Insurers learn to pinpoint risks -- and avoid them

- Share via

NEWARK, CALIF. — Hemant Shah is in the business of creating catastrophes.

The computers at Shah’s Silicon Valley company, Risk Management Solutions Inc., contain mathematical models of every U.S. disaster from the 1812 earthquake that toppled chimneys in St. Louis to the 9/11 assault that brought down the twin towers in New York, as well as 100,000 synthesized “extreme events.”

RMS runs its disasters through your community — and sometimes right through your home — to see how you’d fare in a hurricane, hailstorm, earthquake, epidemic or terrorist attack. The firm sells its knowledge to insurance companies to help them decide whom to cover and how much to charge.

Since Hurricane Katrina last year, those decisions have been running pretty much in one direction.

Based in part on RMS’ predictions, companies like Allstate Corp., the nation’s second-largest property insurer, have gotten out of some lines of coverage altogether. It and other companies have spent the year dropping or paring back policies from Oregon to New York.

Figures from state regulators show that more than 1 million homeowners nationwide have had to scramble to land new insurers or learn to live with weakened policies. Tens of millions are likely to face rate increases between 20% and more than 100%, according to regulators. And this may only be the beginning.

“Between hurricanes along the East and Gulf coasts and earthquakes along the West Coast, it is an open question whether the private insurance industry will continue to insure the coastline at all,” said University of Pennsylvania economist Howard Kunreuther, one of the country’s foremost authorities on disaster.

RMS is at the vanguard of a technological revolution that’s reshaping the nation’s $626-billion property casualty insurance industry. The industry, once synonymous with green eyeshades and airless statistics, is embracing a new generation of powerful computer techniques to learn everything it possibly can about you — or at least people very much like you — your health, habits, houses and cars. It is using this new trove of data to replace traditional uniform coverage at uniform rates with an increasingly wide array of policies at widely varying prices.

Industry executives say the aim is to create a finely tuned system in which companies can better manage the risks they bear while consumers can more carefully pick the protection they need and pay just the right amount for it.

As insurers become more adept at the techniques, “American consumers can be more assured that their companies will be there when they need them to pay their claims,” said Robert P. Hartwig, chief economist of the industry-funded Insurance Information Institute in New York.

The new techniques are already paying off for insurers. Despite Katrina and a string of other big storms last year, industry profits hit a record $40 billion-plus. With the luck of no major storms so far this year, profits are in line to reach as much as $60 billion.

But some regulators, economists and consumer advocates contend that the industry’s growing use of sophisticated computer-aided methods is producing side effects that could undermine the very nature of insurance.

Traditionally, insurance companies group people facing similar dangers into pools. Company actuaries determine how often events such as illnesses or accidents have befallen pool members in the past and how costly those occurrences have been. Insurers set their rates based on the frequency and loss histories assembled by their actuaries.

A key characteristic of this approach is that there’s an incentive for insurers to assemble pools as big as possible. The bigger the pools, the more the actuaries have to work with. And the more they have to work with, the more accurate their frequency and loss numbers.

But the question has always hung in the air: What if insurers could know more in advance? What if they could outflank their history- and numbers-bound actuaries and predict who’s more likely to be hit with setbacks in the future? What if they could charge such customers steeply higher rates, or avoid them altogether? Wouldn’t that boost profits, making shareholders and executives happy, and ensure that insurers had plenty of cash on hand to pay the smaller claims of the safer customers?

That is the promise of catastrophe models like RMS’. And it’s the promise of new “data-mining” methods that let companies use a person’s income, education or ZIP code to predict future claims. That in turn encourages insurers to raise rates or refuse coverage for the very people who need it most — low- and moderate-income families, for example, or those who’ve suffered such setbacks as unemployment.

As the industry expands its ability to “slice and dice” customers and applicants, Texas Insurance Commissioner Mike Geeslin, among others, worries that “the risk-transfer mechanism at the heart of insurance could break down.”

If that happens, Geeslin warned, “insurance will stop functioning as insurance.”

*

Rushing into harm’s way?

