late 19th century. For decades, Mexican farmers harvested the crops, and entire dynasties of families dedicated themselves to the trade.

Except for one brutal crackdown in the 1970s, successive governments accommodated the drug trade, even as Mexico became a staging ground for Colombian cocaine headed to its biggest market, the United States.

Back then, one party ruled Mexico. The Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, controlled everything from the smallest of peasant groups to the presidency.

“The state was the referee, and it imposed the rules of the game on the traffickers,” Sinaloa-born historian Luis Astorga said. “The world of the politicians and the world of the traffickers contained and protected each other simultaneously.”

Slowly, the monopoly started to crack. Parties other than the PRI began to win elections, here and across the nation. Different faces joined regional legislatures, while the PRI struggled to hold on. Del Rincon’s PAN won the mayoralty of Culiacan and other posts across Sinaloa.

Finally, the PRI lost the presidency in 2000.

Political pluralism in Mexico may have made room for more firebrands like Del Rincon, but it also fed a free-for-all among trafficking gangs, which began to splinter and compete.

“The state was no longer the referee, and so the traffickers had to referee among themselves,” Astorga said. And that was not going to be a well-mannered process.

Gradually, law-abiding people learned a new code of conduct: Keep your head down, don’t ask too many questions, keep away from the restaurants and luxury boutiques where gangsters hang out. Family gatherings end early; everyone wants to get home soon after sunset.

“Mexico was a time bomb for a long time, and now it is finally out of control -- more guns, more money, more internal fights,” said Marco Antonio Castrejon, a dentist whose grandparents came down from the hills and settled in Culiacan about 60 years ago. Castrejon and his seven siblings worked hard, earned degrees and established legitimate professions, even as the men with guns and menacing swaggers took the streets.

About eight years ago, Castrejon kept his oldest boy from leaving Culiacan. Generations of the family had stuck together here. It was important to stay, he advised.

But this year, when his youngest turned 17 and wanted to leave, the door was open.

“I used to be afraid to have my children away from us,” said Castrejon, 48. “Now the greater fear is that they stay.”

Police at risk

Pedro Rodriguez, 41, has been a police officer for half his life in one of the deadliest places on the planet for cops. He got into law enforcement straight out of the army. He thought the discipline he admired in the military would continue in the Sinaloa police force. And he liked the authority that a policeman’s uniform gave him.

It all changed several years ago, he said.

“It used to be, as a uniformed police officer, I could raise my hand in the road and stop an 18-wheeler,” Rodriguez said. “Today the truck would run right over me.”

More than 100 police officers have been killed in Sinaloa this year, most of them gunned down. Countless others have fled, or taken bribes and changed sides. As much as 70% of the local police force has come under the sway of traffickers, by some estimates.

It is widely believed here that many legislators and other politicians are elected with the help of narcotics money. The exchange: veto power over the naming of top police commanders.

Rodriguez knows he can be betrayed by a corrupt fellow officer. So, he says a prayer every day before he leaves the modest home where he lives with his wife and four children. He works in a city that can seem normal on the surface, its streets clogged with traffic, office workers going to lunch.

