Obama honors Mandela during South Africa visit

- Share via

CAPE TOWN, South Africa — Nelson Mandela will leave a legacy that demonstrates the success of “acting on our ideas,” President Obama said Sunday as he tried to define his own imprint on a rapidly changing continent at a crossroads.

“You showed us how a prisoner can become president. You showed how adversaries can reconcile,” Obama said in a speech at the University of Cape Town, the signature event of his weeklong trip to Africa. “If there’s any country in the world that shows the power of human beings to effect change, this is the one.”

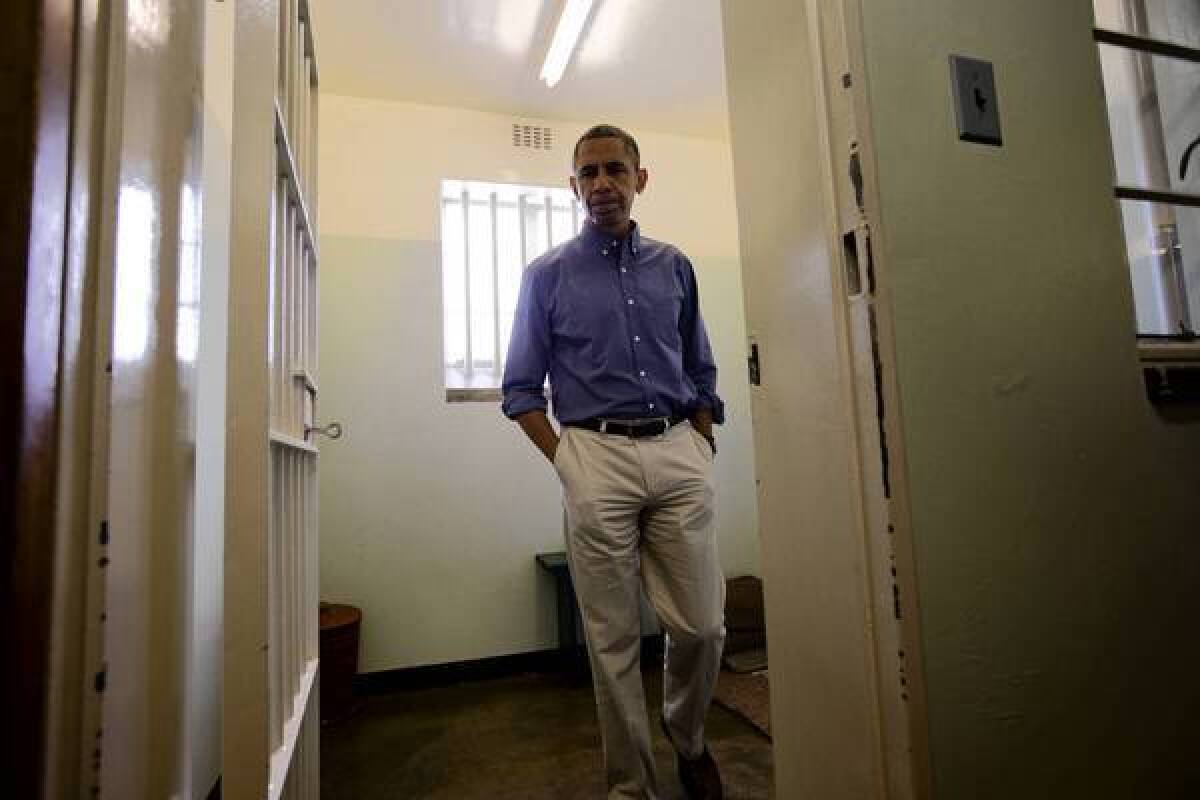

Obama’s words were the coda to a day spent honoring the man he calls a personal hero and credits with inspiring his first steps into politics. Earlier Sunday, the president and his family walked the stark lime quarry where the civil rights icon once hunched in backbreaking work, and the spare cell where Mandela spent 18 years confined for fighting a government ruled by a white minority.