By providing companies with so much information about individual properties and policyholders, new techniques such as RMS’ are riveting insurers’ attention on how choices made by individuals are raising the cost of disasters, while dampening industry interest in the kind of broad risk-reduction measures that were once a hallmark of American insurance.The industry now contends that one of the chief reasons Katrina and other recent disasters caused so much damage — and produced such huge insurance claims — is that Americans are rushing into harm’s way by moving to hurricane-prone coasts and earthquake zones like California.

And one of the chief reasons, according to this argument, is that they’re being subsidized by homeowners insurance premiums that have been held artificially low by state regulators.

The argument has attracted a wide following in the last year both inside the industry and out.

Ten of the nation’s top climate experts, including retiring National Hurricane Center Director Max Mayfield, issued a statement this summer warning that “the main hurricane problem facing the United States is our lemming-like march to the sea,” and laid much of the blame on “government policies that serve to subsidize risk.”

Allstate Chief Executive Edward M. Liddy made a similar point in a San Francisco speech a few months earlier, saying, “The risks keep rising because people continue to flock to places that are exposed to catastrophe. Population in earthquake-prone and coastal areas is growing faster than the rest of the country, and the increase is by a wide margin.”

The solution, according to industry leaders and many policymakers, is to let insurers charge higher rates in danger zones to discourage people from moving there, and to make those who live there pay for the additional risks they run.

The problem is that some key statistics don’t seem to support the argument.

Though government statistics do show various sorts of growth in the nation’s danger zones, they don’t show it occurring at an appreciably faster pace than for the country as a whole.

Census figures, for example, show that the population of coastal and earthquake counties grew at an annual average rate of 1.56% between 1980 and last year. But they show that the U.S. population overall grew at a reasonably close pace of 1.24%. Other growth measures show a similar pattern.

Proponents counter that these averages mask spectacular growth in such vulnerable places as Miami-Dade County, Fla., and Dare County, N.C. But most of Miami-Dade’s growth was in the 1980s and the early and mid-1990s, and since then its growth rate has settled back to the national average. And in the case of Dare County, the growth, while tremendous in percentage terms, has only involved an increase from 13,400 people in 1980 to just 33,900 last year.

What this suggests is that rising disaster damage and costs are more a function of demographics than insurance rates.

“You simply cannot make the case from the numbers that America’s coastal counties have grown at a disproportionately faster rate than the country as a whole over the last 25 years,” said Judith T. Kildow, who runs the largely government-funded National Ocean Economics Program at Cal State Monterey. If anything, Kildow said, “the numbers show that growth is now greater inland.”

Meanwhile, insurers’ intense focus on individuals appears to be reducing companies’ historic interest in society-wide risk reduction measures.

When electricity was introduced to cities in the 19th century, the industry founded Underwriters Laboratories Inc. to set safety standards for wiring and appliances. When highway deaths climbed in the mid-20th century, the industry created the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety to perform crash tests that helped pressure automakers into building safer cars.

This time around, industry spokespeople cite premium discounts for homeowners who take protective measures such as installing storm shutters. They note company efforts to press for stronger local building codes. And they point to the industry’s establishment of the Institute for Business & Home Safety in Tampa, Fla., which, somewhat like Underwriters Laboratories, sets standards for disaster-proofing homes and runs a certification program.

But most companies acknowledge that their discounts are too small to attract many takers. Except in Florida and California, industry lobbying for stronger building codes has produced decidedly mixed results. And as for IBHS, it appears to be dwarfed by the magnitude of the problem it has been assigned to tackle.

Harvey Ryland, a former deputy director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency who now heads IBHS, recently said that 100 institute-certified houses were available for purchase, with an additional 2,000 or so planned. This is at a time when census figures show that the number of housing units in the nation’s coastal and earthquake counties is nearing 40 million.

*

Missing the big picture

Hemant Shah did not set out to cause a revolution in insurance when he started Risk Management Solutions. He and a friend were simply trying to ace a business-school course at Stanford University in the late 1980s when they came up with the idea for the firm.Although the company employs more than 1,000 people and reportedly has annual revenues of $200 million, there remains a college-bull-session quality to much of its operation. There’s also an ivory-tower insularity to some of the consequences of its work.

