Owners Seek a Salary Cap for Baseball

Attempting to defray reputed losses and deflate escalating payrolls, baseball’s owners included the concept of a partial salary cap in an eight-point proposal made to the Major League Players Assn. in Monday’s negotiations over a new collective bargaining agreement.

The reaction of Donald Fehr, the union’s executive director, was not unexpected.

Reached by phone at his New York office, Fehr said the owners were attempting to freeze salaries and “emasculate free agency.”

He said there was no way the players would help do the owners’ police work and no chance the proposal would be accepted. He predicted he would receive strike authorization when the union’s executive council meets Thursday in Chicago.

“We waited six months for a first proposal,” Fehr said. “If this is it, they could have done us all a favor and kept it.”

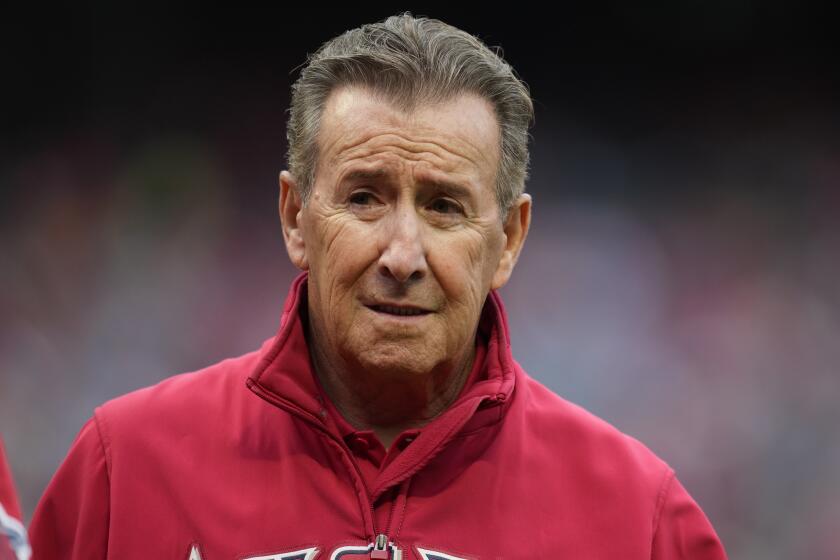

Angel catcher Bob Boone, the National League player representative during the 50-day strike of 1981 and still a member of the executive council, said of the proposal:

“It stinks, but I’ve got nothing more to say. I’ve given enough of Bob Boone to that stuff. Nothing changes, nothing is going to change. Let them (the owners) play their games. I’m not going to get involved.”

Former American League president Lee MacPhail, who represents the owners in the collective bargaining negotiations, said via telephone that the 26 clubs lost $42 million last year and would lose $155 million by 1988.

“We’re not proposing a freeze or attempting to roll back salaries,” he said, “but we feel it’s an absolute necessity that we reverse the trend, that we start addressing the problem.

“We’ve got several clubs in serious trouble. We’ve got to give them time to catch up with their losses.”

A wire service said Monday’s proposal was a “take it or leave it.”

“That’s a misinterpretation,” MacPhail said. “It’s not a take it or leave it. We’re not wedded to any proposal.

“If the players’ association has a better idea we’re willing to listen. In fact, we suggested that we wait and talk about it jointly, but they urged us to go forward.”

MacPhail said the proposal was conceptual and that he was hopeful the owners would be ready to present specifics to the union after its Thursday meeting.

He acknowledged that the chances of the union accepting a salary cap are “probably slim” but that the chances of having a scale accepted were slimmer yet.

The owners’ proposal is based on the average payroll of the 26 clubs. MacPhail estimated that it was about $10 million.

Clubs with a payroll above the average would not be restricted in signing their own players but could not sign free agents and would probably face financial parameters when trading for players.

There would be no restrictions on clubs with a payroll that is less than the average.

The Dodgers, providing $10 million is average, would have been just under it with a 1984 player payroll of $9,179,000, according to Major League Players Assn. figures. The Angels would have been well over it at $13,805,000.

MacPhail called it an attempt to bring order out of chaos. Fehr said the restricted player movement would depress salaries and make the rich clubs richer.

He also dismissed the chaos characterization, citing the union’s preliminary audit of financial records recently provided by the owners on urging of Commissioner Peter Ueberroth.

“Our initial study does not suggest that a dire situation exists,” Fehr said.

Does he accept MacPhail’s contention that the clubs lost $42 million last year.

“No,” he said. “That’s a flat no.”

Fehr was equally negative regarding the owners’ seven other proposals, which were:

--Major improvements in the players’ retirement plan.

--Major improvements in the retirement plan of players already retired.

--An increase in the minimum salary from $40,000 to $60,000.

--Acceptance of the players proposal to abolish the free-agent draft (leaving every free agent eligible to negotiate with all 26 clubs, providing there isn’t a salary cap).

--Acceptance of the players proposal to abolish the professional compensation pool when a Type-A free agent is signed.

--Protection for the unfunded $250 million in deferred payments now owed by the 26 clubs.

--Adoption of an improved waiver system, an increase in meal money and spring living expenses and an increase in the players playoff and World Series pool.

“Substantially,” MacPhail said, “we’re giving the players everything they’ve asked for.”

Fehr disagreed, saying the proposals were devoid of specifics and contained no mention of the players’ demand for a one-third share of the six-year, $1-billion-plus national TV package signed by baseball last year and a one-third share of the extra $9 million baseball will receive from TV for increasing the playoffs to seven games.

“What’s a major improvement?” Fehr asked, alluding to the wording of the owners’ proposals. “One dollar? Ten dollars? How are we to know how all of this is going to be done? Are we ever going to get specifics?”

The collective bargaining agreement that was signed after the strike in 1981 expired Dec. 31, 1984. The lack of progress in the new negotiations has created speculation that another strike is certain.

Fehr said the players are furious at being put through the same wringer as in 1981, being forced to cope with the same absence of negotiation. He said the players have discussed the possibility of a strike and that it could come any time after the end of June. He said a boycott of the July 16 All-Star game at Minneapolis is a possibility.

Angel third baseman Doug DeCinces, also a member of the union’s executive council, said it was an unfortunate absurdity to have to wait until May 20 to begin negotiations.

“What’s more unfortunate,” he said, “is that we have a long ways to go (before arriving at a settlement) and we’ll reach a point where one side will hold a gun at the other’s head.

“I don’t want that. I don’t want to see the game hurt. I’d be the first to go to bat for baseball if it was proven to me that it was in financial jeopardy, but I haven’t seen figures that would justify changing the structure as the owners are proposing.

“They’ve studied long and hard and come up with something that would obliterate free agency and rising salaries while doing nothing at all to help the poorer clubs, and that’s all we ever hear about. It’s (the proposed salary cap) so bizarre, my reaction was, ‘what’s happened to the free enterprise system?”’

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.