Mistrust bedevils war on Mexican drug cartels

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — The U.S. has begun pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into Mexico to help stanch the expansion of drug-fueled violence and corruption that has claimed more than 5,000 lives south of the border this year.

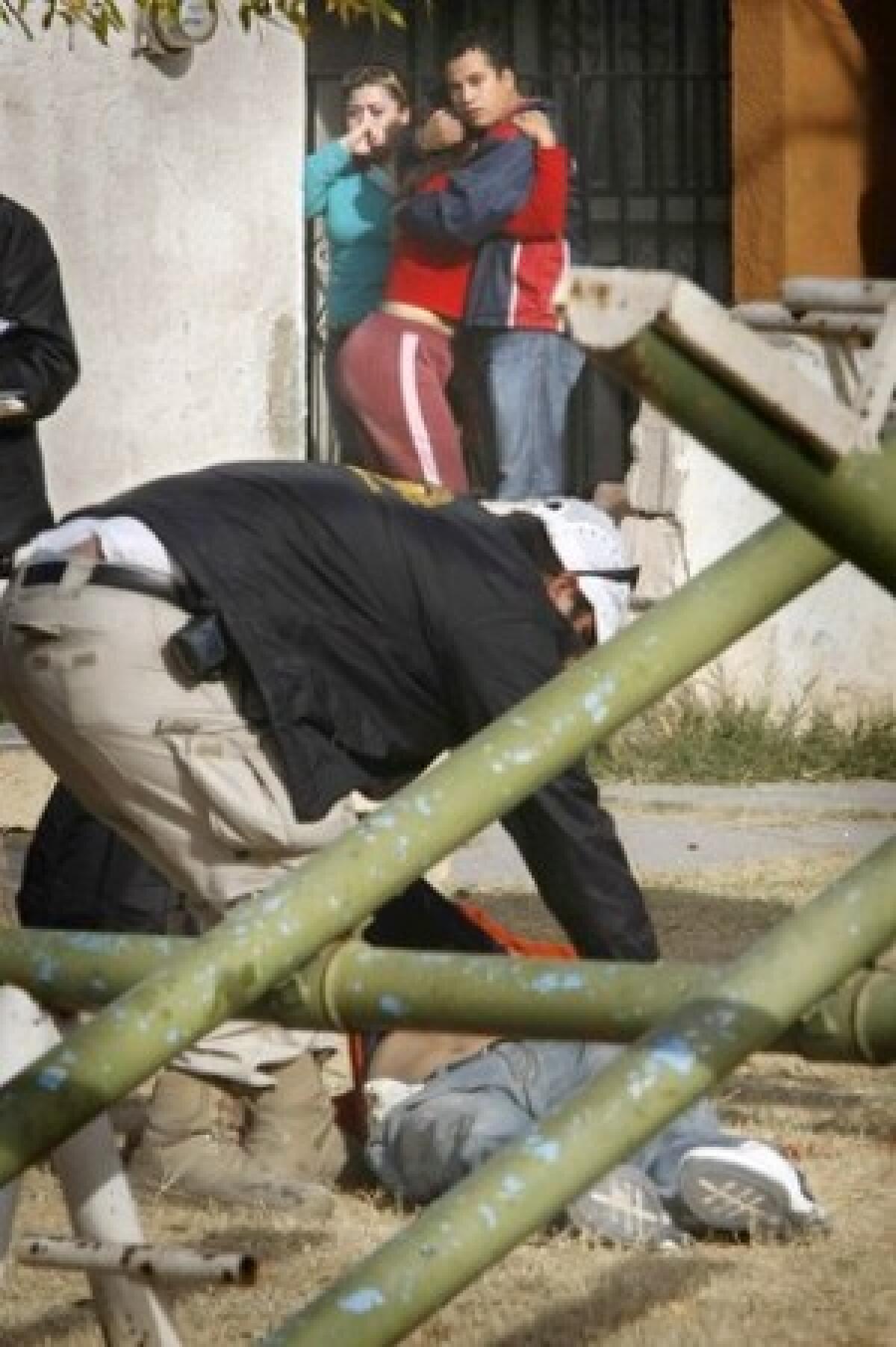

The bloodshed has spread to American cities, even to the heartland, and U.S. officials are realizing that their fight against powerful drug cartels responsible for the carnage has come down to this: Either walk away or support Mexican President Felipe Calderon’s strategy, even with the risk that counter-narcotics intelligence, equipment and training could end up in the hands of cartel bosses.

Both nations agree that the cartels have morphed into transnational crime syndicates that pose an urgent threat to their security and that of the region. Law enforcement agencies from the border to Maine acknowledge that the traffickers have brought a war once dismissed as a foreign affair to the doorstep of local communities. The trail of slayings, kidnappings and other crimes stretches through at least 195 U.S. cities.

The rapidly escalating problem will probably present the Obama administration with hard choices on how to work with Mexico to combat the cartels and the gun-running, money-laundering and other illicit businesses that nourish them.

So far, the fight has largely been waged by the Calderon administration, which deployed thousands of federal troops and police to 18 states to take on the cartels, some of which have paramilitary forces protecting them and many police officers and politicians in their pockets.

“They know they have a monumental undertaking, but you have to start somewhere,” Michael A. Braun, former assistant director and chief of operations at the Drug Enforcement Administration, said of the Mexican government. “If you don’t, in another five years the cartels will be running Mexico.”