When RMS specialists recently gathered in a sleek company conference room to discuss their analysis of millions of insurance claims from the last two years, they were particularly excited about the finding that big houses seemed to fare better in hurricanes than small ones. The group buzzed with ideas about why this might be. But until a visitor raised the issue, no one mentioned the socially dicey implication that owners of big homes could end up being charged lower insurance premiums than those of small ones.

A similar insularity was on display in the spring when — faced with two years of intense hurricanes that had resulted in higher-than-anticipated damage claims — RMS dropped its reliance on historical averages to predict storms in favor of the views of a four-expert panel. The panel concluded that the chance of big hurricanes occurring off the U.S. coast was substantially greater than previously thought, and thus so were the likely losses of RMS’ insurance company clients.

RMS’ move set off an immediate uproar. Insurers redoubled efforts to win big premium increases. Consumer advocates accused the company of tailoring its results to help justify rate hikes. Some scientists complained that the firm’s change of method violated a basic principle that, absent evidence to the contrary, the past is the best predictor of the future.

Through it all, RMS remained unfazed. Shah said the firm must remain above the fray to do its job. “Our view of the world is that we try to understand the risk,” he said. “We try not to be involved in the consequences of our findings.”

Of course, the latest round of rate hikes and coverage cutbacks is not RMS’ handiwork alone, nor the first by residential insurers. Indeed, many of the recent changes are extensions of ones begun after the nation’s last major run-in with natural disasters, including the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake in the Bay Area, the 1991 Oakland firestorm, 1992’s Hurricane Andrew in Florida and the Northridge earthquake in 1994.

Those disasters destroyed tens of thousands of homes and uprooted hundreds of thousands of people. They also scrambled the finances of many insurance companies, including 11 in Florida that went bankrupt. The industry responded by seeking state help and changing the terms of homeowners policies.

After lengthy political battles with state regulators, insurers were effectively relieved of responsibility for covering the wind and quake dangers that had just cost them so dearly. Those jobs were shifted to a set of state-created companies and agencies.

In California, the insurers were no longer required to sell earthquake insurance as part of their homeowners policies. Henceforth, most homeowners would get that coverage from the California Earthquake Authority. Although the public agency could tap the insurance companies for money in case of trouble, CEA’s creation effectively capped the amount that the industry could lose to quakes at a comparatively modest few billion dollars.

In Florida, the state set up a fund to provide insurers with low-cost insurance of their own to help cover wind damage claims. In addition, Florida officials established what eventually became Citizens Property Insurance Corp. as a home insurer of last resort. It recently decided to create a similar organization for commercial property.

The original idea behind Citizens was that the private industry would eventually take back the policies dropped after the 1992 hurricane, and Citizens would quietly go out of business. But the opposite has happened. The company is now Florida’s largest homeowners insurer with more than 1.2 million policies, virtually all of them on homes along the coast.

“It’s not a sustainable situation,” said Bruce Douglas, a Jacksonville financial executive who chairs Citizens’ board of directors. “Our entire portfolio is high-risk; we have no diversification.”

The industry’s other response was to begin changing the language in homeowners policies.

Industry executives maintain that the changes have been solely intended to clarify what companies cover. “Insurers think of what they’re doing as bringing policies back to what they thought they were selling in the first place,” said Rade T. Musulin, a prominent official with the American Academy of Actuaries, an industry professional organization, and a former vice president with Florida Farm Bureau Insurance Cos.

But regulators say many of the changes have shrunk the protection that policyholders get.

“Insurers are taking on a helluva lot less risk than they used to,” complained California Insurance Commissioner John Garamendi.

The story of a single change illustrates the gulf that has opened between what insurers say they are selling and what most homeowners think they are buying.

When the late-1980s-to-early-’90s disasters hit, the gold standard for homeowners was the “guaranteed replacement cost” policy. Industry executives assert that such policies have not been as common nor as generous as is often thought. They say that virtually all included dollar limits.

But regulators interpreted “guaranteed replacement cost” to mean that insurers had to replace a destroyed home essentially no matter what the limit or expense to the firms. And most policyholders — both before and since the ‘80s and ‘90s disasters — have assumed that this is the kind of coverage they purchased.