Obama’s tour of the prison at Robben Island served as the symbolic union between the first African American president of the United States and the first black president of South Africa when there could be no face-to-face meeting. Mandela, 94, remained hospitalized in critical condition in Pretoria on Sunday, with his wife, Graca Machel, at his bedside and much of the world preparing for his death.

Mandela’s illness nearly overshadowed Obama’s primary task in his first major tour of the continent as president — answering those who say he has neglected a region poised for growth and rapidly shifting away from U.S. influence.

Obama announced Sunday that his administration would aim to double the number of people with access to power in sub-Saharan Africa, where nearly two-thirds of the population lives without electricity. He committed $7 billion over five years to the “Power Africa” initiative, federal money that will add to private investment and commitments from six African countries, he said. The first phase will aim to expand access to power for more than 20 million households, the White House said.

“I’m calling for America to up our game when it comes to Africa,” Obama said, adding that he would also be sending more trade missions, inviting African leaders to a summit in the U.S. next year and encouraging more exchanges with young people.

As U.S. influence has waned, other countries — most notably China — have rushed in with new investments. Obama argued Sunday that he welcomes such competition for Africa’s resources — “we want everybody paying attention to what’s going on here,” he said. But Obama is also under pressure to make the case that the U.S. is a ready, more reliable partner for African governments and workers.

On Sunday he outlined a case that relied heavily on the familiar promise to bring democratic institutions along with U.S. business. Obama said he would invest “not in strong men but in strong institutions” and respect women’s rights. Obama nostalgically evoked U.S. ideals, repeatedly referring to Sen. Robert F. Kennedy’s early call for racial equality, delivered at the same university in 1966.

But Obama also has been forced to address present concerns, including criticism over his counter-terrorism policies that have sparked some protests around his visit. Obama heard a pointed word on his security policies and his failure to close the Guantanamo Bay detention center from Archbishop Desmond Tutu on Sunday as he visited the anti-apartheid leader’s health clinic. Africans consider him one of their own, Tutu told the president.

“Your success is our success. Your failure, whether you like it or not, is our failure,” Tutu said. “We want you to be known as having brought peace to the world.”

But as he toured Robben Island with his family, Obama was looking back at the legacy of others. As he stood in the quarry, he was heard telling his daughters, Sasha and Malia, about Mahatma Gandhi’s early work in South Africa as a lawyer. “When he went back to India, the principles ultimately led to Indian independence, and what Gandhi did inspired Martin Luther King,” he said.

Obama first went to the site in 2006 as a young U.S. senator touring the continent where his father was born. He returned just seven years later as a gray-haired president with an entourage of security, prying media and his family — First Lady Michelle Obama, his daughters, mother-in-law Marian Robinson and niece Leslie Robinson.

The group was led through the tour by former prisoner Ahmed Kathrada, among the 33 leaders imprisoned with Mandela. Kathrada, Mandela and other apartheid fighters spent hours pounding on the rocks under the surveillance of a watchtower, eating lunch and using a bucket for a toilet in the same cave.

In all, Mandela spent 27 years in prison after being convicted of trying to overthrow the South African government. He was moved from Robben Island in 1982 and spent the remainder of his imprisonment on the mainland until February 1990, when he walked out of prison a graying, thin, wrinkled version of the man who went in. Four years later, he was elected president.

Obama and the first lady had been expected to visit Mandela during this long-awaited tour of Africa. Such a meeting would have been the first between the two since Obama was elected. But the visit was replaced by a phone call to Mandela’s wife on Saturday and a meeting with other family members, where he offered his support to the anguished relatives.

On Sunday, Obama offered his gratitude:

“On behalf of our family we’re deeply humbled to stand where men of such courage faced down injustice and refused to yield,” Obama wrote in the Robben Island guest book. “The world is grateful for the heroes of Robben Island, who remind us that no shackles or cells can match the strength of the human spirit. Barack Obama and Michelle Obama 30 June 2013.”

kathleen.hennessey@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.