The U.S. answer for fighting the cartels is contained in a package known as the Merida Initiative, named for the Mexican city where it was unveiled by Presidents Calderon and Bush in October 2007. When Congress passed the first installment of the three-year aid package in June, it contained at least 33 programs, giving about $400 million to Mexico for this fiscal year and $65 million for drug-fighting efforts in various Central American and Caribbean countries.

The first tranche of money was delayed until this month, and squabbling and other problems have held up delivery of most direct assistance. A senior State Department official confirmed that Mexico would have to wait more than a year for at least two U.S. transport helicopters and a reconnaissance plane that it says it desperately needs.

Starting from scratch

Some senior U.S. counter-narcotics officials and lawmakers say the U.S.-Mexico relationship has been so polluted for decades by mistrust, neglect and failure to collaborate that the countries must build much of their anti-drug strategy from scratch, even at a time when beheadings and other brutal slayings have become commonplace in Mexico.

They fear the cartels are so strong and well-funded that Mexican government forces will continue to be undertrained, under-equipped and outgunned for years, even with U.S. aid. And they say it could take decades and billions of dollars more to establish the corruption-resistant criminal justice institutions needed to eliminate the cartels and their government benefactors.

“You need a robust internal capacity to identify the cancer, cut it out and move on while checking the margins to make sure it hasn’t spread,” said Braun, who is now managing partner at Spectre Group International, a security consulting firm. “And they have never done that. They never institutionalized law enforcement at any level.”

U.S. authorities remain deeply troubled that corruption in the top echelons of Calderon’s administration could undermine the Merida effort. Some said the recent arrest of Mexico’s former drug czar, Noe Ramirez Mandujano, on suspicion of taking a $450,000 bribe from the cartels showed that Calderon’s effort to root out corruption was working.

Some U.S. officials say they share more information than ever with Mexico. Others are conducting damage assessments after Ramirez’s arrest, and after Mexico revealed that cartel operatives had infiltrated Interpol, the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City and even DEA operations.

Calderon will probably discover more corruption within his government and his administration, but he deserves credit for requesting assistance and battling the cartels since his election two years ago, Braun and other current and former U.S. officials said.

Since it was first unveiled in Merida, the drug plan has been criticized as a confusing patchwork of questionable programs, including military and law enforcement training, high-tech drug-detection scanners and gang-prevention programs.

Then Congress set about making it even more complicated.

Some lawmakers got more money for U.S. counter-narcotics efforts, and others focused on more funding for Central American regional security programs. Many have complained that no one is coordinating the initiative, and that turf battles and confusion reign among the many agencies that have a piece of it.

“You’ve got so many different agencies involved -- who would you even put in charge of it?” said an official with the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Hard feelings

Privately, Mexican officials are furious with Bush for not doing more to investigate and stop the flood of assault weapons coming in from U.S. gun shops and gun shows. One senior Mexican official said the weapons made up about 90% of the cartels’ arsenals.

And Mexico continues to accuse Washington of doing far too little to diminish the southbound flow of billions of dollars in laundered drug proceeds and drug precursor chemicals, even though both are addressed in the initiative.

Washington, particularly the DEA, is so distrustful of Mexican authorities that they share sensitive counter- narcotics intelligence and evidence with only a small group of Mexican officials.

These include a handful of recently installed top aides to Calderon and about 225 Mexican law enforcement officials who have been thoroughly investigated and trained, and who can be continually monitored by the U.S.

They say they have no choice.

“It is very troubling from the standpoint that in order for us to help the government of Mexico help themselves, we’ve got to have the confidence to share very sensitive information without the fear that that information is going to be leaked to the traffickers or to others in a way that could compromise operations and ultimately get people killed,” said Anthony Placido, the DEA’s director of intelligence.

“It would be easy to take the path of least resistance and say they’re all corrupt and we can’t work with them,” Placido said. “But the reality is it is simply much too important not to. They have taken on these traffickers, and now they have to win. And they deserve and need our support.”

The contentiousness surrounding the Merida plan is no surprise to veteran counter-narcotics officials and policymakers. They say it is emblematic of a turbulent relationship between the two countries that has often been defined by bickering, public finger-pointing and an overall atmosphere of mistrust.

For more than two decades, U.S. officials have accused Mexico of ignoring hard evidence that violent homegrown crime syndicates were gaining power and corrupting its police, army and government in a lucrative campaign to flood American streets with cocaine, heroin and other drugs.

Mexican officials said Washington had done little to diminish Americans’ voracious demand for illicit drugs, and had made Mexico vulnerable by cracking down on the Colombian cartels, which then turned to Mexican organizations to move their drugs to the U.S.

And after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, the U.S. turned away from the drug fight, some Mexican officials say.

As the two countries watched and often feuded, the drug groups grew into sophisticated and deadly organized-crime cartels with a global reach, a strong U.S. presence and a stranglehold over many of the Mexican governmental institutions responsible for stopping them.

DEA intelligence now estimates that the cartels are paying hundreds of millions in bribes a year and that they have expanded their operations to Africa, Europe and elsewhere.

Arturo Sarukhan, Mexico’s ambassador to the U.S. and a former counter-narcotics official, cautioned that Merida was only a first step.

He said it wouldn’t be easy to improve cross-border interdiction, intelligence-sharing and an integration of both countries’ counter-narcotics efforts after so much neglect.

“Obviously, the longer you take to address a challenge or disease, the harder it is to root out,” Sarukhan said. “And whoever thinks that the Merida Initiative or the type of cooperation that we have implemented since President Calderon arrived is a silver bullet that will eliminate a decades-old challenge in Mexico is wrong.”

latimes.com /siege Previous coverage of Mexico’s drug war is available online.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.