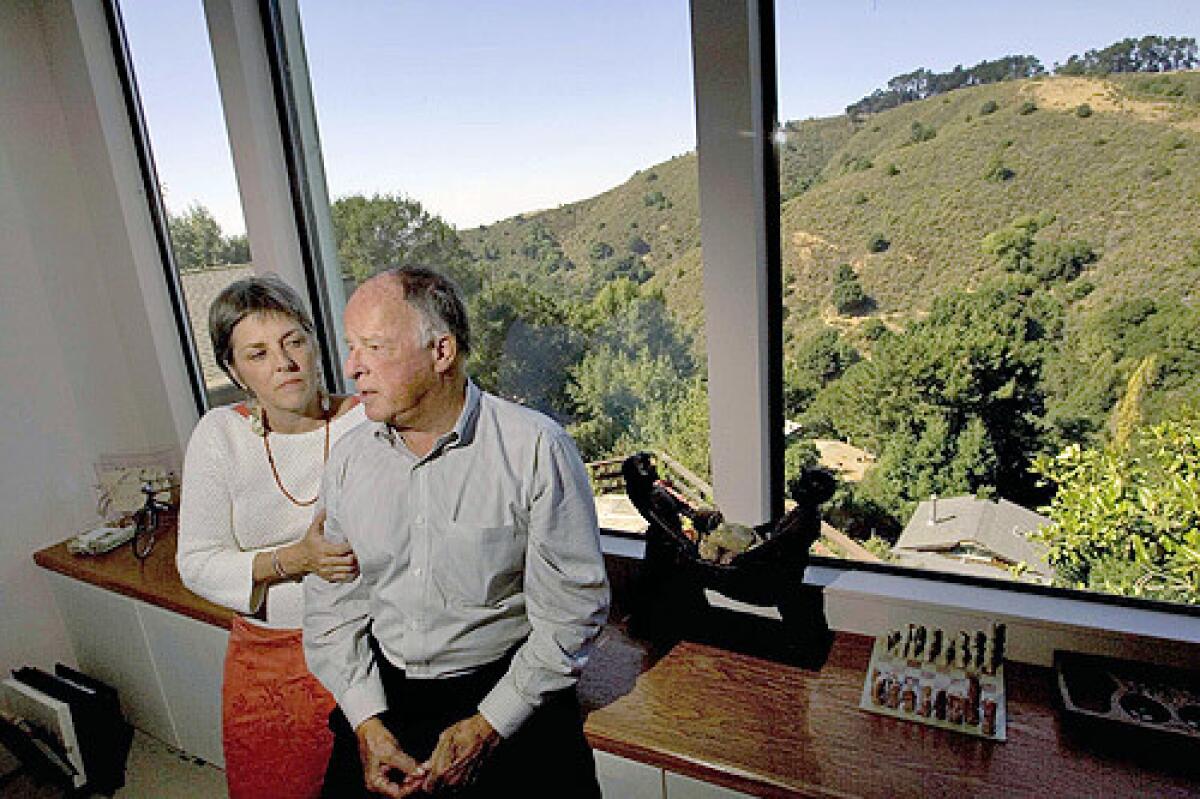

In the case of Peter Scott and his wife, Teresa Ferguson, that assumption was reinforced by a series of phone conversations with their insurance agent in the months before the Oakland firestorm. Scott, an architect, and Ferguson, an accountant, lived with their children and his sickly mother near the Oakland-Berkeley border. When a colleague of Ferguson’s complained that she’d had trouble collecting on an unrelated homeowners claim, Ferguson made her husband dig out their policy with USF&G (now largely defunct) and review details with their agent.

“Did he say we were covered?” she remembers asking her husband after his call to the agent.

“I guess I didn’t ask it quite that way,” he replied.

“Well, call him back,” she said.

The couple said they were told that they were fully covered. Just to make sure, they put together a 13-page list with everything from the kitchen plates to the grand piano and sent it to the agent.