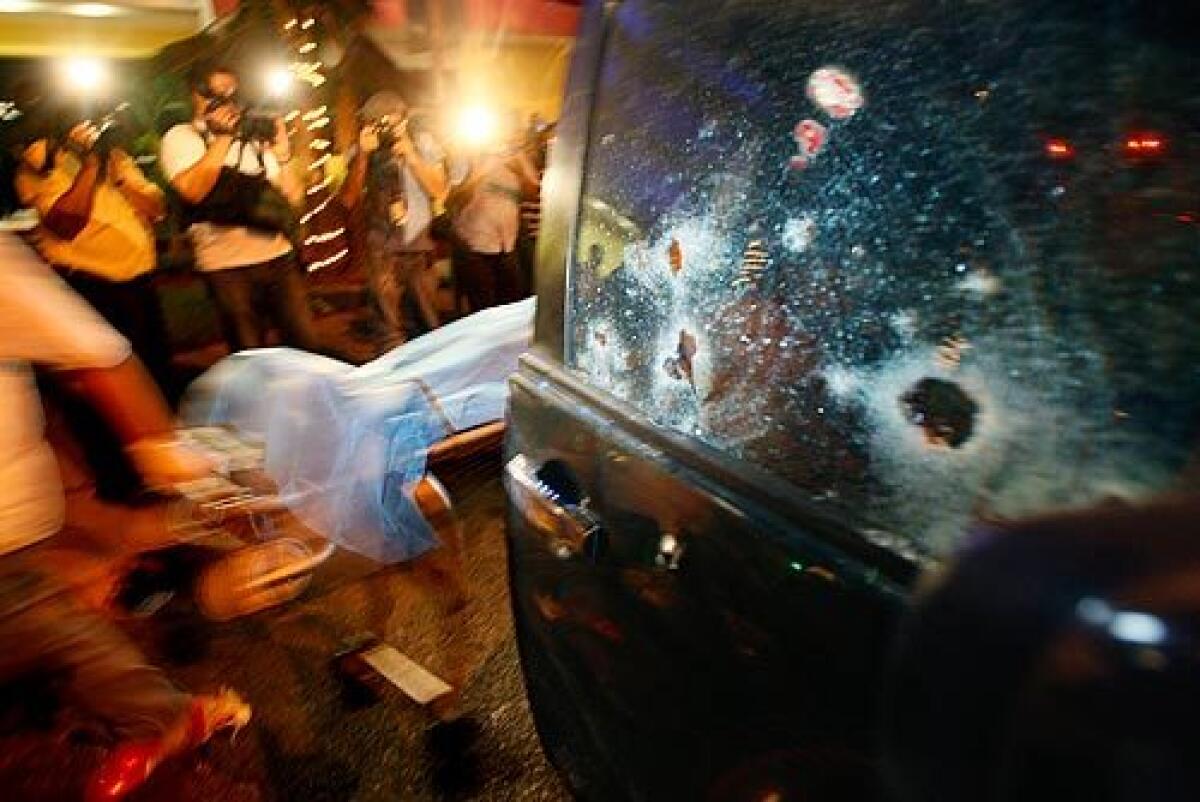

Then those same streets turn into a shooting gallery. Gunmen in dark-windowed SUVs open fire on rivals or cops, day or night. Five federal and state policemen were killed in a hail of bullets on Culiacan’s prominent Emiliano Zapata Boulevard one recent night. The truck with their bloodied corpses came to rest outside a busy casino under blue and purple neon lights and fake palm trees. It was the third time in recent weeks that an entire squad of agents was wiped out in an ambush. No one is ever arrested; shootings, even of cops, are hardly investigated.

“Twenty years ago we knew of the handful of big mafia dons, but they were discreet,” Rodriguez said. “Today we are dealing with the apprentices, who want to get rich very fast, who commit enormous excesses, who want to be noticed.”

That chaos might make some nostalgic for the old days, when a few Sinaloa dynasties dominated the drug trade, as they had for generations. Amado Carrillo Fuentes branched out from Sinaloa into Chihuahua in the 1980s and ‘90s and ran the Juarez drug network that made him one of the richest men on the planet, owner of a fleet of jets and vast real estate holdings the world over.

As the centralized system broke down, the Sinaloans met a new challenge: the Gulf cartel.

Based in the state of Tamaulipas, the Gulf gang was reputed to have ties with, and the protection of, Raul Salinas de Gortari, the brother of former Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari. After the arrest of its leader, Osiel Cardenas, the Gulf cartel became the first of the drug mafias to introduce a paramilitary army.

The narcotics ring recruited from Mexican and Guatemalan army special forces and formed the Zetas, ruthless hit men. The Zetas left one of their earliest calling cards in the town of Uruapan in Michoacan state in September 2006, when they tossed five severed heads onto the floor of a dance hall.

The Sinaloans in turn beefed up their security, and the Zetas on the other side trained additional recruits. Now several hundred, most between 17 and 35 years old, operate as mercenaries, investigators say.

“Each cartel needs its enforcement, its protection, its muscle, and that dynamic has been increasing exponentially in the last two years,” a senior U.S. law enforcement official said. “And now one side has to outdo the other.”

Crackdown

When Felipe Calderon took office two years ago, violence had already begun to surge. Calderon deployed the army days after his inauguration. The president, according to aides, was genuinely alarmed by the waves if killings sweeping the nation and the ability of traffickers to infiltrate politics and possibly even seek elected posts.

Even among Calderon’s supporters, however, there are complaints that the president underestimated the scope of the problem, dispatched an inadequately prepared army and is not fighting on the political and economic fronts. Consequently, the backlash has been bloodier than anticipated.

With plenty of money, the traffickers continue to protect themselves and buy their way into governments, says Edgardo Buscaglia, an expert on organized crime who advises Mexico’s Congress.

In the latest and potentially most explosive scandal, Sinaloan traffickers allegedly bought off senior antidrug officials in far-off Mexico City, acquiring inside information on Calderon’s ground war against smugglers.

Buscaglia warns against the “Afghanistan-ization” of Mexico, in which rival kingpins gradually take over different states.

“If one criminal organization takes over one state, and another criminal organization takes another, then you have the ingredients of civil war,” Buscaglia said. Mexico is not there yet, Buscaglia said, but that breakdown looms as a real danger.

Buscaglia believes traffickers already control 8% of Mexico’s municipalities, or about 200 cities and towns, based on his analysis of data such as arrest warrants issued for police, army detentions of elected officials, and the presence of sanctioned criminal activity such as drug sales and prostitution.

Leading the pack was the state of Sinaloa, with 32.

Jesus Vizcarra Calderon, the mayor of Culiacan, felt compelled late last year to deny rumors that his considerable fortune came from Sinaloan traffickers. Vizcarra has been tapped by the governor of Sinaloa to be the PRI’s candidate in next year’s gubernatorial elections.

Sinaloa state legislator Oscar Felix Ochoa also denied criminal activity after his three brothers were arrested in June, allegedly holding nearly 40 pounds of cocaine, weapons and cash. At the same time, the army discovered a safe house harboring gunmen implicated in the slaying of federal police, with more than $5 million stashed in a strongbox. The house had belonged to Felix Ochoa, the army said.

Del Rincon, the crusading legislator, used to lead the charge against Felix Ochoa. One day, someone sent a funeral wreath to her home with her name on it.

She is more careful these days about attacking individuals, but she is more determined than ever to challenge a doped-up status quo.

“All society is contaminated,” she said. “We are being held hostage. . . . If we remain silent, where will we end up?”

After a lifetime struggling to keep her family safe from traffickers, Del Rincon was dismayed when her son started dressing like the buchones -- the young wannabes who emulate traffickers.

“If we don’t dress like this, the girls won’t even look at us,” she recalled her son saying.

“It is fashionable to be a narco,” Del Rincon said, shaking her head. “It’s status.”

In the cemeteries of Sinaloa, many members of the new generation rest, having met premature death. Families spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to erect mausoleums that adulate the life that put their kin in their graves. The crypts are built with imported Italian marble, mosaics, crystal chandeliers, Corinthian columns and French doors.

In one, “Lupito” rests in peace with his AK-47; “Beta,” “Payan” and dozens more take their journey to the afterlife amid statues of the Virgin Mary, and accompanied by bottles of tequila, cans of Tecate beer and packs of Marlboros.

The average age of these men, all buried in the last few months, is less than 25 years.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.