The fire on Oct. 20, 1991, killed Scott’s mother, Frances Gray Scott, and leveled the family house. Only after the disaster did they learn that theirs was not a guaranteed replacement cost policy, but could have been for only a few more dollars a month.

Records show that Scott and Ferguson, who had almost paid off their old mortgage, borrowed and spent almost $550,000 rebuilding and refurbishing. Although the insurer eventually paid about $400,000, that still left the couple more than $100,000 short. The shortfall, their new loans and children’s education costs have kept the couple working, although Scott, at 72, wants to retire. “Maybe in three to five years,” he mused.

Efforts to reach USF&G were unsuccessful. The Baltimore-based company stopped selling full-line insurance in the mid-1990s and was subsequently acquired.

After the 1991 disaster, companies began dropping guaranteed replacement cost policies in favor of similar-sounding but substantially more limited “extended replacement cost” ones. Under the latter policy, an insurer is obligated to pay only up to the dollar amount that a policyholder specifically buys plus, typically, an additional 20%. By now, industry executives say, the former type of policy has all but disappeared.

The problem is that few policyholders understood what was at stake in the word change. Encouraged in part by industry advertising, they continued to believe that their insurance would replace their houses if they were destroyed. The misunderstanding became apparent when wildfires swept Southern California in the fall of 2003. Terry and Julie Tunnell were among those who lost their home in the Scripps Ranch area of San Diego.

The couple said they purchased a guaranteed replacement cost policy from State Farm when they bought the single-story, 1,738-square-foot house, their first, in 1992.

Terry, 46, is the chief financial officer with a San Diego company and Julie, 41, is an accounting professor at San Diego City College, so they are trained to keep tabs on such matters as insurance. But at some point — without their knowledge, according to the Tunnells — their coverage was switched to an extended replacement cost policy, with the same premiums as their previous policy. As a result, when the fire struck, they found themselves $300,000 short of what was needed to rebuild and replace their belongings. A State Farm spokesman said the company converted all its guaranteed replacement cost policies in 1997, and notified all its customers.

Once, the Tunnells’ biggest financial aims had been to pay off their mortgage in 15 years and save for their young son Brian’s college education. But now, to try to make back their loss, they’ve placed a huge bet on California real estate. They’ve taken out a new mortgage that’s more than double their previous one and built a house twice the size of what they lost in hopes that its value will appreciate faster than their expenses.

“Before the fire, we figured we were pretty much set,” Julie said. “We were well on our way to paying off our mortgage. We had some savings and thought retirement was well in sight. We thought we had good insurance with America’s most trusted insurance company,” she said.

“Boy, were we ever wrong. Our lives were completely changed.”

The Tunnells and other policyholders had better prepare themselves; more changes are on the way.

*

Breaking tradition

Give RMS a street address almost anywhere in the country, and it can pull up what’s at the location, and tell you when it was built and out of what. Then it can run hundreds, sometimes thousands, of simulated disasters across the structure. Those that bear up well are good bets for insurers; those that don’t are bad ones.At the same time, so-called data-mining companies use years of insurance company data to generate a computerized library of correlations between claims and such personal attributes as income, education, ZIP code and credit score. That library can then be used to predict whether that person will file a claim in the future. Those who the program predicts won’t file are good bets for insurers; those who it predicts will file are bad.

RMS’ techniques and those of the data-miners share three crucial similarities: They’re only possible because of recent advances in computing power. They generate predictions about individual people and properties. And they have set off a mad scramble among insurers to slice their once-broad pools of policyholders into finer risk categories.

Northbrook, Ill.-based Allstate now sorts its home and auto policyholders into 384 categories, up from the three that it used until a few years ago. At Bloomington, Ill.-based State Farm, the nation’s largest auto and home insurer, the number of categories the company uses has increased 100-fold. At Cleveland-area-based auto insurer Progressive, the number runs into the millions.

Insurance executives say that the rush to refine is producing positive results. It gives companies more detailed information about the risks they bear; allows them to offer lower rates to, for example, homeowners who live in safe places; and lets firms individualize policies to fit each policyholder’s needs. “It gets us closer to our customers,” said an Allstate spokesman.

But the ever-finer slicing appears to be having other effects as well, ones that worry a variety of regulators and insurance theorists.

States like California and Maryland have banned insurers from using credit scores, ZIP codes and other factors in deciding whether to cover someone, arguing that they unfairly discriminate against the poor and minorities. Washington state officials complain that the proliferation of categories and risk factors has so confused policyholders that the state now requires a company to provide customers written explanations whenever it gives them anything but its best rate.

“If I have a lot of house fires, [insurance companies] should charge me more,” said Washington state Insurance Commissioner Mike Kreidler. “But when insurers reach and grab information like credit or occupation or education, people say, ‘Wait a minute. I thought we were talking about insuring my home or auto. What does occupation or education have to do with it?’ ”

Some veteran observers wonder whether the intense focus on individual policyholders and properties is a recipe for business disaster.

“Insurers who look at each risk individually at the expense of broadly diversified pools are going to end up in the soup,” predicted author Peter L. Bernstein, whose book “Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk” traces the mathematical origins of the insurance industry. “Diversification, not flyspecking one risk at a time, is insurers’ optimal form of risk management.”

Perhaps most broadly, the new techniques appear to be dismantling much of what insurance traditionally has been about.

Until now, insurance of almost every type has performed two key functions.

The first is pooling. Anyone buying an insurance policy is, in effect, kicking into a pot that covers the cost of future bad events befalling a few of their number. The second is providing cross-subsidies. Some buyers are more likely to get nailed by bad events because, for example, their genetic makeup leaves them prone to disease or their houses are not built to the latest code, and others are less likely.

But for the most part, insurers have not known which policyholders fall into which category, so they have charged generally uniform rates, which means that those in the “more likely” category get a subsidy by being able to pay the same as those in the “less likely” one even though they might end up costing more.

However, as disaster models such as RMS’ and data-mining provide companies with increasingly detailed knowledge about individual policyholders, there are fewer and fewer pockets of such ignorance and therefore less and less room for cross-subsidies.

“Insurers are squeezing subsidies out of the system across the board, and they’re going to carry it absolutely as far as they can,” said Columbia University economist Bruce Greenwald.

On its face, the trend might seem a positive one. Among other things, it means that policyholders with good genes and safe houses can enjoy lower rates. But at least in some cases, Greenwald and others argue, the end of cross-subsidies spells trouble.

In the case of healthcare insurance, it would mean that a substantial fraction of the nation could no longer afford coverage. In the case of homeowners insurance, it ultimately might mean that large swaths of the nation’s coasts become unaffordable for all but the wealthiest Americans who can bear unsubsidized rates.

And this may not be where the dismantling ends. Some analysts say that the same kind of modeling and data-mining that’s helping companies squeeze out cross-subsidies could end up squeezing out much of the pooling in insurance as well.

As insurers use the new techniques to get ever-more-refined estimates of what individual policyholders are likely to cost in the future, they may be tempted to charge people closer and closer to full freight for treating an illness or rebuilding a fire-damaged home. Then even those who benefited from the end of cross-subsidies could see their rates go up as they effectively are asked to pay their own way, rather than share the cost by pooling with others.

Industry executives argue that competition among insurers will prevent such an eventuality. “I don’t think you’re ever going to get to the extreme of no pooling,” said Greg Heidrich, senior vice president of policy with the Property Casualty Insurers Assn. of America, one of the industry’s largest trade groups. But regulators are not as confident.

“When you begin to tailor or refine policies,” said Alessandro A. Iuppa, president of the National Assn. of Insurance Commissioners, which represents the nation’s 50 state insurance departments, “you could end up with people basically covering their own losses.”

But that, of course, would not be insurance.

*

When the risks are wrong

Hemant Shah will readily acknowledge that RMS’ model proved to be less than perfect during Hurricane Katrina. “We got a lot of things right,” he said, “but there are a few things we got wrong.”Among the wrong things: The model didn’t try to estimate the cost of flooding because that’s borne by the federal government. It missed the cost of pollution and of such things as power plant failures in distant locations. It underestimated the “business interruption” that came with the shutdown of the nation’s Gulf Coast.

Listening to the young executive’s list, it begins to sound as if the model captured most of what happened to the buildings, but missed much of what happened in between them.

But Shah and his colleagues are optimistic that problems can be fixed, the model improved. They are on the hunt for new terrain into which to expand their reach. Among the possibilities: modeling fire, one of the first dangers that the insurance industry offered to protect American homeowners against.

RMS Executive Vice President Paul VanDerMarck put it this way: “We think there are a lot of legacy assumptions built into how fire is managed and insured that may be incorrect or incomplete.”

*

peter.gosselin@latimes.com

*(INFOBOX BELOW)

Retreating from risk

Insurance company cutbacks have left more than 1 million coastal residents scrambling to land new insurers or learning to live with weakened policies. As insurers retreat, states and homeowners are left to bear the biggest risks.

Massachusetts

During the last two years, six insurers have stopped selling or renewing policies along the coast, especially on Cape Cod, leaving 45,000 homeowners to look for coverage elsewhere. Most have turned to the state-created insurer of last resort. The Massachusetts FAIR Plan, now the state’s largest homeowners insurer, recently received permission to raise rates 12.4%.Connecticut

Atty. Gen. Richard Blumenthal has subpoenaed nine insurance companies to explain why they are requiring thousands of policyholders whose houses are near any water — coast, river or lake — to install storm shutters within 45 days or have their coverage cut or canceled.New York

Allstate has refused to renew 30,000 policies in New York City and Long Island, and suggested it may make further cuts. Other insurers, including Nationwide and MetLife, have raised to as much as 5% of a home’s value the amount policyholders must pay before insurance kicks in, or say they will write no new policies in coastal areas.South Carolina

Agents say most insurers have stopped selling hurricane coverage along the coast. Those that still do have raised their rates by as much as 100%. The state-created fallback insurer is expected to more than double its business from 21,000 policies last year to more than 50,000.Florida

Allstate has offloaded 120,000 homeowners to a start-up insurer and has said it will drop more as policies come up for renewal. State-created Citizens Property, now the state’s largest homeowners insurer with 1.2 million policies, was forced to use tax dollars and issue bonds to plug a $1.6-billion financial hole due to hurricane claims. The second-largest, Poe Financial Group, went bankrupt this summer, leaving 300,000 to find coverage elsewhere. The state also has separate funds to sell insurers below-market reinsurance and cover businesses. Controversy over insurance was a major issue in this fall’s election campaign, causing fissures in the dominant GOP.Louisiana

The state’s largest residential insurer, State Farm, will no longer offer wind and hail coverage as part of homeowners policies in southern Louisiana. In areas where it still covers these dangers, it will require homeowners to pay up to 5% of losses themselves before insurance kicks in. In a move state regulators call illegal and are fighting, Allstate is seeking to transfer wind and hail coverage for 30,000 of its existing customers to the state-created Citizens Insurance.Texas

Allstate and five smaller insurers have canceled hurricane coverage for about 100,000 homeowners and have said they will write no new policies in coastal areas. Texas’ largest insurer, State Farm, is seeking to raise its rates by more than 50% along the coast and 20% statewide.California

The state has bucked the trend toward higher homeowners insurance rates with three major insurers, State Farm, Hartford and USAA, seeking rate reductions of 11% to 22%. Regulators have begun to question whether insurers are making excessive profits after finding that major companies spent only 41 cents of every premium dollar paying claims and related expenses. Alone among major firms, Allstate is seeking a 12.2% rate hike.Washington

Allstate has dropped earthquake coverage for about 40,000 customers and will have its agents offer the quake insurance of another company when selling homeowners policies in the state. Nationally, the company has canceled quake coverage for more than 400,000.Sources: Risk Management Solutions (map); interviews with state insurance regulators

**About this series

The insurance revolution is the latest chapter in a little-noticed change that’s transforming the material lives of many, perhaps most Americans — a quarter-century-long shift of economic risk from the broad shoulders of business and government to the backs of working Americans. Previous Los Angeles Times stories on this phenomenon, plus a profile of Risk Management Solutions founder Hemant Shah, can be found at http://161.35.110.226/newdeal .

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.